AN IMPROVISED TRUTH

Los Angeles-based Impro Theatre opens a run of Jane Austen: UnScripted on Valentine’s Day at the Pasadena Playhouse’s Carrie Hamilton Theatre. Their most recent L.A. performance at the Odyssey Theatre, inspired by another giant of international literature, may offer a parallel idea of what to expect in Pasadena:

The set awaits, a pleasant throw of rugs and stately furniture, enough to suggest a drawing room at a country estate, a datcha, or a well-appointed Moscow apartment. The players come out and line up, four men and three women; they wear lovely, nonspecific turn-of-the-century Russian middle-class costumes. They take a recommendation from the audience on the view out the window: “Serfs working in a field!” And with no further preparation, they announce the beginning of act one of this incarnation of Chekhov: UnScripted.

Although it might be the production truest to the cruel comedy and quiet horror of genuine Russian despair that most of us will ever see, this UnScripted presentation by Impro Theatre wasn’t written by Anton Chekhov. This is a full-length improvised literature in the style of Chekhov, less an exercise at this point than a delicate and, at its best, breathtaking new form. This production exists inside a movement that could revitalize the widely-heralded-as-dying art of theater, but very possibly will not, because it cannot be performed by dilettantes. This rigorous activity requires investment to attain mastery, a full-body immersion in craft and study, and who bothers anymore?

Although it might be the production truest to the cruel comedy and quiet horror of genuine Russian despair that most of us will ever see, this UnScripted presentation by Impro Theatre wasn’t written by Anton Chekhov. This is a full-length improvised literature in the style of Chekhov, less an exercise at this point than a delicate and, at its best, breathtaking new form. This production exists inside a movement that could revitalize the widely-heralded-as-dying art of theater, but very possibly will not, because it cannot be performed by dilettantes. This rigorous activity requires investment to attain mastery, a full-body immersion in craft and study, and who bothers anymore?

Lights up: a man stands staring through his front windows. His wife enters, calls him by his Christian and patronymic names (everybody in the show gets two names), and asks, “Are they still out there?” He answers that they are. His daughter enters and looks out, too, says “I’ll take them some food,” and goes. Their houseguest, a doctor, enters laughing and asks, “They’re still out there, then? When will you tell them you can’t afford to pay them anymore?”

The doctor exchanges a glance with the estate owner’s wife and commences to flirt. The preoccupied man remains downstage, pacing pensively. A bent old servant enters and asks whether he will be let go with the rest of the serfs, and he is reassured that his position, at least, is safe.

The modern decline in box-office receipts has spurred theater impresarios to spectacle, to pandering, to imitations of other forms such as film and television. Improvisational theater is such a surprising concept that it just might stem the tide of indifference.

The modern decline in box-office receipts has spurred theater impresarios to spectacle, to pandering, to imitations of other forms such as film and television. Improvisational theater is such a surprising concept that it just might stem the tide of indifference.

On the oft-heard complaint from audience members – “I don’t believe you’re making it up” – Impro Theatre artistic director Dan O’Connor ruminates, “Whether you’ve been doing it a year or twenty years, it’s a compliment. The blue-haired little old ladies enjoy it – they don’t know what they’ve seen, but they have a good time.” Some well-regarded critics have pronounced in Impro reviews that certain show elements are obviously planned, and Impro has had to disabuse them of their presumption by offering repeat viewings.

Flattering, maybe, but problematic too. This is the immediate issue facing full-length improvisers: how to explain and popularize the hard-to-believe magic they make. Even after you’ve seen it, you might not credit the work being done, especially if your experience of improv is limited to brief exercises in finding the joke. And if your idea of a play is limited to a piece already written, performed by actors who have rehearsed their performances for weeks before you get to see them, then two hours’ spontaneous creation of a single drama, with complex characters in multi-dimensional relationships, weaving a sound thematic structure and logical plot development from the ether, seems preposterous. The first train that ran over 50 miles an hour was predicted by British physicians to kill all its passengers by removing the air from their lungs. It just didn’t seem possible that people could go that fast.

The oblivious estate owner tries to play matchmaker between his idle, unmarried cousin and the doctor; the girl is underwhelmed by the prospect, and the doctor, while vain enough to enjoy the idea of a liaison, keeps his mind on his hostess.

