SUICIDE ISN’T PAINLESS

My dad had a great record collection. At 16, I would drive over after school to smoke cigarettes and listen to Stan Getz. One afternoon I found Pop putting his affairs in order. The divorce had broken him. Whiskey had taken its own toll, and an ill-advised romance had sucked up his severance from the only good job he’d ever had. He told me he was going to kill himself and that I should take the things I wanted from his house. The air hung over the bonsai in shafts of sun, dead still, as if the room were being preserved for what I had to imagine as an indifferent posterity.

I said okay and went over to the stereo. I put on an item he kept for a joke, a saccharine barbershop quartet called the Hi-Lo’s doing “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries,” and said “I want this.” Pop laughed hard enough not to kill himself that day. I felt the sense of total accomplishment you can only feel at sixteen, before you understand consequence. I was sure I’d done right. I was maybe even a little bit of a hero and apparently I still think so; I’ve certainly told this story before.

By 58 my dad had devolved past humor, more or less homeless, more or less a drug addict. I was no longer at all certain I had done a good job in keeping him alive. I had recused myself from his querulous middle age and I dreaded responsibility for his dotage. When he hanged himself, politely and with some dignity, in a practical sense he did me a favor. A son’s father is his god, so when mine killed himself the sky opened up and handed me a go card.

His mother didn’t see it that way. She shared some of his emotional problems, and bereavement seemed to precipitate her rapid descent into dementia. My mother didn’t like it either; she had divorced him twenty years before but over a decade later she still suffers, knowing that the man she loved as a girl died alone and without hope. We found notes he’d scribbled over the course of years, in his acrimony and petulance, in his anguish. They are not edifying. He is better dead.

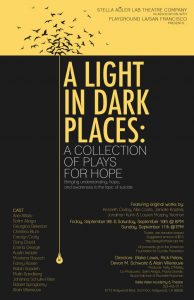

Many people don’t view suicide as I do, as a wholly autonomous right, either because their experience differs or because they haven’t any. This past weekend Kelly O’Malley produced three performances of five one-acts about suicide. In the program notes O’Malley included a message to her father, whom she will carry in her heart always. I don’t know how she feels about suicide, but I presume that a daughter’s love was a causal instrument for this show. An outward gesture of grief is often a good, when it doesn’t involve stealing airplanes and flying them into buildings, and this one doesn’t, and I thank O’Malley for the gesture I saw on 9/11/16. I’m sure Light helped someone. It might have helped more if it had more focus and less uneven writing and presentation. Three-fifths of the evening were memory plays, and it’s a tough act to achieve drama from past event in ten minutes.

Light opened with a triptych of soliloquies by Kenneth Cosby entitled “Hello?” in which Emma George played the schoolgirl victim of sexual bullying, Ariel Alflalo played a soldier haunted by friendly-fire guilt, and Allain Villenueve played an emotionally disturbed employee. Villenueve’s by-default direction consisted of having the characters walk in a circle, taking turns delivering front-and-center  litanies. The staging served neither piece nor performer; pacing lagged, tension dissolved. The actors clearly were left to make their own choices. Like the material, most were appropriate if unsurprising. The women were fine. Villenueve is a good actor hampered by half-intelligible English.

litanies. The staging served neither piece nor performer; pacing lagged, tension dissolved. The actors clearly were left to make their own choices. Like the material, most were appropriate if unsurprising. The women were fine. Villenueve is a good actor hampered by half-intelligible English.

Janielle Kastner’s “Feed Me” concerns a cat (an excellent Fanny Rosen) left behind by a suicide whose family (Montana Roesch, Robert Sprayberry) is too bereft to care for her. Kastner is a little on-the-nose but very engaging in her layout of the cat’s confusion, less successful in the humans’ totally extraneous dialogue. Devon M. Schwartz directed with purpose but did not take into account the limitations of the space: You can’t lay people on the floor when shallow audience risers enforce a waist-up sightline back of the second row. And you don’t need two beds or a cat tower or interstitial pauses you could drive a hearse through to present a lights-up/lights-down mood piece.

Lauren Murphy Yeoman’s “Phaethon” has poetry in its monologues from a dead junkie (Dany David) and his blue-collar mother (Johanna Schulte-Hillen), punctuated by outstanding music (guitarist Rabih Saadeh, soprano Christina Blum). As directed by Villenueve, the piece achieved a mysterious histrionic grace; it was the only play of the evening in which I didn’t know what was going to happen next. It was also the only one that featured moments of direction so silly and overwrought that I had to stifle giggles.

Allie Costa’s “A Moment of Silence” is a trite soliloquy about gender choice, in which a girl born as a boy (Malin Sandberg) explains from the afterlife that her politician mother (Carolyn Crotty, appropriately appearing as if in search of egress from a thankless part) forced her to suicide by putting her through conversion therapy. The writing has more agenda than art and under the purported direction of Rick Peters the play was almost unbearably stagnant. But even mouthing maudlin propaganda, Sandberg is a performer of native charm. And she knows how to find her light.

The last play was Jonathan Kuhn’s “Looking Forward,” a decently-written manic-pixie dreamgirl comedy set at an airport restaurant. Blake Lewis directed briskly; Georgina Bekerian was fittingly adorable, and Austin Iredale displayed good comic timing as the lonely neurotic she befriends. Salim Aliaga made the most of his bits as a dramatically unnecessary waiter. Closing with this feel-good piece was as smart a gesture toward structure as the evening received.

Treating various themes (reach out for help; think of those left behind; be nicer to each other) in disparate modes (mostly didactic) and styles (realism, magical realism, grand guignol) is no way to illustrate a thesis, especially when there is no thesis, no investigation, only bare gesture flailing at the face of implacable destiny. Is something – anything – better than nothing, in such a case? If art is therapy for the artist, it is labor for the audience. My catharsis will only ever come from revelation communicated to me, not hoarded by the production.

I didn’t stay for the talkback immediately following the performances, as the perfunctory show had not suggested I would find anything else of value on the premises. It is entirely possible that the talkback would have made me think differently about the choice of ending a temporal existence. I’ll never know, as I’ll never know what horrors my father saw coming and was unwilling to endure. And neither will shows like this, well-intentioned as they may be, know or explicate anything about the loneliest hearts. When they’re thrown together too sloppily for artistic value, theme evenings can feel morbid and opportunistic, gouging the audience for goodwill it would be callous to withhold. Their real service is to the writers, who can only weigh their work via production, and to the desperate performers, who get the opportunity to act in something – anything. In sweaty little Studio C at the Stella Adler Lab, theirs is the hope I was able to find.

A Light in Dark Places: A Collection of Plays for Hope

Stella Adler Lab Theatre Company

in association with Playground LA/San Francisco

Stella Adler Lab Studio C

6773 Hollywood Blvd. in Hollywood

closed on September 11, 2016

for more info, visit Stella Adler Lab Theatre Company