BRIGHT LIGHTS ON A DIM HORIZON

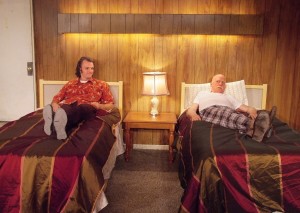

Two hit men wait in a shitty Vegas motel for the boss to give them a goddamn call. One of ’em (Leon Russom) is an all-business, no-shit guy on the verge of retirement; the other (Garrett Michael Langston) is a congenital fuck-up first-time gunman twitchin’ to get in over his head. Pretty soon the boss calls, and there’s a briefcase with heaters and stacks of cash and a photo of a broad, some hooker (Heidi James) that’s worth fifty grand to somebody, but dead, see?

This set-up sounds like you’ve seen it in a movie; this is often the case when a trope strains toward archetype, and archetypes, of course, are themselves merely in training to become mythology. Charles Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent share the master-and-apprentice assassin roles in Michael Winner’s mediocre The Mechanic; in Stephen Frears’ awfully good The Hit, it’s John Hurt and Tim Roth. In Martin McDonagh’s superior existentialist comedy In Bruges, Brendan Gleeson and Colin Farrell inhabit such similar characters and circumstances, and speak dialogue so similarly profane, that for the first half Nate Rufus Edelman’s Bright Light City seems as if it had been written under the influence of that picture. Well. Such a scenario is always at least faintly preposterous, but it’s what you do with it. The hit-man premise lends itself to life-and-death questions, issues of cosmic and universal relevance, and superficially it promises built-in drama. But this is almost never true: people who kill people for money have very little stake in the job except as a job, and pointing guns is not an inherently dramatic act, and psychopaths are about the most predictable folks you will ever meet in black and white.

This set-up sounds like you’ve seen it in a movie; this is often the case when a trope strains toward archetype, and archetypes, of course, are themselves merely in training to become mythology. Charles Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent share the master-and-apprentice assassin roles in Michael Winner’s mediocre The Mechanic; in Stephen Frears’ awfully good The Hit, it’s John Hurt and Tim Roth. In Martin McDonagh’s superior existentialist comedy In Bruges, Brendan Gleeson and Colin Farrell inhabit such similar characters and circumstances, and speak dialogue so similarly profane, that for the first half Nate Rufus Edelman’s Bright Light City seems as if it had been written under the influence of that picture. Well. Such a scenario is always at least faintly preposterous, but it’s what you do with it. The hit-man premise lends itself to life-and-death questions, issues of cosmic and universal relevance, and superficially it promises built-in drama. But this is almost never true: people who kill people for money have very little stake in the job except as a job, and pointing guns is not an inherently dramatic act, and psychopaths are about the most predictable folks you will ever meet in black and white.

Edelman wrote this piece when he was twenty-four, and it plays as might be expected: elementary, uncomplicated, underdeveloped. It’s a writing exercise, a necessary chore on the way to being a good writer more than it is a memorable script. Many of the situations and chatter are self-conscious enough to warrant the characters telling each other to stop using cliches. Soon it feels less like a motif than an excuse. In a related (lack of) development, he characters tend to have Elvis obsessions instead of personalities. We never do find out why this on-the-skids prostitute is worth more to these hit men than she’ll make in a year; and lacking any indication of larger business interests, the whole hit-man economy is underexplained to the point of foregone conclusion. It’s a mistake, given how much the writing concentrates on logistical detail. Only one of the characters has a backstory, and it’s as old as show business; this character provides a twist as old as melodrama; there are plenty of good lines, but overall the dialogue is promising rather than mature.

Edelman wrote this piece when he was twenty-four, and it plays as might be expected: elementary, uncomplicated, underdeveloped. It’s a writing exercise, a necessary chore on the way to being a good writer more than it is a memorable script. Many of the situations and chatter are self-conscious enough to warrant the characters telling each other to stop using cliches. Soon it feels less like a motif than an excuse. In a related (lack of) development, he characters tend to have Elvis obsessions instead of personalities. We never do find out why this on-the-skids prostitute is worth more to these hit men than she’ll make in a year; and lacking any indication of larger business interests, the whole hit-man economy is underexplained to the point of foregone conclusion. It’s a mistake, given how much the writing concentrates on logistical detail. Only one of the characters has a backstory, and it’s as old as show business; this character provides a twist as old as melodrama; there are plenty of good lines, but overall the dialogue is promising rather than mature.

