SOMETHING UNSATISFYINGLY APOCRYPHAL

There are a few things that might not be entirely true about the Blank’s “World Premiere” of Jeff Tabnick’s Something Truly Monstrous, which opened last night in Hollywood. To begin with a quibble, a two-hour show by Tabnick called Barrymore’s Body, with what sound like most of the same elements, went up for five performances during the New York International Fringe Festival in 2004. But in this age of rolling world premieres, what’s eleven years, give or take.

The main thing that’s fiction here is probably the premise, but that’s the wonderful part. One of the best-ever pieces of Hollywood legend (likely spawned by Earl Conrad, the ghostwriter who made up Errol Flynn’s automythology My Wicked, Wicked Ways) is that in 1942, director Raoul Walsh stole the bloated, alcoholic corpse of actor John Barrymore from the mortuary and propped it up in Flynn’s house. Flynn was so shaken to see his dead friend sitting in the living room with a cigarette and a drink that he was almost unable to continue having sex with an underage prostitute.

The problem with the story is that:

- most of the tales in the delicious Wicked, Wicked are discredited fabrications, just like much in David Niven’s two delightful volumes of memoir, The Moon’s a Balloon and Bring on the Empty Horses, the latter of which contains choice yarns about pranks Niven and Flynn played on each other. But in Horses, Niven actually claims not to believe the Barrymore story (partly because he seems not to understand how rigor mortis works). This seems ungracious in one who asked so much credulity of others.

- the writer Gene Fowler, a drinking buddy of Barrymore’s who was if not the most reliable witness at least probably more so than Earl Conrad, is said by his son to have sat up all night with Barrymore’s body until it was interred – a remarkable claim in itself – without anybody stopping by except a prostitute.

In the story’s favor:

- From his Simi Valley retirement, Raoul Walsh told the Copley News Service in 1975 that Flynn was badly frightened when Walsh did in fact spirit Barrymore’s body up to Flynn’s Mulholland Drive estate.

And one more oddity:

- among various versions of the story floating around, including one involving W.C. Fields, Paul Henreid told one in his own autobiography in which it was Humphrey Bogart and Peter Lorre who stole the corpse.

Essentially every heavy drinker in or around Hollywood in May of 1942 has been linked to the theft of the dead thespian. But it was Henreid’s Bogart and Lorre tale that interested Tabnick, not least because at that time and place, a movie called Casablanca was being shot at Warner Brothers, featuring Bogart, Lorre and Henreid.

Tabnick’s play, now on display at the Blank under the direction of Daniel Henning, has many funny moments and some good dialogue, and contains one long sequence worthy of sustained interest. For this sequence, Henning makes much of rear-projection car-driving scenes (video by Rick Baumgartner & Eric Carabasi; lighting by Jeremy Pivnick). For the first half, about 50% of the dramatic action logically exploits established character traits and circumstances. What good writing there is, comes early. Later on, things become less active and more tedious.

Bogart (Jason Paul Field) and Lorre (Amir Levi), kvetching on the Casablanca set, take twenty minutes to establish that a) Barrymore is dead, b) Bogart is an insecure actor who thinks Casablanca is “pig shit” that won’t help his career, and c) Lorre is a morphine addict who’s about to sign a seven-year contract with Jack Warner. Feeling guilty about leaving a life of artistic poverty with Bertolt Brecht in order to play goons in American B pictures, Lorre decides to steal Barrymore’s body and dump it at Warner’s house: an act so monstrous that Warner will blacklist him from every studio in town, thereby ensuring that Lorre does something useful with his life.

It’s a ludicrous idea that makes no sense whatsoever given that Warner has already threatened to blacklist Lorre for cursing and insulting him. And the fact that Bogart doesn’t say so – only that stealing the body is a bad move politically – is probably the second-biggest hole in the fabric of the script, after the requirement that two actors play two other, iconic, very imitable actors. The temptation to do caricatures is just too much, and really the script plays on tropes specific to these stars; so what ends up happening is that one must cast spot-on impressionists who are also actors, or else one loses the script’s novelty value. The show has other imperfections.

Throughout, characters spout travelogue dialogue that clunks with exposition instead of saying things people would actually say in any reality. Exacerbating this situation is the fact that Tabnick shoves into the characters’ mouths what seems like every bit of research he ever did about these historical figures. The script also has a dearth of actual drama, given that the stakes for these characters are pretty low overall. An offstage deus ex machina takes care of all the worries in about 2 minutes flat near the end, which shows how much the writer thought of the dilemmas he wrote. Unfortunately this easy fix comes after a long stretch in which nobody does anything but sit around and wait for someone who never comes – at the wrong house, to boot.

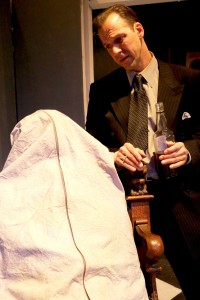

The production’s greatest strength is Amir Levi, whose Lorre impression is decent but whose broad mugging is perfectly matched to Henning’s mock-the-Golden Age tone. It’s a very persuasive, one might say bullying performance in that nothing else onstage is nearly as right, so by contrast everybody else looks not-so-good. Field is obviously a good actor and he’s very game as Bogart, and he looks the part, but his mannerisms are in and out. Though they get more consistent as the play goes on, still he exemplifies the script’s trap, and ends up less acting than impressing his way through. And when Henreid shows up to very mildly complicate things, actor Jilon Van Over does a mid-Atlantic accent half the time, a vague Teutonic the other half – besides which, he has none of the poker-up-the-ass stiffness that characterized Henreid onscreen. So while his characterization may be the most thorough overall, and the least guilty of chasing a parody, it’s also the odd man out.

I was so unmoved by this particular version of a Hollywood mythology that I’ll indulge myself by relating an Errol Flynn story from John Huston.

Once at a party when they both were young, Huston announced that he had a trial of honor to pick with Flynn over a woman. Flynn obliged immediately by knocking Huston down. Having heard that Flynn was an unscrupulous fellow, Huston scrambled to get up very quickly. Flynn knocked him down again, and again Huston scuttled to his feet as fast as he could. Flynn said something like, “Look here, John. I’m not going to kick you, you know.” And the director said that he was glad to hear it, and the next time he got knocked down he lay there long enough to decide that the woman in question may have had the right to make up her own mind in the choice between himself and the biggest movie star in the world. And then Flynn helped him up and they had a drink together and agreed that if Huston would stop calling him a son of a bitch, Flynn would stop knocking him down.

Huston was not himself the most reliable anecdotalist, and it’s not a great story. But it’s short. And you should hear my John Huston impression.

Something Truly Monstrous

The Blank Theatre

2nd Stage Theatre

6500 Santa Monica Blvd. in Hollywood

ends on November 8, 2015

Fri and Sat at 8; Sun at 2

for tickets, call 323.661.9827 or TheBlank.com