PRESENT THREAT

While Do Not Resist only partly takes place in Ferguson, Missouri, several minutes of immersive, haunting footage place the film in the rare company of The Battle of Algiers and Bloody Sunday. But the civil unrest Pontecorvo and Greengrass filmed was staged. Accompanied by producer Laura Hartwick, Craig Atkinson filmed the Ferguson protests as they happened in 2014. Atkinson and Hartwick stay invisible; they let the police and citizens speak for themselves. The heroic camerawork and editing make you wonder why all of St Louis didn’t burn; the film makes the overturning of police cars seem a duty.

But the movie isn’t about Ferguson. It’s about a mindset peculiar to the American law-and-order crowd. In this new documentary, police in riot gear prep for a protest march by watching a TV bodybuilder do arm curls. We each choose our own agitprop, Atkinson seems to say; his own quietly-delivered bombshell is that American policing has run rampant in the last thirty years, and that it’s harming us as a society, and that it’s only getting worse. If it’s not news, that in itself is good reason for the movie to exist.

It’s a stomach-churning vision of small-mindedness and big government. With no narration, Atkinson allows police to reveal themselves as astonishingly simplistic and callous. He insists that he didn’t plan it this way, but he seems to have cast very well: Every single person Atkinson shows supporting the ramp-up of military-style policing, such as the routine urban deployment of SWAT teams in 20-ton war-surplus vehicles, comes across as at best a dim bulb, at worst a venal bully.

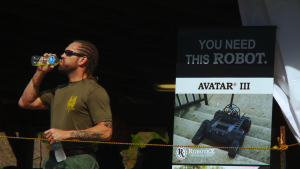

A few seem frankly psychotic, like “#1 police instructor in America” Dave Grossman, a former West Point psychology professor who writes violent science fiction novels (The Guns of Two-Space) and academic books (Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill). Grossman also operates a traveling Christian-oriented military school called Killology Research Group, named after a discipline he has invented. Grossman’s close-set eyes and wagging brows create an unphotogenic effect of derangement; when he preaches of an end times-level crime wave about to sweep America, and a roomful of cops nods in unison, it’s easy to feel uneasy.

Grossman has taught thousands of police that they embody, for moral and practical purposes, three mythological icons of American aggression: cowboys, front-line troops and superheroes. He’s on the road 300 days a year, at academies and conventions in all 50 states, lecturing that violence is central to effective policing. But, he says, it comes with the perq of having the best sex of your life after you beat someone or kill them.

The officer who shot Philando Castile in Minnesota had, incidentally, recently completed Grossman’s Bulletproof Warrior seminar. The Grossman mentality has become the standard in American policing: It is better to kill a citizen than risk injury to an officer. This principle, coupled with the certainty that a uniform embodies justice, is echoed in the words and actions of police on ride-alongs throughout the movie. The SWAT raids depicted are grim to watch, embittering to the legally victimized, thrilling to the enforcers. They are also entirely unproductive.

Young white officers describing the giddiness of carrying assault rifles on no-knock warrant raids, are juxtaposed with a black student who sees three generations of his family handcuffed and their windows broken in, guns pointed in their faces, for a pipeload of marijuana and the cash in the kid’s pocket. The SWAT supervisor is sorry the raid was such a failure. But that’s his job. He is reconciled to a 50% failure rate for raids involving ten riot cops in an armored personnel carrier against a gross haul of $800 and a gram and a lot of hard feelings.

The application of combat equipment and psychology to civil police work is a growing phenomenon thanks to trainers like Grossman and to a $40 billion glut of military hardware dumped onto the police-welfare market with no accompanying training and no oversight or tracking of usage. A third of the equipment seems to be new or unused, a fact which raises questions about the military-industrial complex that orders, manufactures and parcels out these devices. FBI director James Comey and military disbursement officials are quick to defend the taxpayer-funded distribution of war machinery on American soil, but at one hearing, an unusually subdued Rand Paul demands an explanation for a Pentagon delivery of 12,000 bayonets to rural police departments. There is no answer.

As Do Not Resist winds down, its menace broadens. Aerial surveillance techniques developed in Afghanistan are now used to track American citizens so that in case they commit crimes, they can later be traced back to the scene. Algorithms are in place that scientists believe can accurately predict the criminality of unborn children based on a few factors, including income and race. And an array of police brass talk about the prediction and prevention of crime by targeting potential suspects with an array of questionable techniques, including facial recognition software and social media keyword sweeps. Arrest someone before they commit a crime? “Why not,” asks an LAPD sergeant, “when you’ve got all the information you need?”

