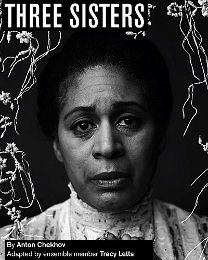

TRACY LETTS ADAPTS

THREE SISTERS FOR STEPPENWOLF

Tracy Letts calls his version of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters an adaptation, but other than some changes in language it’s still the great Russian dramatist’s play, a human and humane account of characters mired in boredom, disappointment, failure, loneliness, and frustration. The Steppenwolf is premiering Letts’ revision in a beautifully acted and staged revival that should make believers even out of those playgoers who avoid Chekhov as a tiresome purveyor of ineffectual people wallowing in ineffectual lives.

Tracy Letts calls his version of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters an adaptation, but other than some changes in language it’s still the great Russian dramatist’s play, a human and humane account of characters mired in boredom, disappointment, failure, loneliness, and frustration. The Steppenwolf is premiering Letts’ revision in a beautifully acted and staged revival that should make believers even out of those playgoers who avoid Chekhov as a tiresome purveyor of ineffectual people wallowing in ineffectual lives.

Letts retains the play’s setting, a provincial Russian town in the early 1900, where sisters Olga, Irina, and Masha Prozorov, the cultivated daughters of a deceased army general, live along with their brother Andrey. The sisters yearn to return to their Moscow home, where life is cultured and intelligent, but they remain with their hopes and dreams in the backwater town, one which is populated by mediocrities. The only civilized companionship comes from an army brigade stationed in the town.

The audience is tempted to grow impatient with Chekhov’s sensitive characters. They marry disastrously, allow their plans for a better life to peter out, and in general lack the will to take charge of their own lives. Andrey is an intellectual who hopes to become a university professor but he marries a coarse woman from the town who turns into a tyrannical bitch. Masha loves the married army officer Vershinin but tied herself to an ineffectual schoolmaster. Olga remains unmarried, bound instead to a local school as a teacher and eventually headmistress, a job she despises. Irina is the youngest and most optimistic of the sisters but eventually she, too, is ground down by the tedium of her provincial existence.

The audience is tempted to grow impatient with Chekhov’s sensitive characters. They marry disastrously, allow their plans for a better life to peter out, and in general lack the will to take charge of their own lives. Andrey is an intellectual who hopes to become a university professor but he marries a coarse woman from the town who turns into a tyrannical bitch. Masha loves the married army officer Vershinin but tied herself to an ineffectual schoolmaster. Olga remains unmarried, bound instead to a local school as a teacher and eventually headmistress, a job she despises. Irina is the youngest and most optimistic of the sisters but eventually she, too, is ground down by the tedium of her provincial existence.

The Letts adaptation follows the original narrative closely, the major departure being in the dialogue. Letts injects numerous modernisms in the language (“you guys”) and lots of profanity, especially from Masha. Letts is obviously looking for a more contemporary gloss to the dialogue, sometimes arbitrarily. In most translations, Masha’s schoolmaster husband in his pathetic optimism repeatedly proclaims “I’m content.” At the Steppenwolf, he repeats “I’m satisfied,” scarcely an improvement.

Possibly the most significant revision is in the title. Letts drops the customary “The,” possibly suggesting that Three Sisters gives the play a more universal inflection than the more specific The Three Sisters. If that’s his intent, it’s a subtle change that will be lost on many viewers.

Possibly the most significant revision is in the title. Letts drops the customary “The,” possibly suggesting that Three Sisters gives the play a more universal inflection than the more specific The Three Sisters. If that’s his intent, it’s a subtle change that will be lost on many viewers.

The chief achievement of the adaptation is not getting in the way of the original masterpiece. The main characters remain maddening in the way they allow vulgarity to triumph over their sensitivity. And they still drone on philosophically about the meaning of life and work while they allow life to pass them by. Instead of mooning about it for 11 years, why don’t the sisters just pack their bags and board the train for Moscow? But Chekov accepts his characters as they are, frail and flawed, and portrays them with compassion and sympathy. And he takes the audience with him, especially in the moving production at the Steppenwolf.

Director Anna D. Shapiro employs a passionate approach to the play. The anguish among the characters is outspoken, not muffled. The tears are torrential. There is no real physical action in the story and the only bit of violence takes place off stage at the end of the story. But the vividness of the personalities and their emotions keeps the energy level high.

Director Anna D. Shapiro employs a passionate approach to the play. The anguish among the characters is outspoken, not muffled. The tears are torrential. There is no real physical action in the story and the only bit of violence takes place off stage at the end of the story. But the vividness of the personalities and their emotions keeps the energy level high.

There are 10 major figures in the story, each one etched with clarity and understanding. The Steppenwolf has assembled a multi-ethnic cast, adding African-American, Hispanic, and Asian actors into the conventional mix, but the ensemble meshes beautifully. Ora Jones (Olga), Carrie Coon (Masha), and Caroline Neff (Irina) are all splendid as three young women ground down by bad luck and inertia. They deserve better from life but they are left wondering if their suffering and disappointment has any meaning.

The satellite figures who revolve around the sisters are uniformly excellent. The most arresting character in the narrative is Solyony, the irrational enemy of the gentle, likable and ill-fated Baron Tusenbach (Derek Gaspar). Usman Ally gives Solyony a psychopathic edge that chills the viewer every moment he’s on stage. Dan Waller is terrific as Andrey, drenched in disappointment over his failure to become a professor and inwardly wretched that he has married a harridan who is making him a cuckold as she abuses his defenseless household. The adaptation doesn’t allow us enough familiarity with Natasha as she enters the Prozorov family, but Alana Arenas brings the vixen to life in all her viciousness, fueled by her inward knowledge that she isn’t in the same class as the cultured sisters and their circle.

There is also first-rate work from Scott Jaeck as Doctor Chebutykin, a man who tries to conceal his self-loathing as an incompetent physician under a coat of “what does it all matter” cynicism. Special praise goes to Yasen Peyankov, almost unrecognizable as Kulygin, the pitiable schoolmaster who bravely lives with the knowledge that his wife Masha loves another. B. Diego Colon makes a strong comic impression in the small role of Fedotik, a junior officer in the army. Two elder statespersons in area theater, Mary Ann Thebus and Maury Cooper, are fine as the Prozorov nanny and a comical watchman from the district council. Chance Bone rounds out the main characters in a nice turn as another army junior officer.

Todd Rosenthal’s set designs evoke the rustic provincial feeling of the play, largely through a large rectangular screen mounted at the rear of the stage that changes images as the action moves along. Donald Holder designed the evocative lighting, Rod Milburn and Michael Bodeen the sound, and Jess Goldstein the spot-on period costumes.

Todd Rosenthal’s set designs evoke the rustic provincial feeling of the play, largely through a large rectangular screen mounted at the rear of the stage that changes images as the action moves along. Donald Holder designed the evocative lighting, Rod Milburn and Michael Bodeen the sound, and Jess Goldstein the spot-on period costumes.

Like all Chekhov plays, the action in Three Sisters ends with journeys that will separate many of the characters from each other for life, including men and women who in a better world would have spent their lives together happily and productively. But that’s not Chekhov’s world. Most of the characters have wasted their lives, but they still retain a spark of bravery and dignity in their weaknesses, yearning for sparks of beauty and decency in their existence. They may be a woeful and exasperating lot, but it was a pleasure being in their company for 2 ½ hours at the Steppenwolf.

photos by Michael Brosilow

Three Sisters

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Steppenwolf’s Downstairs Theatre

1650 N Halsted St

ends on August 26, 2012

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit Steppenwolf

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago