I was a teen in the ’70s and I can assure you that everybody in Europe over 13 who wasn’t living under a rock knew something about the Butter Scene in Last Tango in Paris, the 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci and starring Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider. You could not escape the despicable comments, the bar jokes, the comedians’ satires following the media’s chauvinistic portrayal of the main actress. Being Maria (2024), a biographical drama directed by Jessica Palud presented at the 77th Cannes Film Festival, is here to remind us not to repeat the same mistakes. It delves into Maria Schneider’s experience during and after the making of Tango, a very thorny subject. Palud’s direction is empathetic but unflinching; she navigates the complexities of Schneider’s experiences with sensitivity but she is brutal in depicting the painful aspects of the film’s production and its aftermath. The screenplay by Palud and Laurette Polmanss is based on the book by Vanessa Schneider, cousin of the actress who died in 2011.

The film starts with a short, intimate glimpse into Schneider’s life before the making of the film: Maria, played by a very gifted Annamaria Vartolomei, is a hopeful young actress burdened by a hard and resentful mother (Marie Gillain) who throws her out of the house at 15, and an absent, superficial father (Yvan Attal) who is a known television and film actor. Unfortunately, important parts of Maria’s early career are absent, like her relationship with Brigitte Bardot who saved her from homelessness and introduced her to important people in the business. The film goes almost immediately to the meeting with Bernardo Bertolucci (Giuseppe Maggio) when Maria is 19, a minor in the early ’70s.

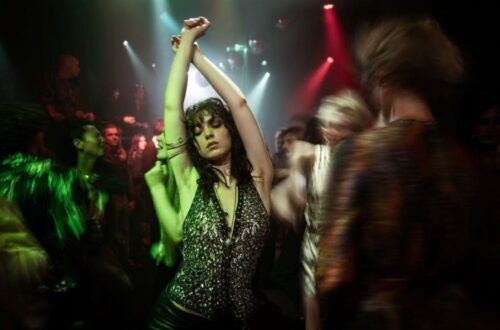

Bertolucci’s documentary approach to movie making and his identification with Marlon Brando (a very believable Matt Dillon), his obsession in revealing what he thought was Brando’s true nature, is an appealing part of the character until it goes too far. Dillon admired the actor his all life and it is obvious that he studied the uncomfortable part meticulously to get as close as possible to the complex thespian and succeeding. When Brando’s character rapes Schneider’s character, the disturbing scene is filmed without the knowledge or consent of the actress and in front of a shocked, silent crew.

Palud, while using an intimacy coach, reproduces it as viciously as it was in the original version. Schneider was not fully aware of the specifics of the scene when it was filmed because Bertolucci and Brando had intentionally kept the details from her. Bertolucci publicly acknowledged that ”At that moment, I wanted her to really experience that situation,” all to get “her reaction as a girl, not as an actress. I wanted her to feel truly humiliated.” Somehow justifying his unethical, chauvinistic behavior in the name of artistic vision, making us question the limits of art. Was the scene essential to the story, was it an example of exploitation, or was it simply meant to provoke a scandal? Five years earlier, Andy Warhol had presented Blue Movie, an adult erotic film showing explicit sex and, after an initial outrage, it received a wide theatrical release with many praises from the art world.

Tango is banned as expected but it is Maria who has to deal with the ugly consequences, mocked by most, feeling violated, humiliated, and deeply traumatized. With only her uncle Michel (Jonathan Couzinié) on her side, she falls into drugs; even her new love affair with lovable, dedicated Noor (Céleste Brunnquell) can’t save her from the predictable downfall. Cinematographer Sébastien Buchmann uses an observational, stationary camera approach and many close-ups, forcing the audience to confront the ethical ambiguities and the emotional gravity of the narrative. Every time Buchmann uses tight shots to capture Vartolomei’s expressions, the actress impeccably conveys the emotional weight of Schneider’s struggles.

The film unfolds at an uneven pace: Thomas Marchand’s editing alternates a classic narrative flow with hard cuts that I think intend to mirror the tumultuous nature of Schneider’s life, evoking a sense of disorientation often stopped by moments of languorous silence and stillness. The sound design by Benjamin Biolay is subtle and minimal, underscoring key emotional moments without overwhelming the dialogue or the stillness in the scenes.

Schneider’s story is told with the respect and complexity it warrants and it challenges viewers to reflect on the intersections of art and ethics, on identity, objectification, and the psychological scars left by trauma. Schneider once said: “It was a cinema of men, for men,” even though it was cloaked in colorful ’60s trends like sexual and artistic freedom, equality, and disdain for the bourgeoisie.

Being Maria

France | 2024 | 100m | biopic

opens today, March 21, in NYC at the Quad

opens March 28 in LA at the Nuart

with a national expansion on April 4, 2025