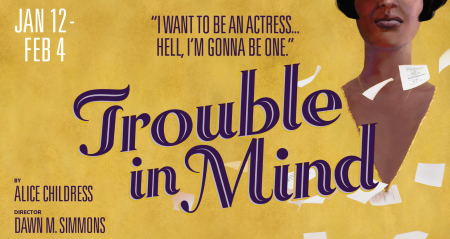

GOOD TROUBLE

The Lyric Stage production of Trouble in Mind, directed by Dawn M. Simmons (co-producing artistic director, The Front Porch Arts Collective), is well worth seeing, if only for the wonderful Patrice Jean-Baptiste (recently memorable as Petruchio in Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s Taming of the Shrew). Jean-Baptiste’s dry wit and emotional insight, as well as her humor, cynicism, and passion make the leading role of Wiletta the moral and dramatic focus it should be.

Playwright Alice Childress directed the opening run of her first full-length play when it premiered off-Broadway in 1955. Despite the possibility of a Broadway opening in 1957, Childress refused to rewrite the script to soothe white sensibilities. Even so, it seems she must have tweaked the script a bit between 1955 and 1957, because as produced today, it includes references to the Little Rock school integration struggles of 1957. Whatever the events of the 1950s, nearly everyone who encounters this play about backstage tensions among a mixed-race cast and crew of that era, is astonished by its timeliness.

Nonetheless, Trouble is not without its troubles. In a time when so many productions are staged in a fast-and-furious 90 minutes with no intermission, the 140 minutes (including intermission) required for this one seems long. I suspect that were Childress alive today, the pressures to rewrite would have to do with pacing as much as with politics. Despite these shortcomings, the Lyric’s production offers an opportunity to appreciate this examination of the intersection of compromise and courage, racism and privilege, and commerce and honesty.

Childress’s refusal to pull her punches meant the 1957 Broadway opening never happened. The play languished for decades after its off-Broadway run, an ironic mirroring of the situation in this play about a Black actress who reaches her limit with stereotypes and dishonest portrayals of African-Americans in white-dominated theater.

A handful of regional productions in the late 20th century were followed by increased interest in the early 2000s. The play finally reached Broadway, where it received four Tony nominations in 2021. A month after the Broadway opening, it was staged by London’s National Theater, and now, Boston audiences have an opportunity to enjoy the many gifts of this work, including MaConnia Chesser as the sassy and practical Millie Davis, Wiletta’s rival and sometimes ally; Kadahj Bennett as the earnestly ambitious and clueless John Nevins; and Davron S. Monroe as the elderly Sheldon, whose vivid recounting of a lynching he witnessed as a child pushes Wiletta into taking on the moral obligation that may bring an end to her acting career.

Throughout the course of the play, Black cast members form backstage alliances and rivalries; the arrival of white cast and crew—most significantly Barlow Adamson as the intransigent director Al Manners and Allison Beauregard as what might be called “the foolish (white) virgin” Judy Sears—further complicates these relationships.

One strength of Childress’s writing is the way each character advances the story while maintaining a distinctly individual identity. Robert Walsh (Henry) is on stage for a relatively short time, yet his role is crucial to Wiletta’s transformation. At seventy-eight (though he imagines he looks much younger), the otherwise forgetful former stage electrician-now-doorman still recalls Wiletta’s performance of twenty years ago, when she “looked so pretty and sounded so fine.” Henry’s recollection of Wiletta in better days at the beginning of the play seems to give Wiletta the strength to push back against the lies that the script of the never-performed play-within-a-play calls for.

Henry and Wiletta are alone together again at the end of the play, and Henry urges Wiletta to do the thing she always longed to do, “something grand.” With only Henry as her audience, she recites a Psalm: Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity. Back in the 1950s, Trouble in Mind was widely praised, but a number of critics felt the final moments of the play were overly didactic. If Wiletta recitation from the Bible was indeed the final word of this play, that criticism would be justified.

But the last thing the audience hears isn’t Wiletta’s voice. It is the “canned applause” that has mocked an earlier speech filled with meaningless platitudes. It’s this final touch that adds a tragic element to Wiletta’s courageous effort, an element that transforms her from merely admirable to truly heroic.

photos by Nile Hawver

Trouble in Mind

Lyric Stage Company

140 Clarendon Street in Boston

ends on February 4, 2024

for tickets, call 617.585.5678 or visit Lyric