BILLIE’S LIFE WASN’T NO HOLIDAY

The title actually says a lot. When a star as bright as Billie Holiday, the sultry jazz singer whose career lasted from 1929 to 1958, is performing at a bar and grill in her hometown of Philadelphia, late in her career, something is clearly amiss. Billie explains that she loves playing small, intimate clubs like Emerson’s more than she does venues like her handful of big nights at Carnegie Hall. As the show goes on, though, we come to see that her life story and her personal decline is more of the reason behind her no longer getting bigger gigs.

For those unfamiliar with the unforgettable Billie, her unique, sultry whine can be heard at here to have a sense of why she was captivating. As interesting as her unique voice is, her story is equally fascinating. Following an adolescence filled with trauma, she turned a horrible dance audition into a singing opportunity and began a series of performances in Harlem nightclubs in 1929, leading to her discovery by music producer John Hammond in 1935. What should have been the start of a hit career was beset by overt racism, poor choices in male companionship, alcoholism, a prison term for a crime that was committed by her man, and eventually heroin abuse. Yet right to the end, Billie knew in her heart that singing was where she was at her best, no matter what her condition.

Lanie Robertson’s script gives Karole Foreman the chance to do a cabaret-like tribute to about a dozen of Holiday’s songs. As well as Foreman sings, the power of the show is far more in what she says between the songs. Holiday pulls no punches with her audience from the start, sharing with her Philly followers stories from her rocky road tour, being treated horribly in town after town solely for being black. Bandleader Artie Shaw, she tells us, tried to shield her from some of the pain by having the all-white, all-male band join her for meals in the kitchens, since she was forbidden in the dining rooms, but she felt the sting nevertheless, especially in one club that she details with all the spite as if it had happened the day before.

As the show progresses, though, Holiday drinks heavily between songs and starts losing her focus and composure, gradually becoming a mess who isn’t just blunt, but is saying too much. Her anchor, gifted pianist Jimmy (Damon Carter), is clearly as much babysitter to her as accompanist, suddenly breaking into the introduction of the next song when she goes onto tangents that he knows should be stopped. It is painful to watch this legend falling apart as the show goes on, yet always coming through specifically when singing. Well, almost always –which adds to the drama.

Foreman very much carries the show, as Carter (the only other person in the production) only has a handful of lines in the 90-minute one-act. Still, Carter speaks volumes with his looks at both her and us, making the most of Jimmy’s difficult situation with the few utterances he gets.

Rather than making a strong attempt to impersonate Billie’s inimitable crying tone, Foreman keeps it simpler by using her own strong vocal ability to bring out the poignancy in the songs, especially one of Holiday’s most remarked-upon ballads, “Strange Fruit,” which is about lynched black men hanging from a poplar tree (here is a powerful video of Billie singing it shortly before she died). Though she frequently performed this song, Billie found it hard to do so, because it reminded her of her father’s unnecessary demise because they couldn’t find a hospital that would help a black man in time.

Director Wren T. Brown doesn’t rush Foreman, giving Billie room to flounder, pause, get confused, and ramble, adding to the tenderness. We’re rooting for Holiday, but we also feel the futility in her actions, as does Jimmy and, clearly, other venues she has played at.

Admittedly, in the first fifteen minutes or so, one could think the show was just going to be a case of sing-reminisce-repeat for the whole ninety minutes, but once the liquor starts to flow, the pain in her monologues (accompanied by Foreman’s adept pacing of Holiday’s gradual decline through the night) tugs at the heartstrings. giving Cygnet attendees a powerful production.

photos by Craig Schwartz Photography

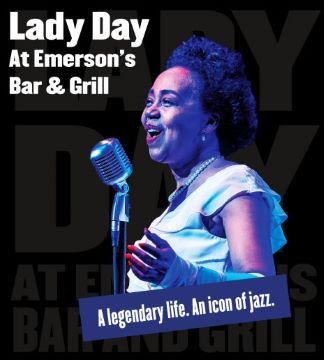

Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill

Cygnet Theatre Company

in association with Ebony Rep

Old Town Theater, 4040 Twiggs St.

Wed – Fri at 7; Sat at 2 & 7; Sun at 2

ends on Feb 18, 2024

for tickets, call 619-337-1525 or visit Cygnet