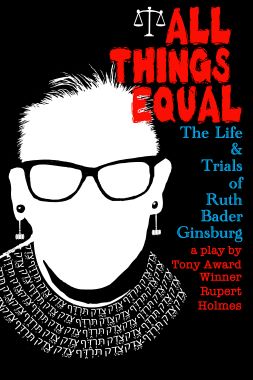

FROM NOTORIOUS TO VICTORIOUS

Michelle Azar vividly invokes the spirit of famed jurist Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Rupert Holmes’s one-woman show All Things Equal. As implied in the play’s subtitle The Life and Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Ginsburg faced many trials in and out of the courtroom. Set in Ginsburg’s chambers at the United States Supreme Court, Azar begins by reading from an essay: “We are part of a world whose unity has been completely shattered,” she begins, and ends by calling for a renewal of the “brotherhood of man.” Ginsburg looks up at her imagined audience of two high school students, friends of her granddaughter’s, who are writing a paper about her, and comments dryly that she was in eighth grade when she wrote those words. She adds that she would revise the wording today to eliminate terms like “brotherhood of man.”

Ginsburg goes on to review her life, starting with the death of her older sister of meningitis when Ginsburg was a baby. We learn that while Ginsburg was valedictorian of her Brooklyn high school, she never delivered her valedictory speech because her mother died of cancer the day before her high school graduation. Yet her mother, who went straight from graduating from high school at the age of 15 to working in New York’s garment district, had managed to save $8000 (the equivalent of $100,000.00 in 2024) for Ruth’s continued education.

Ruth was on her way, but her way was not an easy one. Despite being the first woman to make Law Review at Harvard Law and graduating first in her class at Columbia Law (she transferred after her husband was offered a job in New York) while mothering a toddler and attending classes on behalf of her husband while he underwent cancer treatments, she could not get a job. Law firms rejected her because of her sex and because she was Jewish. She eventually became the first tenured female faculty member in the history of Columbia Law, but more important, she co-founded the Women’s Rights Project, mapping out strategy and acting as counsel for the ACLU. In a twist of one of the ACLU courtroom trials, she found cases in which men faced discrimination due to gender, e.g., a man denied a caregiver tax deduction available to women at the time and another man denied survivor’s benefits available to widows but not widowers and used these decisions to overturn laws that discriminated against women.

This has the potential to be dry or come across as whiny, but Azar captures Ginsburg’s excitement, philosophical grace, and good humor in her tackling of these cases. We see as well Ginsburg’s devotion to husband Marty who survived his cancer and became a trophy husband, if we can define that as one who does all the cooking and is unstinting in his support of his spouse, campaigning behind the scenes to win her an appointment to the Supreme Court.

Ginsburg, as portrayed by Azar, is most passionate when discussing two things: the first was the strategy she used in breaking down legal barriers to equal rights, and the second was opera. In one terrific scene, Azar portrays Ginsburg lip-synching to an aria from Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

We enjoy insights to Ginsburg’s friendship with and affection for Antonin Scalia, one of the most conservative members of the Court; her amused reactions to her elevation in her old age to the Notorious RBG meme and cult figure; her devotion to her daily exercise routine (we witness her performing a series of moves to her “disco classical” playlist). Azar pulls off all of this as though she is indeed in her mid-eighties, moving slowly and stiffly but with the determination that seems very true to the woman we know Ginsburg to have been. It was a surprise to see Azar in the lobby following the show and see that she is nowhere near her eighties.

Toward the end of the show, Ginsburg addresses the elephant in the room. Why didn’t she step down while Obama was in office instead of giving Trump yet another Court nominee? The answer is simple and obvious — she thought (as did so many) that Clinton would win. Ginsburg, who was initially nominated by Bill Clinton, would likely have derived tremendous satisfaction in giving the nation’s first female president, who happened to the be wife of the president who appointed her to the Court, the opportunity to make her own judicial appointment to replace her.

Alas, that did not take place. Toward the end of her life, as the court grew more and more conservative, Ginsburg’s role was increasingly that of writing dissents. Her dissents, she says, are “blueprints for the future,” a future that she hopes will transform her from “notorious” to “victorious” in her fight for equality. She closes her performance with the following challenge to her listeners — and all of us: “Whenever you see something unfair, unjust, or unequal,” she urges, “you have to say two words: I dissent.”

photos by Thee Photo Ninja and Bing Liem

All Things Equal – The Life and Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

2024 pre-Broadway national tour

reviewed at Emerson Colonial Theatre in Boston on Feb 3, 2024

for tour dates and cities, visit Ginsburg