First and last, play-length improvisation doesn’t come from the blue; the undertaking requires enormous preparation. Besides Chekhov, Impro Theatre invents two-act shows in the style of Tennessee Williams, William Shakespeare, Stephen Sondheim (think about the requirements of that one), and The Twilight Zone, among others. Each of these projects begins with academic study. The directors prepare a mountain of material on authorial motifs, themes, structural tendencies, language, and on how an improviser can best insert himself into that writer’s world. They organize rehearsal exercises that instill the performers with a comprehension of the parameters associated with a given author or style: styles of name, movement, mood.

First and last, play-length improvisation doesn’t come from the blue; the undertaking requires enormous preparation. Besides Chekhov, Impro Theatre invents two-act shows in the style of Tennessee Williams, William Shakespeare, Stephen Sondheim (think about the requirements of that one), and The Twilight Zone, among others. Each of these projects begins with academic study. The directors prepare a mountain of material on authorial motifs, themes, structural tendencies, language, and on how an improviser can best insert himself into that writer’s world. They organize rehearsal exercises that instill the performers with a comprehension of the parameters associated with a given author or style: styles of name, movement, mood.

But the work starts years before any of that. A student of improvisation begins like any other with a certain amount of native talent. Improv classes may quickly improve her acting, in her ability to read and react to new circumstances, but her skill at extemporaneous storytelling may gestate over a period best measured in decades. Some of the members of the Impro Theatre have been improvising for thirty years – a few have worked together for twenty – and the difference between their work and that of their less seasoned fellows can be stark.

Another houseguest enters, an artist, and presents some sketches he has made of the lady of the house. These drawings portray the lady in her nightgown, and her husband mildly objects to the revelation that his wife is accompanied by his guest on her nightly rambles about the estate. Neither does the doctor appreciate this news. The room grows tense, but the daughter enters on an errand and distracts the conversation onto the value of industry to the formation of a soul. Her effervescence depresses her father, but the doctor smirks with condescending approval.

If recognition of the long-form achievement is a big challenge, a bigger one might be that slow growth factor. “Noobs” of perhaps ten or twelve years’ experience can still get into barely-integrated onstage arguments over one’s denial of the other’s reality (“I thought I was standing at the side of the road but if you say so, I guess I was driving the car”). Of course covering the gaffe is necessary, but dual marks of inexperience show: that one of the performers didn’t pay enough attention to the unfurling circumstance, and that the other showed exasperation during his damage control. More experienced improvisers tend to make a joke and a motif of such happy accidents; this is possible because the occasions are rare. The more experienced performer is unlikely to be as inattentive as the relative rookie. This thing takes practice.

If recognition of the long-form achievement is a big challenge, a bigger one might be that slow growth factor. “Noobs” of perhaps ten or twelve years’ experience can still get into barely-integrated onstage arguments over one’s denial of the other’s reality (“I thought I was standing at the side of the road but if you say so, I guess I was driving the car”). Of course covering the gaffe is necessary, but dual marks of inexperience show: that one of the performers didn’t pay enough attention to the unfurling circumstance, and that the other showed exasperation during his damage control. More experienced improvisers tend to make a joke and a motif of such happy accidents; this is possible because the occasions are rare. The more experienced performer is unlikely to be as inattentive as the relative rookie. This thing takes practice.

An under-confident player also is likely to run through nervous patterns like buttoning and unbuttoning his jacket four times in a minute, so that it’s impossible to think of him as a character rather than an unready performer. And these are, all of them, very good actors. In a straight play these idiosyncrasies would not appear. The fact is that it takes so much more work to be good at this than to be good at mere acting, or mere improvisation. Twelve years is an awfully long time to commit to a craft and still be capable of a major lapse and for that to be par for the process  of development. Such nerves are completely understandable: if you think stand-up takes guts, and acting in front of a roomful of people is intimidating, try carrying a play when you don’t know where it’s going.

of development. Such nerves are completely understandable: if you think stand-up takes guts, and acting in front of a roomful of people is intimidating, try carrying a play when you don’t know where it’s going.

But, again, what makes this movement a longshot to revitalize the sagging world of live theater is that what these performers do cannot easily be emulated. Any kid who can memorize lines may throw together a Shakespeare company; to mount long-form improvisation requires more energy and talent, and vastly more time, than most actors will ever be willing to devote.

The doctor complains that the artist has failed, in his portrait, to capture the lady’s eyes. The two rivals clearly have more to fear from one another than from the husband, who is increasingly distracted by the problem of his failure at agriculture and at life. His wife offers the company a tea, but discovers that there’s no food in the house: her daughter has given it all to the serfs, who stubbornly cling to their traditional roles and privileges despite evidence that their time has passed.

