UP THE RABBIT HOLE

There’s been a good deal of speculation over the last hundred-and-something years regarding the sexuality of Charles Dodgson, an Oxford professor of mathematics more famous for his writings under the pen name Lewis Carroll. Severally, storytellers Dennis Potter and Robert Wilson have investigated the subject; so have many market-minded biographers. That Dodgson never married is a fact; that he liked little girls more than he liked other kinds of people seems well-established; and that he took many photographs of nude little girls is a matter of extensive record.

That the little girls’ parents were usually in attendance is also inarguable; as well, the fact that postcard-style photographs of nude children were so ubiquitous in strait-laced Victorian England as to boggle the mind of those living today, in what is characterized by the politically correct as a less repressive era. Whether a society rife with images of nude children is a worse place than a society in which any public discussion of children comes loaded with legal and psychological hysteria is not for me to say.

Lily Blau too avoids saying anything about that in her very promising new play about Dodgson’s relationship with the eleven-year-old Alice Liddell; in fact she entirely omits mention of his nude photography, the presence of which would reduce any modern play to a sad and narrow little presumption. If it resists going all the way to psychopathology case study, The Missing Pages of Lewis Carroll (which Blau developed in collaboration with Sydney Gallas through years of workshop productions) does veer at times under apparent obligation to a reductionist agenda, suggesting that an adult male who wants to spend time with children not his own must have a sinister, if unconscious, motive. The play has other problems too, but few, and under the direction of Abigail Deser at Boston Court, the world premiere production is as exciting a showcase of new writing as I’ve seen in some time.

Pleasantly short on narrative and long on language, especially imagery, this story concerns what might have happened during certain days, entries for which are, in fact, missing from Dodgson’s diary. This sort of thing is always risky. The potential for irresponsible gossip is rife; Gregory Moss’s House of Gold deconstructs the JonBenet Ramsey case with the restraint and finesse of a famished carnival rat. But what Blau instead provides, and Deser expands, is a delicate, constant interflow of fact and fancy, scene after literate scene quietly propelling story and character.

What is most edifying in the play, and, happily, what we see most frequently, is the sight of a middle-aged man interacting as tutor and playmate with his boss’s kids, his falling in love with the most lovable of them, and she with him. We get just enough of Christ Church College politics, and of domestic wrangling in the Liddell household, to root the circumstances and to support the themes of liberalism warring with suppression, and of vice lurking inside of virtue. Largely, this is a wonderful world in which to spend a couple of hours.

What Blau has trouble supporting are the play’s gimmicky tendencies toward Lewis Carrollism: the idyll-threatening Mrs. Liddell makes an appearance or three as the Red Queen; Dodgson’s conscience is represented by a chatty knowitall of a White Rabbit. Dodgson’s occasional drops down the rabbit hole of self-loathing are represented as a trip to a hellish geometrical Wonderland – the mathematician’s migraine-induced epilepsy is never mentioned, but seems to be represented anyway, in a disappointing extension of the text’s mostly outstanding subtlety of revelation. Too, the climactic break with the Liddell family is underwritten to the point of obscurity; thus, the question of the diary’s missing pages is never adequately addressed. While the playwright admirably avoids exploitation and sensationalism, she also strays from issues she might have done better not to bring up in the first place.

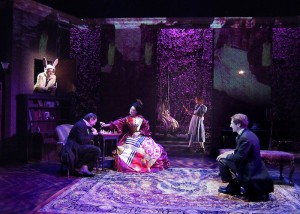

For the most part these problems are invisible in this typically gorgeous Boston Court production; as do most shows at this 99-seat house, this one looks like a million bucks. One wonders why other plays produced so close to Hollywood typically lack acting this good (casting by Raul Clayton Staggs). Stephen Gifford’s set, Jenny Smith’s props, and Garry Lennon’s costumes, as lighted by Jaymi Lee Smith, similarly raise the question of comparative adequacy: the theater professional I brought to the show was especially staggered by the revelation of space. Deser’s assemblage of elements, though it abets the unnecessary scenes inside Dodgson’s head with an overwrought abuse of Keith Skretch’s video and John Ballinger’s sound design, otherwise entirely elevates what is excellent in the writing.

The director’s work with actors is particularly tasteful. Together the two leads are Deser’s most handily-wielded tool. Leo Marks’s voice (the stutter when talking to grown-ups! the orotund vowels around children!) is even more impressive than his face and body; his Dodgson is a full, complicated, completely sympathetic human being. As Alice, Corryn Cummins is not merely convincing but equally fascinating as an innocent child, a mischievous object of desire, and a disappointed adult. As the other Misses Liddell, Erin Barnes and Ashley Ruth Jones delight and effectively project the trappings of childhood as well; Barnes impressed me especially given how much less mannered and more at ease with period she is here, under Deser, than she was in Theatre Banshee’s The Importance of Being Earnest under Sean Branney.

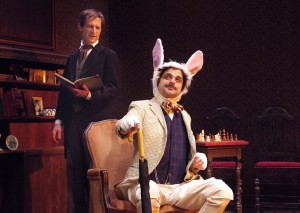

Time Winters and Erica Hanrahan-Ball, as Dean and Mrs. Liddell, are everything they ought to be and, gloriously understated, less than they might. Jeff Marlow’s White Rabbit, who also represents various ancillary characters but never removes those big white ears, is not at all bad. But in keeping with the weakness of the writing around this role, he is oddly modern and smug as the rabbit-conscience; predictably gross as the publisher MacMillan; et cetera. The script does this actor no favors, and the good performer’s inability to make this part work is another indication that the play has one more darling-killer of a draft between it and pure wonder.

photos by Ed Krieger

The Missing Pages of Lewis Carroll

The Theatre @ Boston Court

Boston Court Performing Arts Center

70 North Mentor Ave in Pasadena

Thurs-Sat at 8; Sun at 2

ends on March 1, 2015

for tickets, call (626) 683-6883 or visit www.BostonCourt.org

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

You nailed it!!

. . .also love the metaphor of the “famished carnival rat.”