THE STORY’S THE THING IN UPDATED VERSION

OF THE OPERA AN AMERICAN SOLDIER

This is a heartbreaking story impossible to forget. Although suicide is the second leading cause of death in the U.S. military (unintentional injuries being the first) some people still consider bullying completely normal, a rite of passage that will make the victims tougher no matter how much grief it causes. An American Soldier is an opera that recounts the true story of 19-year old Danny Chen, the Manhattan-born young soldier who was racially harassed, bullied and mercilessly beaten on an almost daily basis by his superiors and fellow soldiers before he died of suicide on October 3, 2011, in Afghanistan.

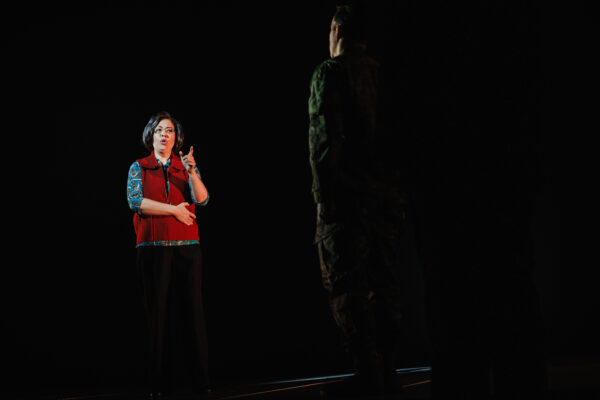

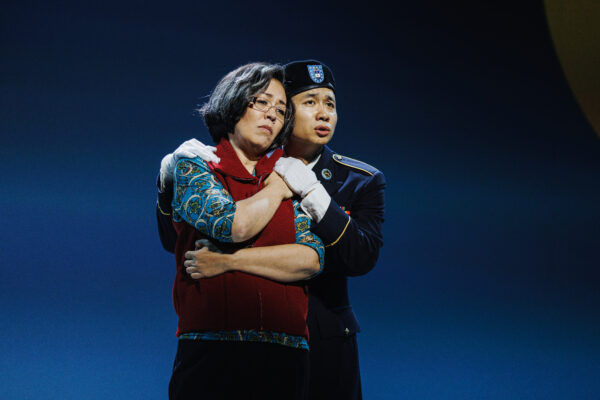

Commissioned by Boston Lyric Opera and Perelman Arts Center NYC, very close to Danny’s home, told through the music of virtuoso composer Huang Ruo, with libretto by David Henry Hwang, and directed by Chay Yew, the opera — which opened May 14 for one week only — documents the year and a half between Danny’s high school graduation and his death, using his tormentors’ trial as the main thread. The names of the eight officers indicted were changed but the story is recounted almost as a documentary. It opens with the trial where the earthy, powerful bass-baritone Christian Simmons plays the Military Judge (and, like most other actors in this opera, also plays other soldiers,) Ben Brady is the Trial Counsel, and tenor Joshua Sanders the Defense Lawyer. James C. Harris, Bolivian soprano Shelén Hughes, and mezzo-soprano Cierra Byrd are other soldiers giving testimony; all of them make a well-cast, talented ensemble. We hear bits and pieces of what had happened to Danny while we see him moving around as a frustrated ghost who cannot get anybody’s attention. Played by dynamic tenor Brian Vu, we find out that Danny was born and lived in Chinatown with his two hard-working, loving parents: his father Yan Tao Chen toiled ten hours a day in a restaurant; his mother Su Zhen, played by the remarkable Nina Yoshida Nelsen, worked as a seamstress and adored her son. She is also called to give testimony at the trial.

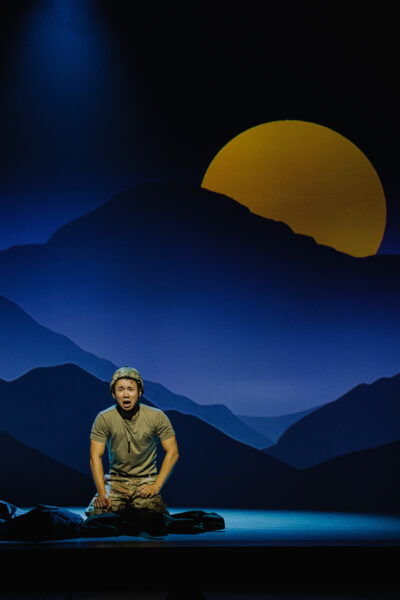

We then go back to the beginning of the story, in Chinatown, where Danny and Josephine, played by lively soprano Hannah Cho, who gave an exquisite performance, are two teenagers who just graduated high school and are dreaming about their future while hanging out downtown. A bright, good-natured kid, Danny wants to serve his country instead of accepting a full college scholarship for many reasons, mainly because there were no Asian-American heroes in American movies, comics or videogames in 2010, even though the first Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States in the 1840s. The stage setting by Daniel Ostling is bare and at the same time romantic, using compelling backdrop projections by Nicholas Hussong (the moon in Chinatown with New York fire escapes and roofs; the hot sandy moon in the Afghanistan camp), and clear-cut lighting design by Jeanette Yew to establish location and time for each scene. Two side monitors outside the stage frame,had subtitles written in English and Chinese.