What Impro Theatre does is inherently theatrical. Each show is so naturally ephemeral that it’s a one-night-only affair even in a long run. The form’s appeal largely hinges on the live-without-a-net thrill of watching a dangerous enterprise that could easily fail. Watching Impro work, one never escapes the nail-biting exhilaration of fear and hope – that someone won’t know what to say next; that his partner will turn a faltering moment into a lyric.

What Impro Theatre does is inherently theatrical. Each show is so naturally ephemeral that it’s a one-night-only affair even in a long run. The form’s appeal largely hinges on the live-without-a-net thrill of watching a dangerous enterprise that could easily fail. Watching Impro work, one never escapes the nail-biting exhilaration of fear and hope – that someone won’t know what to say next; that his partner will turn a faltering moment into a lyric.

The old servant enters, holding a nail he has found. He quietly tests the furniture for stability, piece by piece, moving behind the downstage action and muttering poetically about the state of disrepair in the house and the world generally.

The doctor gets his hostess alone; their flirtation has the desperate flavor of doom. The artist moons in frustration. The visiting cousin enters, excited to have found a great litter of nails all about the place; she plans to use them in the creation of an art piece to inspire the serfs. The estate owner would rather not encourage the serfs to stay, but he can’t deny his cousin’s generosity and activity. The artist gets his hostess alone and they make plans to run away together. The lady agrees, with evident reservations.

A great crash is heard offstage: the old servant has fallen through the upstairs floor, which has collapsed due to the missing nails and overall entropy. This marks the end of Act One.

O’Connor begins a mid-run rehearsal for Chekhov: UnScripted with a general critique of the previous weekend’s shows. He exhorts his people to keep digging deeper. Some of what he says sounds like any director at any rehearsal: “We could still want things more, have more at stake. And [an actor] is still saying Mos-cow. It’s Mos-coe.”

O’Connor begins a mid-run rehearsal for Chekhov: UnScripted with a general critique of the previous weekend’s shows. He exhorts his people to keep digging deeper. Some of what he says sounds like any director at any rehearsal: “We could still want things more, have more at stake. And [an actor] is still saying Mos-cow. It’s Mos-coe.”

Some of the focus, though, is purely improv. A performer is concerned that because a recent show manifested two unmarried girls, it was drifting away from Chekhov into Austenian waters. “I don’t think so,” O’Connor says; “they just have to want something – to get married, to escape. Of course I’ll have unrequited love in Chekhov, too.”

Co-founder and associate artistic director Brian Lohmann interjects: “People look forward and backward in Chekhov.” O’Connor agrees, mentioning that key Chekhovian emotion: resignation. Lohmann asks, “Is there anything showing up too much in the Chekhov? Is there a dead horse we’re beating?”

O’Connor says, “We’ve had two poets and one actress halfway through the run; we don’t always need a doctor.”

Jo McGinley, one-fourth of two married couples in the company (her husband is Steven Kearin; O’Connor is married to Edi Patterson), asks: “Have we repeated themes?”

O’Connor considers this. “We haven’t had a lot of escapist wants, which is good. I would love it if we didn’t reference a cherry orchard the rest of the run. Irina and Masha and Olga all ended up in the same play this week. Luckily they weren’t sisters, but it gives the old ladies too much grist for the mill.”

He continues, “Names names names. Get those names out early and repeat ’˜em if you can. I know we talked a lot last week about punctuation; a couple of those shows I think we could be ending a little better. The Ferris Wheel on fire was a great bit, because everybody wanted to ride on the Ferris Wheel and nobody could. But the cheesemakers out in a field, we were a little too much in love with looking out at a field. A note we can keep for the whole run: say less. Because people make an offer and justify the offer rather than see what someone else will do with it. We’ve had some excellent vodka and samovar work; but that moment done silently is more arresting than me telling her how I’m feeling. How can I say it without saying it? Remember, it’s constantly covering with Chekhov. And even though we are wearing costumes, we need to overaccept those costumes. If you’re always pulling up your skirt, I want to do an exercise about long strides and throwing that skirt out longer.”

He continues, “Names names names. Get those names out early and repeat ’˜em if you can. I know we talked a lot last week about punctuation; a couple of those shows I think we could be ending a little better. The Ferris Wheel on fire was a great bit, because everybody wanted to ride on the Ferris Wheel and nobody could. But the cheesemakers out in a field, we were a little too much in love with looking out at a field. A note we can keep for the whole run: say less. Because people make an offer and justify the offer rather than see what someone else will do with it. We’ve had some excellent vodka and samovar work; but that moment done silently is more arresting than me telling her how I’m feeling. How can I say it without saying it? Remember, it’s constantly covering with Chekhov. And even though we are wearing costumes, we need to overaccept those costumes. If you’re always pulling up your skirt, I want to do an exercise about long strides and throwing that skirt out longer.”

