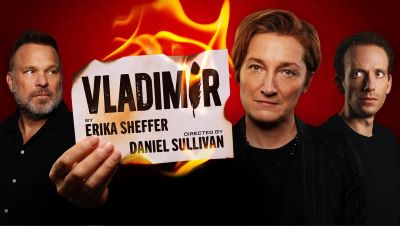

PUTIN ON THE FRITZ

The most entertaining part of Manhattan Theater Club‘s Vladimir, which opened tonight at NY City Center, was the tirade the woman sitting behind me went into during intermission, pointing out to her companions the play’s numerous historical inaccuracies, double standards, instances of naiveté, ignorance and anti-Putin propaganda, as well as its general worthlessness, both as a dramatic work and as a pseudo-historical document presented as a piece of political criticism.

Listening to this woman, an American who demonstrated a broad and nuanced understanding of Russian history, culture and politics, as well as a decent taste in theater, I was at a loss to find anything I disagreed with. Just as I am at a loss to find any legitimate artistic reason for why playwright Erika Sheffer — who shows no meaningful grasp of her work’s setting or characters, and offers only trite, generic insights into its themes — decided to write the thing in the first place.

Francesca Faridany and Norbert Leo Butz

Under Daniel Sullivan’s unhelpful direction, Vladimir begins on Mark Wedland’s busy, disjointed TV-studio set with a prologue: It’s New Year’s Eve, 1999, and a drunk Boris Yeltsin (Jonathan Walker), after relieving himself into a vase, delivers a televised national address naming Vladimir Putin as his successor. It’s funny — an inebriated president urinating into a flower pot. And if at that moment the theater had caught fire and the audience was evacuated, everyone could have gone home imagining the hilarity that might have ensued were it not for an act of god. Instead what follows is 2004. There is a war in Chechnya, and Raya (Francesca Faridany), a journalist covering the conflict for an independent publication, who is critical of the Russian government and sympathetic to the Chechen rebels, is becoming a thorn in Putin’s side. Her editor Kostya (Norbert Leo Butz), who finds himself in a precarious position with the Kremlin over Raya’s articles, urges restraint. And Raya’s soon-to-be-married daughter Galina (Olivia Deren Nikkanen) doesn’t want her mother returning to the war zone. Their fears are substantiated when Raya finds herself poisoned.

Francesca Faridany and Norbert Leo Butz

Raya’s storyline competes, then intertwines, with that of Yevgeny (David Rosenberg, who creates the only sympathetic, grounded and believable character in the entire show). A downtrodden Jewish accountant in a land of institutional antisemitism, Yevgeny overcomes his timidity and cowardice when he embarks on a quest to find the identities of the entities behind the high level corruption and graft undermining the legitimate business of his American expatriate boss Jim (also Mr. Walker).

So why does Ms. Sheffer choose to set her story in 2004 Russia, despite having no understanding of the place? The answer is Vladimir Putin. He is the villain of the moment, a monster, war criminal, and megalomaniacal dictator who wants to destroy Ukraine, then take over Europe. Everyone agrees and so no investigation, or even context, is necessary. He’s an easy target. But are clumsy attacks on easy targets really the stuff of good theater? And is there not enough corruption in U.S. government and business for Ms. Sheffer to explore her themes in a milieu she is presumably more connected to and whose nuances she can grasp more easily? Are voices here not censored, and careers, livelihoods and reputations not ruined, for expressing unpopular opinions? Are scientists not blacklisted when the results of their legitimate peer-reviewed studies are found to not correspond with current notions of political correctness? Are medical procedures not performed or denied based on the latest political trends? Did we not, just two years before the main events in Vladimir take place, invade a sovereign country for no legitimate reason, and cause immeasurable destruction and suffering, completely destabilizing an entire geopolitical region, and causing havoc that is still reigning and will continue to reign for decades to come? And was this travesty not supported by much of the American media? Did Lincoln, arguably the greatest American president, not start a war with the South when it tried to secede — or, to put it another way, gain independence — from the Union (like the Chechen rebels who in Vladimir are trying to gain independence from Russia)? Was a whistleblower who exposed the extent to which the U.S. government secretly violated the privacy of its citizens not forced to flee the U.S. to Russia because it was the only place on the planet where he could escape certain incarceration for what likely would have been a very long time?

Francesca Faridany and David Rosenberg

If a writer is talented, and passionate about their subject, they need not know the objective reality (imagining for a moment that something like that exists) of the world they are writing about. They can invent it according to their own vision. And if what they have to say is personal and necessary, and if they say it in an elegant and truthful way, then the result will be authentic and meaningful, even if some details aren’t how they are in real life. Such is not the case with Vladimir. Ms. Sheffer’s hollow characters, empty conversations, unnecessary storylines, and banal observations all create the impression that her ultimate reasons for telling this story were born of vanity rather than of any kind of artistic or moral necessity.

If readers are interested in learning about some of the real people the characters in this play are based on, they should look up the Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, an American-British businessman Bill Browder, and Sergei Magnitsky.

Additional cast: Erin Darke, Erik Jensen.

photos by Jeremy Daniel

Vladimir

Manhattan Theatre Club

New York City Center, Stage 1, 131 West 55 St.

2 hours and 15 minutes including one intermission

ends on November 10, 2024

for tickets, call 212-581-1212 or visit NY City Center