MAKING FACES

You’ve heard of a play-within-a-play? Award-winning playwright David Henry Hwang offers us a play-within-a-play-within-a-play in the semi-autobiographical Yellow Face. Lyric Stage’s production of the Obie-winning play, directed by Ted Hewlett, has much to recommend it — and a few problems.

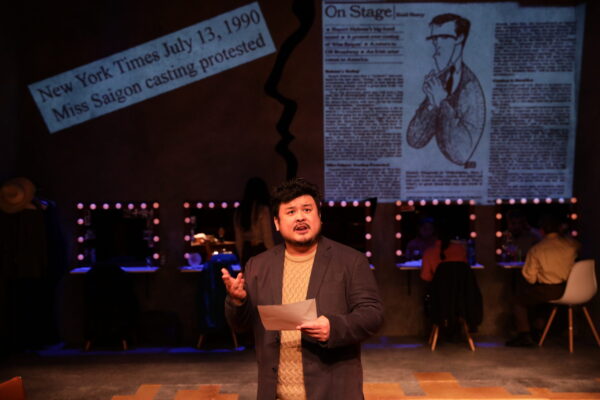

Let’s start by focusing on the play itself. It begins with the outrage on the part of the Asian-American community over the casting of a white Welshman, Jonathan Pryce, in a lead role in the extremely successful Miss Saigon musical in 1990. Miss Saigon, like David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, is a retelling of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, and Hwang (Michael Hisamoto), as a prominent Asian-American playwright, publicly protests the casting and then goes on to write his own play, Face Value, as a further denunciation of the practice of casting white actors as Asians.

In casting Face Value, however, Hwang chooses Marcus G. Dahlman (Alexander Holden) to play his lead. Dahlman appeared in a community theater production along with some Asian-American actors and Hwang likes him in the role he is filling in Face Value — even though his casting director (Jenny S. Lee) isn’t sure that Dahlman has any Asian heritage. There’s a funny bit in which she tries to determine Dahlman’s background without actually asking him about it (because legally she cannot ask him about his race). Eventually, Hwang realizes that he has cast a white man in an Asian role — exactly the thing he was outraged about in the casting of Miss Saigon. To cover up his mistake, Hwang refers to Marcus as Marcus Gee when they are addressing an Asian-American students’ group, and Marcus Gee becomes Marcus’s stage name — a name that will earn him further roles as an Asian-American man after Hwang has him fired.

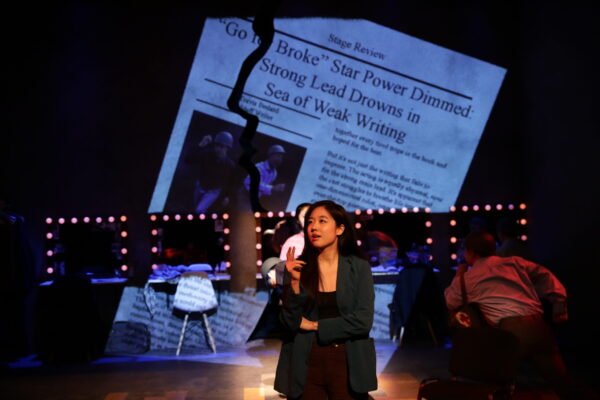

Marcus Gee goes on to win praise for playing the King in The King and I. In contrast, Face Value is a miserable failure, earning terrible reviews in Boston (for long-time Bostonians, it was fun to see Kevin Kelly’s panning of Face Value projected onto the large screen at the back of the set) and closing after 8 preview performances on Broadway. All this increases Hwang’s rage toward Gee for his own error. Gee, on the other hand, begins to identify more and more as Asian, becoming an activist and supporter of Asian-American causes and concerns. He even has a romantic relationship with Leah Anne Cho (Mei MacQuarrie), Hwang’s ex, which further infuriates Hwang.

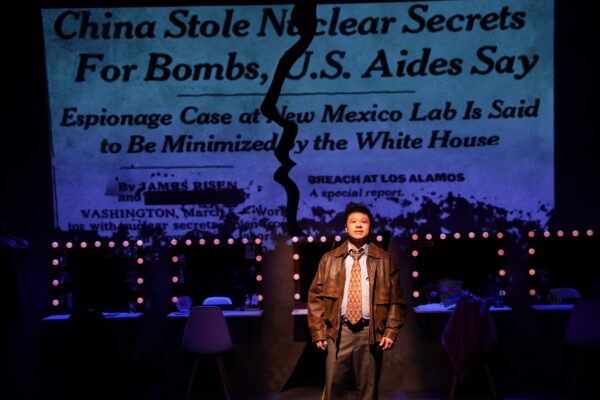

While all this is going on, Asian Americans, including fake-Asian Marcus, are being charged by Republicans in Congress with aiding the Chinese government in election interference in the 1996 election. (Yes, that really happened.) Hwang’s father (J.B. Barricklo), a banker, is under federal investigation, suspected of funneling money from China. And Wen Ho Lee, a Taiwanese-American nuclear scientist has been charged with conveying nuclear secrets to China.

The script is conceptually brilliant. It examines the challenge of considering race and of not considering race. It questions the meaning of race and the challenge of forming a community around race. Much of the play is not only auto-biographical, but even a documentary — projections of news articles support the script throughout. The factual and fictional elements of the story are folded in upon themselves in ways that kept me and my companion talking about it into the night.

Playwright Hwang does nothing to portray character Hwang in a positive light. When he’s not making a stupid casting errors and treating Marcus Gee unfairly for his own mistake, he’s wasting his time flirting in chat rooms and looking at porn. He even accepts a position on the board of his father’s bank, even though he admits he knows nothing about banking and is clearly only doing it for the money. Hwang’s willingness to portray himself as deeply flawed actually allows us to appreciate more fully the complexity of the questions raised by this script.

Hisamoto is excellent as Hwang, even bearing some physical resemblance to the photos I’ve seen of Hwang. Hisamoto’s portrayal seems so natural and authentic that I had to keep reminding myself that it was not actually Hwang on the stage.

Holden was equally intriguing and convincing as a liminal character who moves between racial identities. Born in Japan, Holden identifies as half-Asian and half-white, and he plays a white man who portrays himself as Asian — in other words, who takes on a “yellow face.” All the characters in the play, including many who are white, are performed by Asian actors, but Holden, as Marcus Dahlman/Gee, is the only one whose identity as Asian is questioned or defended by the other characters. I believe this is intentionally confusing, as both director Hewlett and playwright Hwang wanted their audience to challenge themselves regarding racial identities — and judgements.

All of these factors kept me engaged and glad to have seen this play, but having said that, there are many confusing moments in this production. I think it’s always a challenge when the same actors play multiple roles without significant changes in costuming (here by Mikayla Reid). In particular, Gee/Dahlman appears in multiple timelines, and while the conclusion of the play solves the mystery in a satisfying manner, his first appearance is confusing because we haven’t yet been introduced to him through the main storyline. I appreciated Megan Reilly‘s projections of documentary accounts of the historical events discussed in the play, but I could also see that text was being projected onto the stage floor — text that was obscured by Hwang’s desk on Szu Feng-Chen‘s otherwise basically empty set from where I was sitting. I have no idea how those projections might have aided or deepened my understanding of the production, but even without them, I came away with a deeper understanding of some of the events that have brought challenges to Asian Americans within and beyond the U.S. entertainment industry — and a renewed appreciation for David Henry Hwang as a playwright.

photos by Mark S. Howard

Yellow Face

Lyric Stage

140 Clarendon Street in Boston

ends on June 23, 2024

for tickets, call 617.585.5678 or visit Lyric