O’Connor leads an exercise in which three players are “dressed” in imaginary costumes and given relationships (he’s in love with her, but she loves the other, who’s only in love with his past). Afterward, O’Connor gives notes: when a character asks for a belt, offering him taffy is a little too broad for our purposes. Rather than just having an argument, make it about the history, about the story.

An actor has a question about relationships, and being unsure of her character onstage. O’Connor says, “That tentativeness? If you feel that, just say ’˜my darling,’ or something definitive, and go forward.” The actor responds, “But when I’m the one who calls it, I worry ’˜what if I missed something?’ Is there a thing I didn’t hear, and I’m going to be the one who screws it up.”

Floyd Van Buskirk interjects: “I don’t have to know why. I can just be worried about something and figure out why in the second act.”

Lohmann nods, mentioning a basic mantra of improvisational creation: “It’s yes, and, because. The because could come in act 3.”

At the top of Act Two, at the audience’s suggestion, the doctor and the artist stand onstage together. They accuse each other of interference in their seductions of the same woman. Their host enters, and he and the doctor discuss the serfs’ recent departure: it seems likely that they have taken the old servant’s accident as a bad omen. The doctor describes the event as a measure of progress, but the estate owner can only see in it the deterioration of his own life and purpose. His daughter, lacking an outlet for her benevolence in the serfs’ absence, devotes herself to caring for the injured servant.

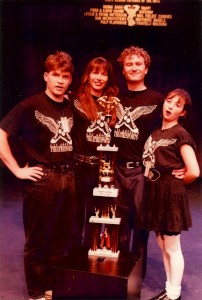

The Impro pedigree includes great names of improv, and nobody in the present company goes back further than Floyd Van Buskirk. In the early 1980s, he was doing Chicago-style improv with Roberta Maguire’s company None of the Above, practicing what he calls “Second City type stuff.” None of the Above brought the seminal English improvisational director Keith Johnstone down from Canada to teach some workshops. For Van Buskirk as for thousands of others, Johnstone’s observations on status (which determines how acting partners play relationships onstage) opened up a new world. Within a year Van Buskirk had founded Seattle Theatresports as its first artistic director, playing in tournaments against players from Calgary and Vancouver and training improvisers to expand their moments by playing regularly and passionately. One of his students, Rebecca Stockley, headed south to help start Bay Area Theatresports, where she taught founding members O’Connor and Lohmann. O’Connor in turn eventually came down and started LA Theatresports with the late Ellen Idelson. Van Buskirk joined the Los Angeles franchise in 2000 as education director, becoming artistic director from 2002-2004, when the company changed its name to Impro Theatre.

The Impro pedigree includes great names of improv, and nobody in the present company goes back further than Floyd Van Buskirk. In the early 1980s, he was doing Chicago-style improv with Roberta Maguire’s company None of the Above, practicing what he calls “Second City type stuff.” None of the Above brought the seminal English improvisational director Keith Johnstone down from Canada to teach some workshops. For Van Buskirk as for thousands of others, Johnstone’s observations on status (which determines how acting partners play relationships onstage) opened up a new world. Within a year Van Buskirk had founded Seattle Theatresports as its first artistic director, playing in tournaments against players from Calgary and Vancouver and training improvisers to expand their moments by playing regularly and passionately. One of his students, Rebecca Stockley, headed south to help start Bay Area Theatresports, where she taught founding members O’Connor and Lohmann. O’Connor in turn eventually came down and started LA Theatresports with the late Ellen Idelson. Van Buskirk joined the Los Angeles franchise in 2000 as education director, becoming artistic director from 2002-2004, when the company changed its name to Impro Theatre.

The host, the doctor, and the artist engage in a drinking bout, their uncomfortable dynamic lending a hideous tone. At one point the doctor asks the artist if he remembers an old drinking song from student days; the doctor sings a bar or two and the artist recognizes the tune but clearly would rather not join in camaraderie with this man. Their host rather mean-spiritedly encourages them to finish the song, and together, they stagger into a tune, each taking a verse and finally finishing on a common note, singing lyrics identical in intent and only slightly different in vocabulary, as if one of them is too drunk to remember the exact words.