The senators, veterans and harassed citizens Atkinson employs to speak against this dystopian reality are uniformly eloquent in rejecting the occupation of American towns by autonomous militias. The case of this movie, that our police are out of control, is very effectively made. But watching it, I felt that it was to the detriment of the argument, and unnecessary, that the case was made with bias against opposing viewpoints.

When I asked him about this, Atkinson didn’t entirely disagree with the criticism. He admits that his film fails to showcase a reasonable counter-argument, but not for lack of trying. He says that, a year into making the film, his access to police dried up as Ferguson flared. He has spent the last two years making a different film than he intended, and he has tried to find cops who made good points in their own favor. “I had to go with the people who showed up,” he says, and those people said what they said.

I believe him, though Atkinson pointedly opens Do Not Resist with the tenth night of Mike Brown demonstrations in August 2014. He chooses not to show the much-reported violence on both sides during those weeks, because that’s not the story he’s telling, but rather a day when police brutally enforced a curfew against no resistance. Later, in context of an understandable reaction to justice denied, he does show the burning of a police car and assorted hooliganism after the officer’s grand jury refuses to indict. This is certainly the filmmaker’s prerogative, and the film does not claim impartiality.

What I found more suspect was Atkinson’s contextualization of data. The film suggests that it is entirely to our detriment that American SWAT deployments have risen tenfold. The film omits the fact that violent crime has declined in the period by 50%, partly thanks to a 600% increase in incarceration. There is, therefore, a possible argument in favor of inflated, aggressive policing; I would not make it, but it exists. Dave Grossman (pictured below) has been making that argument for 20 years, but he does not make it in this movie.

Atkinson answers that while crime is mostly down, there have been recent spikes, and that he shot footage not included in the film showing data cruncher Richard Berk telling police that he takes as a given circumstance that every chief fudges when reporting crime. Atkinson further argues that CompStat, the broadly accepted police data-management tool that is the origin of most American crime statistics, is a flawed device. Atkinson is not the first to point out that CompStat allows for creative input (aggravated assault can be entered as simple assault, etc) and therefore abets underreporting, since it’s used not only to measure crime but also to measure a department’s effectiveness and to justify requests for operating funds. University of Chicago scholars and others have questioned CompStat’s impact and its ethics, arising as it does from the controversial “broken-window” movement that transformed New York City under police chief William Bratton.

It also bothered me that the most alarming technology bandied in the film, predictive behavior data, is left open as to its applications in law enforcement, if any. Is this empty showmanship on Atkinson’s part, or a thread for the audience to ravel on its own? Atkinson says that his stylistic decision to avoid talking heads, coupled with repeated denials of permission to film the applicable police procedures, made it impossible to show the impact, real or potential, of some of the technologies and policies discussed. I have to categorize this answer as not quite meeting the criteria for due diligence.

Regardless, if this extraordinarily skilled and talented filmmaker is fueled by paranoia, it seems justifiable. The son of a SWAT captain, Atkinson appears to have no inherent bent against police per se. But he has been scared by a hell of a team, including the FBI director. In a year when American crime rates were by every reported measure the lowest since 1966, Atkinson filmed Comey baldly informing a roomful of police chiefs that they were in fact threatened by a dramatic rise in crime that could only be suppressed with military weapons and military protocols. Later in the film, a South Carolina sheriff says that fear of ISIS made him order an MRAP assault vehicle to conduct search warrants – fear of ISIS, and of missing out: The million-dollar truck, designed specifically to withstand land mines in a desert environment, came to the green hills of Carolina free of charge.

Do Not Resist closes with a warning that self-activated technology will soon determine practice in police protocols, but by then the film has shown that the human factor is already far down the list.

Filmmaker Craig Atkinson

Filmmaker Craig Atkinsonphotos courtesy Vanish Films

Do Not Resist

Vanish Films

72 minutes | USA | 2016

in limited release

opens Friday, October 14, 2016

in Pasadena at the Laemmle Playhouse 7

in Santa Monica at Laemmle’s Monica Film Center

for more film festivals and other screenings, visit Do Not Resist