INHOSPITALITY IN A HOSPITAL

A few weeks ago I spent a couple of nights at a hospital waiting for someone to be born. A couple of weeks later I spent a few more nights at the hospital, including time at the ICU, trying to keep the mother comfortable while she tried to stay alive. In all of this time at the hospital, my friend’s family was supportive, loving, and quiet. They were there to help, to make things better. They cooperated in making their loved one’s situation easier, and in assisting the work of the medical professionals.

This is not the family that comes to the ICU in ICU.

After their middle-aged son has an alcohol- and cocaine-related heart attack, dad (Joe Pacheco) and mom (Caroline Aaron) drag along their daughter (Dagney Kerr) to descend upon a nameless Manhattan hospital like a cacophonous triptych of furies, only all they really punish is each other. You know: a family. Over the course of a rather long couple of hours, we learn more about them than we’d like, including much that’s hilarious and a fair amount that’s very serious – their denial, their co-dependence, their inability to nurture despite their abiding love – but nothing that’s going to change our lives for worse or better.

When we meet them in the waiting room, the family has already been kicked out of their son’s room, and is repeatedly threatened with removal from even the common areas and eventually the hospital itself. That they aren’t ever removed, despite constant loud obnoxious interference with hospital routine, is indicative of the half-lengths to which the play and its production have gone, and why this show is so disappointing despite a fistful of outstanding elements.

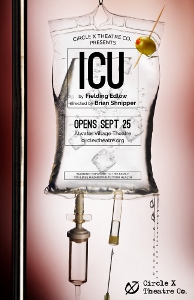

To a large extent, author Fielding Edlow and director Brian Shnipper collaborate happily to detail a very funny circumstance just this side of farce. Shnipper whips up a frenzy in which sitcom-ready jokes often seem more like inspired madness. The main characters are well-drawn in the script, and the actors are excellent, and many of the situations are well-defined and well-mapped. And for the first half of the first act, Shnipper has a strong handle on the loony, overlapped, crescendo-prone banter that defines this family and this world. But even early on, there are problems.

Like Aaron and Pacheco, Kerr brings a sharp, specific, credible character. But unlike them, she doesn’t fully embody the heightened reality of this universe. Aaron and Pacheco are ready when this script takes unwieldy turns from bathos to pathos to way-over-the-line farcicality. Kerr isn’t, quite; her timing, her quirks are too realistic to do the circumstances justice. As a result of the director’s inability to get her onto the same plane as the actors playing her parents, her character looks less grounded than buried up to its ankles.

The problem is by no means Kerr’s and Shnipper’s fault alone. Edlow has written an impossible job for a director, a tonally mercurial play that at the end of the first act starts to make gestures toward a gravity that, as often as it fails to integrate with the overall emotional world, is summarily abandoned. And in the second act, when circumstances devolve all the way to slapstick buffoonery, nobody knows what to do. They all try their best.

The supporting characters too, and their attendant actors (Shaun Anthony as a doctor, Ericka Kreutz as a nurse, and the outrageously immediate Doug Sutherland as a mysterious gentleman caller), are enlisted in an unwinnable war on the side of a script that makes more gestures than sense. Everybody has to veer from reality to reality as the play crashes against order, logic and proportion. Everybody except Tony DeCarlo as the patient: he spends much of his time in a coma, and when he wakes he has but one reality to play, which he plays faultlessly.

The script refers repeatedly to the paint-peeling, generally rundown condition of the hospital, but Amanda Knehans’ set is a beautiful, clean and orderly environment in which to spend an immersive couple of hours. Even this you-are-there element, in which the audience is placed around the walls in chairs exactly as unpleasant as those in a real hospital, falls apart once the scenes aren’t set in the waiting room anymore.

photos by Jeff Galfer

ICU

Circle X Theatre Company

Atwater Village Theatre, 3269 Casitas Ave.

ends on October 31, 2015

for tickets, visit Circle X

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

We saw the same play and also the same problems. I came away appreciating the cast but not the play. You put my disappointment into words.

Thanks.