The audience lags a shocked moment before bursting into scene-stopping applause.

Though it had been mounting Shakespeare UnScripted since 1999, in 2006 the company abandoned all other performance styles to pursue the UnScripted rep shows full-time; membership winnowed at the concept. Van Buskirk admits that “since there wasn’t a lot of stage time we lost a lot of people.” And not every good actor is (or wants to be) competent at making up dialogue and story. Lohmann says, “Saying yes is frightening. At first you say no because you don’t want your subconscious to be ridiculed.” But he also reminds me that a driving rule of improvisation, contrary to popular conception, is not “never say no” but “don’t kill the other person’s idea.”

Though it had been mounting Shakespeare UnScripted since 1999, in 2006 the company abandoned all other performance styles to pursue the UnScripted rep shows full-time; membership winnowed at the concept. Van Buskirk admits that “since there wasn’t a lot of stage time we lost a lot of people.” And not every good actor is (or wants to be) competent at making up dialogue and story. Lohmann says, “Saying yes is frightening. At first you say no because you don’t want your subconscious to be ridiculed.” But he also reminds me that a driving rule of improvisation, contrary to popular conception, is not “never say no” but “don’t kill the other person’s idea.”

The injured servant limps into the drawing room, fluttered over by the almost perversely solicitous daughter. After depositing him in a chair, she exits to retrieve some further element of comfort. In her absence, the servant announces that he is leaving the estate to follow the other serfs. Dismayed, his employer asks why, and the servant admits that the daughter’s attentions are strangling him.

Asked what draws a person to such a naked and risky form, Lohmann answers: “Everybody in the company has a rebellious streak and a love of freedom. It’s astonishingly freeing. And we like that because if you don’t have a script you can’t phone it in.” Van Buskirk says, “I would have stopped (doing improv) years ago if we hadn’t started doing long-form UnScripted stuff.”

The visiting cousin banters with the doctor on the vagaries of bourgeois motivations and desires; he suggests that even those comfortably situated in life have their problems. She agrees, overlooking the drawing room with an ennui bordering on contempt. The doctor idly asks her if she doesn’t have any problems at the moment, and she viciously spits, “This room has too many rugs!”

In describing the nature of their work, Lohmann and Van Buskirk talk a lot about their fascination with the collective. “How does collectivism show up on stage?” Lohmann asks. “How does that one mind work? Well, early on, we can not kill each other’s ideas, we can play consistent characters, play the wants. You can’t leave anyone behind; no storyteller is going to feel like they’ve satisfied their audience if they’ve hung a character out to dry. When someone floats an idea onstage that the rest of the company allows to fly, or doesn’t, you have to trust the group and say I’m in one seat at this table.”

In describing the nature of their work, Lohmann and Van Buskirk talk a lot about their fascination with the collective. “How does collectivism show up on stage?” Lohmann asks. “How does that one mind work? Well, early on, we can not kill each other’s ideas, we can play consistent characters, play the wants. You can’t leave anyone behind; no storyteller is going to feel like they’ve satisfied their audience if they’ve hung a character out to dry. When someone floats an idea onstage that the rest of the company allows to fly, or doesn’t, you have to trust the group and say I’m in one seat at this table.”

“Group mind always begins at a lower intellect than any individual member,” he continues. “As we develop communal synapses, the group mind gets smarter. I think it’s smarter than we are now. We decided we didn’t want to play in comedy clubs anymore. We became a theater company. Now we play for theatergoing audiences because we’re doing theater.”

Van Buskirk adds, “Actors who work with a script try to make it look improvised. We’re trying to make improvised work look scripted.”

The wife and the artist meet surreptitiously, carrying suitcases and planning their escape; in his excitement, the artist shows her his latest portrait. She appears stricken and suddenly abandons her plans with the artist, murmuring that her husband used to draw her this way. The doctor observes this interaction and steers the husband into the room, alone with his wife. The unmarried cousin, noting the doctor’s magnanimity, finds herself attracted to him; and this stroking of his ego quietly but definitely makes him responsive to her attention.

O’Connor says of the latest production, “This time we brought in a couple of actors without much experience at improv, which was very grounding for the rest of us – and it was nice to have an actor who’s more interested in character and not going to be a Chatty Cathy. But even during the run we rehearse once a week to make sure we’re not repeating beats or characters.”