Like Josephine, Danny’s mother is against his choice; he is her only child, a devoted son who did well in school and could have a safe future but Danny doesn’t budge. He is sent to Fort Benning in Georgia, and writes to his family in January 2011: “I’m suffering here but it’s not too bad so far.” His letters tell us a sweetened version of what is truly happening, “Everyone likes country music ’¦ weird as hell to me” or “the Drill Sergeants say fuck like every sentence.” He knows his parents can’t read English text but he is sure Josephine will translate it and his curses would be edited out; the girl and his mother sit around the table downstage left while we see his life in the camp. “They ask if I’m from China like a few times a day.” His fellow soldiers call him “Chen” in a goat-like voice, “Jackie Chan”, “egg-roll”, and many other derogatory terms. But, he writes, “Don’t worry ’¦ people respect me for not quitting.” Most people drop from basic training; in March he writes “People here are leaving left and right… all of the weaker people have either left or gone home… now I’m the weakest one left.”

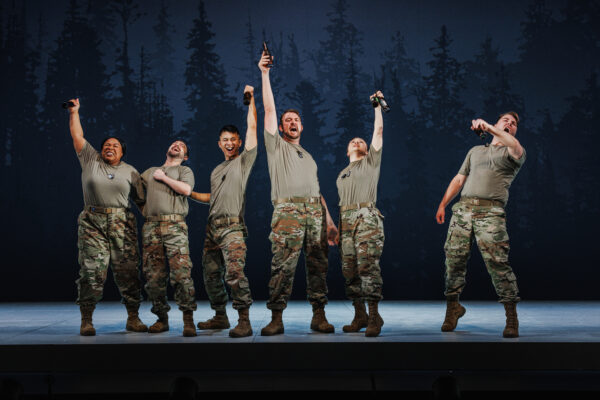

In mid-May, Danny is sent to Fort Wainwright in Alaska, a new member of the 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, known as the “Arctic Wolves.” Other soldiers from his platoon are deployed to Afghanistan and he is left behind. Danny is resilient and makes new friends although the racial abuse doesn’t stop, they even have “Racial Thursday”, a day where soldiers are supposed to insult each other, some medieval BS that is supposed to alleviate tension and boost morale. He arrives in Afghanistan in August and he is sent to a combat outpost in the Kandahar Province. Instead of being hurt by the enemy’s booby traps and ambushes, Danny is tortured by his superior, 26 year-old Sgt. Marcum (Alex DeSocio) who put him immediately at the bottom of the social hierarchy, making him the perfect target: a skinny smart teenager from the big city who never saw a combat zone, beside being the only Chinese-American in his unit. DeSocio gives us the perfect creep with his enraged, nervous acting and deep singing.

We hear his superiors’ excuses to cover for his brutality whenever we go back to the trial: “not fit enough,” the Sergeant wanted “to correct mistakes,” so we see him order Danny excessive physical exercise to do every day including sit-ups, sprints, long runs while carrying a heavy sandbag, push-ups with a mouthful of water he was not allowed to swallow or spit out, all while being harassed and humiliated, but Danny doesn’t give up. For six long weeks he endures the abuse on a daily basis, even the “excessive guard duty” to the point of exhaustion only to be punished when he accidentally falls asleep, dehumanized in front of his peers by people who were only a bit older than he was, cowards who never had much power in their own lives but ended up on a massive power trip. In a moving duet, Josephine and Danny look at the moon from opposite sides of the globe, and Ruo’s music is sweet but eerie.

On September 27, Sgt. Marcum yanks him out of bed and drags him across sharp rocks as punishment for supposedly breaking the hot-water pump, causing bruises and cuts on his back. One week later, a distraught Danny is late to report for guard duty and when he arrives at the tower, he realizes he’d forgotten his helmet and water. Sgt. Marcum forces him to go pick them up and then to crawl, with all his equipment, across a long field of sharp gravel in order to return to the tower. While he is on the ground, he encourages other superiors to pelt him with rocks to “simulate artillery,” and humiliate him: “gook”, “dragon lady”, “chink.” We see him go up the ladder to enter the tower and we hear the sound of a gunshot.

production photos by Jeremy Daniel

poster photo by Jai Lennard

An American Soldier

Perelman Performing Arts Center’s John E. Zuccotti Theater

World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan, 251 Fulton Street

two hours with intermission

ends on May 19, 2024

for tickets (starting at $29), call 212.266.3000 or visit PACNYC