THE IMPERFECT STORM

Over lunch today, I tried to tell someone about Michael Elyanow’s new take on the Medea myth and found myself crying into my tikka masala. The material is horrifying enough in the Euripides version: a witch, having lost the affections of the lover for whom she has sacrificed everything, kills his new bride and his (and her own) children. So I may be excused for losing my equanimity once. I blew my nose, got hold of myself, and began again, but as late as the rice pudding I still had to keep breaking off to hold the tremor from my voice. I will not repeat the exercise now; in fact I will say little about the new story, because the joys of The Children, especially as directed by Jessica Kubzansky, are mostly in terms of revelation: narrative, physical, and above all theatrical.

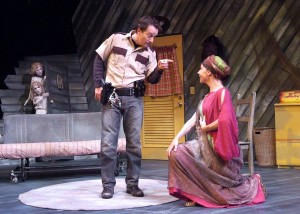

The odd thing is that I wasn’t emotionally moved in the theater, or on the long drive home; my initial appreciation was almost entirely intellectual. One would expect such a fragile conceit – to prevent their murder, the children (Sonny Valicenti, Paige Lindsey White, and a pair of masked puppets) are whisked away from ancient Corinth by a member of their own play’s Greek chorus (Adriana Sevahn Nichols) and their nurse (Jacqueline Wright) to the middle of a hurricane in modern-day Maine, only to confront a befuddled sheriff (Daniel Blinkoff) – to bring either immediate catharsis or derisive laughter. This one is at times funny, intentionally so, but I had to sleep on it and explain it to someone else for the visceral reaction to consume me. The reason is deceptively simple: in retelling the story at a table in a crowded restaurant I had the memory of Ms Kubzansky’s (and her designers’) wealth of stagecraft to assist me, without Mr Elyanow’s problematic pen to distract me. Ms Kubzansky has rendered a flawed play into a beautiful and lingering piece of theater. That it takes a while to sink in is a testament to the problems it has to overcome.

The odd thing is that I wasn’t emotionally moved in the theater, or on the long drive home; my initial appreciation was almost entirely intellectual. One would expect such a fragile conceit – to prevent their murder, the children (Sonny Valicenti, Paige Lindsey White, and a pair of masked puppets) are whisked away from ancient Corinth by a member of their own play’s Greek chorus (Adriana Sevahn Nichols) and their nurse (Jacqueline Wright) to the middle of a hurricane in modern-day Maine, only to confront a befuddled sheriff (Daniel Blinkoff) – to bring either immediate catharsis or derisive laughter. This one is at times funny, intentionally so, but I had to sleep on it and explain it to someone else for the visceral reaction to consume me. The reason is deceptively simple: in retelling the story at a table in a crowded restaurant I had the memory of Ms Kubzansky’s (and her designers’) wealth of stagecraft to assist me, without Mr Elyanow’s problematic pen to distract me. Ms Kubzansky has rendered a flawed play into a beautiful and lingering piece of theater. That it takes a while to sink in is a testament to the problems it has to overcome.

Mr Elyanow, having conceived of a fascinating if unwieldy narrative, has also written some scenes and dialogue of surpassing allure. His literary allusions welcome an experienced theatergoer but do not exclude the less educated; his rendering of heightened language mostly pleases, although as one character points out, this feature is more present than its merits warrant. But one wishes for more of it when confronted by its opposite number, Mr Elyanow’s use of modern language. In this regard his play frequently sounds as if it has been attacked by an avenging Fury, determined to make trite and ridiculous all his profound intentions. The predictable time-travelers’ anachronism jokes fall painfully onto ears prepared, by the brilliance and gravity of the production, to hear something less stupid. A plastic shopping bag gets a pointless and amusement-free analysis (“this pliable container branded with the markings of C, V, and S”), and an extended joke about what to call the children’s nurse devolves into “your sister, friend, whatever,” which I could swear is a line I’ve heard on a canceled mid-season replacement situation comedy. And when it reaches for pathos, the writing is more likely to hit its points on the nose than to back off to a more powerful refinement. At a play in which drowning is a present threat for several characters, I could have heard the admonition to “Breathe!” at least one time the fewer before the blackout.

This trend toward the unsubtle is nowhere less welcome than in the revelatory transition between the play’s precarious metaphor and its brutal melodramatic core. Just when it most needs finesse, the script is at its most obvious: the audible clunk about two-thirds of the way through, when these constituents separate into discrete halves, nearly knocked me out of the theater.

It didn’t, though, because this is among the best-directed shows you’ll ever see. Every actor on François-Pierre Couture’s breathtaking set (especially the absurdly talented Ms. Wright) knows exactly what to do and does it. The same can be said for lighting designer Jaymi Lee Smith, costumer Tina Haatainen-Jones, soundscapers Veronika Vorel and John Zalewski, and puppet maker Susan Gratch: there’s just nothing wrong there. Dramaturgically, Mr Elyanow’s story and plot points are sound, so Emilie Beck did her work, too; and I don’t want to minimize the value of what the playwright has done in wrangling this outrageous premise into a shaggy but recognizable beast. With a little work on certain very fixable elements, this writer can allow the other artists’ work to stop spending so much magic misdirecting audience attention from the play’s faults. Then the synthesis of everyone’s effort can lift this gift up to heaven, where it should please even the gods.

photos by Ed Krieger

The Children

Theatre @ Boston Court

70 N. Mentor Ave. in Pasadena

Thurs-Sat at 8; Sun at 2

ends on June 10, 2019 EXTENDED to June 17, 2012

for tickets, call 626.683.6801 or visit Boston Court