O’Connor says of the latest production, “This time we brought in a couple of actors without much experience at improv, which was very grounding for the rest of us – and it was nice to have an actor who’s more interested in character and not going to be a Chatty Cathy. But even during the run we rehearse once a week to make sure we’re not repeating beats or characters.”

Improv superstars like Michael McShane make occasional guest appearances in some Impro shows, and there’s no question that what Impro does is a galvanizing experience for almost anyone who sees it. But given the practical difficulties involved in nurturing a reliable performer, and in cultivating an audience for a new form, is long-form improvisation sustainable, and capable of developing into a large movement?

The estate owner’s wife observes him for a long moment before asking what he’s holding, and he shows it to her: it’s a new portrait that he has drawn of her. “You found my eyes,” she says, glowing like a girl awakening from fever.

Nick Massouh, head of the Impro school, does not agree with me that it takes all that long to develop the next generation of talent. In order to concentrate more on an ensemble dynamic, the school has stopped teaching in workshop levels, as do other improv schools such as those at The Groundlings and Second City. Impro currently has about 50 students, and sometimes as many as 100; many of them stick around for years, undeterred by the learning curve. It’s also recently started the Impro LAB, a student performance group that will start putting up its own shows in April.

Massouh asserts, “The school is not just a feeder for the company,” and that each student has his or her own agenda for attending. Some want to overcome social anxiety; some wish to be more aware of their own impact on their environment.

Massouh asserts, “The school is not just a feeder for the company,” and that each student has his or her own agenda for attending. Some want to overcome social anxiety; some wish to be more aware of their own impact on their environment.

But isn’t this lack of a large pool of devotees from which to draw just one more obstacle to sustainability? O’Connor mentions that some Impro students have already made their own way, and he points across Vermont Avenue from the Impro offices to the Skylight Theatre, where some of those students are running an improvised soap opera called The Rich and the Reckless.

And here beats the heart of the matter. Those former students are currently investigating their own passion for this daunting and exacting exercise, and in a few years that company will have done one of two things. It will have disbanded into individual agendas other than monkish devotion to a pursuit with questionable prospects, or it will have joined the gradually swelling ranks of theaters around the country – Austin has its share, and San Francisco and Boston and New York – that intend to demand more of themselves as they challenge the marketplace by offering something new.

The estate owner assures his faithful servant that his daughter will find another focus for her compassion, and soon she enters carrying a broken-winged bird she intends to nurse back to health.

The servant watches the husband’s attention reposition itself from his dismal self-loathing onto his once-beloved wife, and the servant offers a pithy aphorism or two on the nature of happiness. The artist wanders out to follow the serfs on their odyssey to a better life, determined to draw and paint their struggle against disappointment.

And the husband (speaking largely to himself) asks his wife whether she is happy, or at this stage of life even capable of happiness. She gazes at him, pondering the question, then away from him. The doctor and the unmarried cousin too exchange a questioning look. The lights fade. The audience is already applauding, many on their feet.

Van Buskirk knows where he wants the Impro train to go: “I’d like to see published plays that were created in one night. We might create two that we could publish, in two years.”

Van Buskirk knows where he wants the Impro train to go: “I’d like to see published plays that were created in one night. We might create two that we could publish, in two years.”

Lohmann says, “End game? We do a run in an Equity house.”

Impro has played fancy houses like The Broad Stage, and various prime venues in New York and Canada, but how long will it go on like this? The labor required seems impossible to continue indefinitely.

Van Buskirk hesitates not at all: “We do it because we love it. Sustainable? We did Theatresports in Seattle until they showed up. It only took about eight years. In L.A., at the beginning of Impro Theatre, we couldn’t get a house; we’d go out of town, yes, people came, but not here… but now even on an off night we’re getting 50, 60 heads. Being able to bring acting skill to this improv – I can go out there and I can be in love, or I can be in pain. It’s sustainable for us because it’s never good enough.”

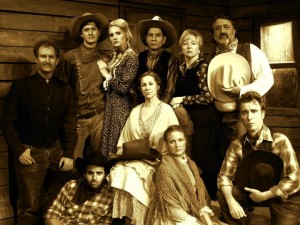

production photos by Will Adashek, Enci and Blake Gardner

Jane Austen: UnScripted

Impro Theatre at The Carrie Hamilton Theatre in Pasadena

opens February 14, 2013; scheduled to end April 14, 2013

for tickets, call (626) 356-7529 or visit http://www.PasadenaPlayhouse.org

Link to Stage and Cinema’s review of UnScripted Rep

Link to (Old) Stage and Cinema’s review of Shakespeare UnScripted