LBJ’S RELEVANCY

After premiering at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2012 and moving to American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Robert Schenkkan’s All the Way became the hot ticket on Broadway last year. Positive reviews and the presence of Bryan Cranston (from the AMC drama Breaking Bad) in the lead role of Lyndon B. Johnson had the play break attendance records for an eight-week run. Not only did it sweep the major awards for best play and actor, but its epic political scope and canvas made it one of the most talked about plays outside theater circles in years.

But it all began in Ashland, OR, and The Great Society’”the second part of Schenkkan’s intense probing of the towering, tragic, and troubled LBJ’s presidency’”allows audiences the chance to see the actor who first imbued life into the man:  Jack Willis.

Jack Willis.

Willis, who looks and sounds far more like LBJ than Cranston (but even more like a slimmed-down John Goodman), delivers a monumental performance in his second turn as America’s 36th President. The play, directed by Bill Rauch, has a longer time span than All The Way, covering the aftermath of his November, 1964 election to his announcement in March, 1968 that he would not run for re-election.

More time means more ground to cover than its predecessor, which spanned 11 months. The Vietnam War, riots in urban cities, civil rights demonstrations, and LBJ’s efforts to get his ambitious legislative proposals approved by Congress are just a few of the major issues encountered. The result is a 1960’s history buff’s dream realized, but it does tend to sprawl and lag at points.

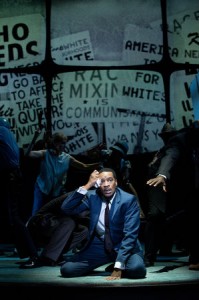

Another major difference is that while LBJ was the central figure in the first play, this one sees Martin Luther King (Kenajuan Bentley) receive nearly as much focus, with supporting characters Robert Kennedy (Danforth Comins) and Richard J. Daley (Denis Arndt) also pulling a great deal of attention from the most fascinating part of this story: Johnson himself. That feels particularly acute in the second act, which gets mired in a long pissing match between King and Daly over equal housing demonstrations in Chicago; as such, it fails to build on the explosive tension of the first act.

Another major difference is that while LBJ was the central figure in the first play, this one sees Martin Luther King (Kenajuan Bentley) receive nearly as much focus, with supporting characters Robert Kennedy (Danforth Comins) and Richard J. Daley (Denis Arndt) also pulling a great deal of attention from the most fascinating part of this story: Johnson himself. That feels particularly acute in the second act, which gets mired in a long pissing match between King and Daly over equal housing demonstrations in Chicago; as such, it fails to build on the explosive tension of the first act.

But it remains a compelling and absorbing piece of theater, and epically tragic, with LBJ beginning his presidency with wild grandiose dreams and ending it one of the more reviled men to ever sit in the Oval Office. And while battles over civil rights are obviously important in the play, there’s no questioning that the quagmire of Vietnam is the Damoclean Sword that eventually drops and eviscerates his presidency.

As the play progresses, Willis’s Johnson becomes more arrogant, yet also conflicted. As his popularity plummets and body counts and torched neighborhoods increase to dizzying numbers, he is more determined than ever to maintain his grip on a power that he never seemed to truly feel was his to begin with, since his was a most accidental presidency. He is relentlessly determined to end the spiraling war, which he initially sees as a minor distraction to his domestic policies, and even as he begins authorizing tens of thousands of new troops, he’s blindly convinced a victory is impending. But though he blusters, manipulates, and strong-arms in his efforts to govern, there are more intimate moments, particularly with his wife and daughter, where the real man emerges and it’s clear how agonizing it is for him to wear this crown.

As the play progresses, Willis’s Johnson becomes more arrogant, yet also conflicted. As his popularity plummets and body counts and torched neighborhoods increase to dizzying numbers, he is more determined than ever to maintain his grip on a power that he never seemed to truly feel was his to begin with, since his was a most accidental presidency. He is relentlessly determined to end the spiraling war, which he initially sees as a minor distraction to his domestic policies, and even as he begins authorizing tens of thousands of new troops, he’s blindly convinced a victory is impending. But though he blusters, manipulates, and strong-arms in his efforts to govern, there are more intimate moments, particularly with his wife and daughter, where the real man emerges and it’s clear how agonizing it is for him to wear this crown.

The play is a meditation on one of the oldest themes in the book: absolute power and how it can destroy those who wield it as completely as those upon whom it is inflicted. But there are disturbing contemporary allusions. J. Edgar Hoover’s (Richard Elmore) insistence on using the power of the Executive Branch to eavesdrop electronically on civilians may not have been widely known during Johnson’s presidency, but after Edward Snowden it almost feels quaint. Race riots in Ferguson, MO are not merely echoes of Watts, 1965 or Detroit, 1967, but glaring reminders of the causes behind the violence exposed on TV then. And there’s even a kind of nod to the stalemate in contemporary politics, as some of the biggest cheers erupt when LBJ basically tells a stonewalling congressman to shut up and do things his way. We may bristle at the notion of executive action, but you can almost feel a sense of relief and admiration among the audience for a politician actually using his office to get someone to fall in line or else.

The play is a meditation on one of the oldest themes in the book: absolute power and how it can destroy those who wield it as completely as those upon whom it is inflicted. But there are disturbing contemporary allusions. J. Edgar Hoover’s (Richard Elmore) insistence on using the power of the Executive Branch to eavesdrop electronically on civilians may not have been widely known during Johnson’s presidency, but after Edward Snowden it almost feels quaint. Race riots in Ferguson, MO are not merely echoes of Watts, 1965 or Detroit, 1967, but glaring reminders of the causes behind the violence exposed on TV then. And there’s even a kind of nod to the stalemate in contemporary politics, as some of the biggest cheers erupt when LBJ basically tells a stonewalling congressman to shut up and do things his way. We may bristle at the notion of executive action, but you can almost feel a sense of relief and admiration among the audience for a politician actually using his office to get someone to fall in line or else.

These suggestions of modern life mean that while The Great Society isn’t as taut as All The Way’”nor as intimate or as detailed a character study into LBJ’s brilliance and masterful manipulation’”it absolutely feels timelier. As costume designer Deborah M. Dryden writes in the program, the first play dealt primarily with politicians in suits, but the second is enmeshed in turmoil outside of Washington D.C., with protesters, peace marchers, rioters, troopers in gas masks, and the military on stage.

It’s an uncanny experience wondering at times if you’re watching a play set 50 years ago or today’s nightly news.

photos by Jenny Graham

The Great Society

Angus Bowmer Theatre

Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, OR

scheduled to end on November 1, 2014

for tickets, call 800.219.8161 or visit www.osfashland.org