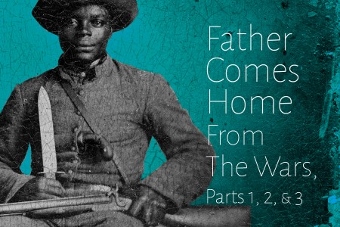

A HERO’S JOURNEY FROM 1862

SPEAKS VOLUMES FOR OUR TIMES

Father Comes Home from the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 first played in 2014 at NYC’s Public Theater, yet Suzan-Lori Parks’ play presciently anticipated the media focus that racism would receive throughout 2017. With the conversation on race being a headline story this year, her play is even more timely now than it was three years ago.

Father Comes Home from the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 first played in 2014 at NYC’s Public Theater, yet Suzan-Lori Parks’ play presciently anticipated the media focus that racism would receive throughout 2017. With the conversation on race being a headline story this year, her play is even more timely now than it was three years ago.

Parks, the first African-American woman to get the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, in 2002, draws from aspects of the Greek classic The Odyssey as she creates the tale of her hero, literally named Hero (Wrekless Watson), who begins his odyssey as a slave on a plantation in West Texas in 1862. Hero is faced with a lose-lose conundrum: His master will be heading off to defend the confederacy and needs a valet. He has offered Hero this role with the promise that, at the end of the war, he will be granted his freedom—if the man can be trusted. On the other hand, as a horseless footman, it is not unlikely that he will be killed or seriously injured before the war is over. If the North wins, it will have been for nothing. If the South wins, he will have to live with the guilt that he did his part to support the system that keeps him enslaved.

The tension builds as the conflicting opinions are expressed by his peers: His love interest Penny (Tamara McMillian) fears for his life and dreads his absence; and his father-figure “Old Man” (a delightful Antonio TJ Johnson) wants to be proud of his “son” doing more with his life than being a slave, with the potential for freedom. Other slaves are torn between wishing that, perhaps, just one of them could have a better life and their certainty of retaliation by slavemaster “The Colonel” (Tom Stephenson) if Hero says no. Homer (Cortez L. Johnson)—named after the author of The Odyssey—has a dark history with Hero and the motives behind his orations are, initially, harder to ascertain. With such varied input and information unfolding, our Hero is pulled in multiple directions before he makes his choice at the end of Part 1.

The sophisticated phrasing of the slaves surprises; we don’t expect to hear these characters speaking with such eloquence. In stark contrast to period stereotype, the languaging of these plantation workers is frequently poetic—almost like a modernized Shakespeare at times. It serves as a tribute to the intelligence behind these individuals who were not permitted to be conventionally educated.

The show is presented with Parts 1 and 2 in a long first act and Part 3 for a short second act—all told 2.5 hours. Transitioning to Parts 2 and 3, time has passed and new characters are introduced, but the plot progresses such that it simply feels like one play with three acts.

Describing the plot of parts 2 and 3 would undermine the delicacy that Parks puts into letting Part 1 unfold. Suffice it to say that the latter parts deal with the ramifications of Hero’s choices and the impact is riveting. One feels the whole audience holding their breath awaiting another key decision by Hero at the end of Part 2.

Father Comes Home is not a musical, but Parks does employ singing by the ensemble of slaves at times to convey emotion and plot, most notably by Leonard Patton whose strong voice gives pathos to his words.

Parks brings unique insight into the mindset of the time. Hero cannot fathom what freedom would be like or if he sees all of the benefits for a black man. Hero explains in Part 2 that if he were ever stopped by officers and said that he was owned by the Colonel, he’d be safe, but if he were a free man, likely they’d kill him. He posits, “’¦then the worth of a colored man when he’s free is less than the worth of a colored man when he’s owned!”

Parks brings unique insight into the mindset of the time. Hero cannot fathom what freedom would be like or if he sees all of the benefits for a black man. Hero explains in Part 2 that if he were ever stopped by officers and said that he was owned by the Colonel, he’d be safe, but if he were a free man, likely they’d kill him. He posits, “’¦then the worth of a colored man when he’s free is less than the worth of a colored man when he’s owned!”

Providing a fascinating look into the mind of the other side, the most memorable monologue belongs to the Colonel. The agile Stephenson takes us on a delicious journey through compassion and disgust for the slave owner. He is simultaneously sympathetic, vile, and merely a product of his times. But therein lies the question: Is he so different than the people on T.V. this summer? Or simply living in a society when acting upon his racism was, horrifyingly, normal? Even the Colonel himself says, “History would find it barbaric,” yet, even knowing this, he clearly does not himself. As interesting as many of the characters are, it is the Colonel that lingers in the mind because we live with him today.

Part 3 veers towards the surreal in the final section, with Durwood Murray playing a talking dog; it’s extremely entertaining and artistically troubling at the same time. Parts 1 and 2 work so hard to successfully create the bitter realism of the time that adding this absolutely out-of-place character is jarring.

Eventually, we have no choice but to try to suspend our disbelief to accept the character, but it never quite fits with the first two parts. On the positive side, Murray’s portrayal is so loveably delivered that he becomes one of the fondest memories of the play—even yielding the evening’s only show-stopping applause; the dog also ends up delivering one of the most poignant lines of the script.

Costuming by Jeanne Reith is befuddling. Modern clothing choices are anachronistic, such as a runaway wearing a hoodie and the Old Man wearing Crocs. This reminds us that the issues live on today, but distracts from the period feeling and seem out of place in a somber contemplation on the struggle for freedom. What’s more, because the slaves’ clothing is quite ordinary, Part 3 starts out confusing us when three actors are re-cast to portray three new people. Re-using actors happens in many plays, but costuming is normally how we know it is someone different; we lose that tip-off here.

With a strong cast and excellent dialogue, the show feels complete by the end, yet learning that Parks is finishing parts 4 through 9 left this reviewer eager to see what comes next on our Hero’s journey.

photos by Daren Scott

Father Comes Home from the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3

Intrepid Theatre Company

Horton Grand Theatre, 444 Fourth Ave

Thurs at 7:30; Fri at 8; Sat at 3 & 8; Sun at 2

ends on October 22, 2017

for tickets, visit Intrepid