THREADBARE

In the 1950s, dissident South African Can Themba wrote a short story called “The Suit,” describing a cuckold’s response to his wife’s infidelity – specifically his insistence that her lover’s clothes remain in their home as an honored guest. It was perhaps too blunt a metaphor for the psychology of living without self-determination; for this and other writings, apartheid policies labeled the author an undesirable. Themba’s works became largely unavailable in his home country. He moved to Swaziland to teach and drink, dying a disappointed exile in the late 1960s.

Mothobi Mutloatse and Barney Simon staged the story as The Suit at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre in 1993, and in 1999 Peter Brook’s Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord adapted the story and play from their original English into French. As Le Costume, it toured the world. Now, in collaboration with co-adaptor Marie-Hélène Estienne and composer Franck Krawzcyk, Brook has retuned the project back into English, colored it with new music, and sent it once again out among us. The Suit is currently on view at the Freud Playhouse.

Mothobi Mutloatse and Barney Simon staged the story as The Suit at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre in 1993, and in 1999 Peter Brook’s Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord adapted the story and play from their original English into French. As Le Costume, it toured the world. Now, in collaboration with co-adaptor Marie-Hélène Estienne and composer Franck Krawzcyk, Brook has retuned the project back into English, colored it with new music, and sent it once again out among us. The Suit is currently on view at the Freud Playhouse.

I describe it in this manner because the thing is less play than objet d’art. It features very little in the way of drama, and it is quite as much music as story. What gripping moments it contains, and there are a couple, are as often about the collective guilt of the audience as they are illustrations of the narrative. There are actors, and they act; there are musicians, and they play. Everybody sings. It’s the briefest sketch of life, and I got little from these 75 slight minutes. Whatever changes may have taken place over the fifteen years since Brook first presented the piece, as it is now, the gossamer plot is as oblique as the director’s ambitions are obscure.

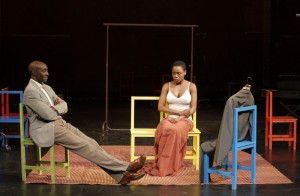

A performer says in an introductory soliloquy, “The story I’m going to tell couldn’t have happened anywhere except in countries like South Africa, which lived under the iron fist of oppression.” If “iron fist of oppression” sounds like bad writing, and it should, at least it’s one of the only lines in the play that Brook claims as his own. His directorial stamp here is less overt, but for me it is not less tedious. A classically simple table-and-chairs set is pushed about in a desultory fashion, lines delivered matter-of-factly. Nothing really builds, and the climax is not only predictable but predictably unsatisfying. The show has no flame and few sparks. The source material is so thin that the adaptors pad it out with urban landscape and local color from Themba’s memoirs and journalism; also, with a few too many songs. If these do not exactly lard the play, neither do they give it wings.

A performer says in an introductory soliloquy, “The story I’m going to tell couldn’t have happened anywhere except in countries like South Africa, which lived under the iron fist of oppression.” If “iron fist of oppression” sounds like bad writing, and it should, at least it’s one of the only lines in the play that Brook claims as his own. His directorial stamp here is less overt, but for me it is not less tedious. A classically simple table-and-chairs set is pushed about in a desultory fashion, lines delivered matter-of-factly. Nothing really builds, and the climax is not only predictable but predictably unsatisfying. The show has no flame and few sparks. The source material is so thin that the adaptors pad it out with urban landscape and local color from Themba’s memoirs and journalism; also, with a few too many songs. If these do not exactly lard the play, neither do they give it wings.

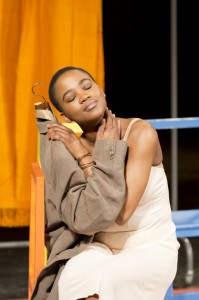

Brook’s early quest for spontaneity (outlined in books like the forty-five-year-old, still-required-reading The Empty Space) has largely been detoured away from, by both the director and two-thirds of his cast. As the adulterous wife, Nonhlanhla Kheswa marks time onstage, not living moments as much as predicting and awaiting them. She is very nice to look at, and quite passably sings songs by Miriam Makeba and others, but while she may have been discovered for the stage by her director, he has not yet made of her a truthful actress. In several swing roles, Jordan Barbour has fun playing women but saws the air and indicates his way through his male roles. (His director, oddly, stuffs the Abel Meeropol lynching-paean “Strange Fruit” into Barbour’s mouth – and while his face is still rife with what feels like disingenuous emotion, his voice soars; it’s the show’s only truly arresting moment, even though the whole time one wonders what this tune’s doing in a South African township.)

Brook’s early quest for spontaneity (outlined in books like the forty-five-year-old, still-required-reading The Empty Space) has largely been detoured away from, by both the director and two-thirds of his cast. As the adulterous wife, Nonhlanhla Kheswa marks time onstage, not living moments as much as predicting and awaiting them. She is very nice to look at, and quite passably sings songs by Miriam Makeba and others, but while she may have been discovered for the stage by her director, he has not yet made of her a truthful actress. In several swing roles, Jordan Barbour has fun playing women but saws the air and indicates his way through his male roles. (His director, oddly, stuffs the Abel Meeropol lynching-paean “Strange Fruit” into Barbour’s mouth – and while his face is still rife with what feels like disingenuous emotion, his voice soars; it’s the show’s only truly arresting moment, even though the whole time one wonders what this tune’s doing in a South African township.)

These are not the performances I was expecting of a Peter Brook show, and I would guess that I was looking for something the director didn’t intend to give…except that, as the bewildered cuckold, Ivanno Jeremiah supplies the fresh, vital, moment-to-moment life I wanted from everybody else. Unfortunately, the play shoves him offstage just as his character ought to come up with an activity to further the action.

These are not the performances I was expecting of a Peter Brook show, and I would guess that I was looking for something the director didn’t intend to give…except that, as the bewildered cuckold, Ivanno Jeremiah supplies the fresh, vital, moment-to-moment life I wanted from everybody else. Unfortunately, the play shoves him offstage just as his character ought to come up with an activity to further the action.

Even the good, versatile band (Arthur Astier, guitar; Mark Christine, piano; Mark Kavuma, trumpet) mostly feels muted, as if we’re hearing them through a wall, and getting only half their available energy. As with the acting, this would seem more like a choice if it were consistent. But during a couple of party scenes, the band and the cast really let go; during one party, three or four audience members are coaxed onstage to join the fun. The gesture would work if everyone in the house could go to that party, or if these parties existed at all except as an obvious set-up to the coming reversals; but our selected avatars are always going to be too stage-shy and awkward to allow us much vicarious experience, and for the rest of us, our not being on the stage reminds us how separate we are from the characters. If, as my theater companion suggested afterward, the whole show were a chamber piece, a small show for small audiences, it would surely feel more present. But it would still not make a lot of dramatic sense, and it would still make me long for a little less restraint in my brash political theater.

photos by Pascal Victor and Johan Persson

photos by Pascal Victor and Johan Persson

The Suit

Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord

presented by CAP/UCLA

Freud Playhouse at UCLA

scheduled to end on April 19, 2014

for tickets, call 310-825-2101

or visit www.cap.ucla.edu

U.S. tour continues through May 24, 2014

for more info, visit www.bouffesdunord.com