The action takes quite a while to build, so the stuff the hit men do while they’re waiting around is less interesting than how the performers choose to go about it. Given characters this repellent, it’s up to the production to invest them with the humanity requisite to elicit an audience’s sympathy. This world premiere, staged by the author and Angie Scott, seems frankly not very directed at all except when Leon Russom is onstage. But that’s at least half the play, and those moments are really something.

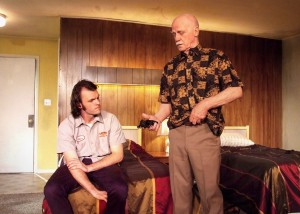

Russom provides physical business here that gets its own laughs, and packs a terse character with a moving, tangible, mysterious density of history and motivation. He executes stage generalship of the premium variety, expanding on the script in simple, effective gestures. When the play suggests that it was his button-down character’s idea to bring along on a serious job a guy you wouldn’t trust with your best pack of cigarettes, Russom plays him as if he’s already thought better of it. Russom knows so thoroughly what this play is about that he makes time seem important and valuable. For his part Langston throws himself into the energetic dumbness of his own sweet, irresolute, idiotic thug, and Heidi James is excellent as the woman-with-a-past, investing her character with stakes and depth the script demands but does not completely provide.

Russom provides physical business here that gets its own laughs, and packs a terse character with a moving, tangible, mysterious density of history and motivation. He executes stage generalship of the premium variety, expanding on the script in simple, effective gestures. When the play suggests that it was his button-down character’s idea to bring along on a serious job a guy you wouldn’t trust with your best pack of cigarettes, Russom plays him as if he’s already thought better of it. Russom knows so thoroughly what this play is about that he makes time seem important and valuable. For his part Langston throws himself into the energetic dumbness of his own sweet, irresolute, idiotic thug, and Heidi James is excellent as the woman-with-a-past, investing her character with stakes and depth the script demands but does not completely provide.

They do all of this on a well-aged, depressingly accurate motel room set by John McDermott – a set that must have infuriated the lighting designer when he first saw it, since the room has a ceiling. You don’t see a lot of ceilings onstage for this reason. Set guys love ceilings, because it’s one more giant canvas; lighting guys, not so much, since in small house, typically at least half the instruments hang over the playing area. Using a few practicals and a whole lot of front light, Luke Meyer handily provides morning, evening, and afternoon looks with nary an inappropriate shadow on the back wall. It’s a great physical environment, the sort of production value that elevates the material and the performances; as opposed to, say, an unreliable prop gun, an item that must also be listed among the objects on this stage. When a central prop – and in writing, what else is a gun? It’s a crutch even in real life – is a hindrance, there’s something amiss.

They do all of this on a well-aged, depressingly accurate motel room set by John McDermott – a set that must have infuriated the lighting designer when he first saw it, since the room has a ceiling. You don’t see a lot of ceilings onstage for this reason. Set guys love ceilings, because it’s one more giant canvas; lighting guys, not so much, since in small house, typically at least half the instruments hang over the playing area. Using a few practicals and a whole lot of front light, Luke Meyer handily provides morning, evening, and afternoon looks with nary an inappropriate shadow on the back wall. It’s a great physical environment, the sort of production value that elevates the material and the performances; as opposed to, say, an unreliable prop gun, an item that must also be listed among the objects on this stage. When a central prop – and in writing, what else is a gun? It’s a crutch even in real life – is a hindrance, there’s something amiss.

photos by Ed Krieger

Bright Light City

Los Angeles Theatre Center, Theatre 4

514 S. Spring St.

Thurs-Sat at 8 pm; Sun at 3 pm

ends on June 22, 2014

EXTENDED to June 29, 2014

for tickets, call 866-811-4111 or visit www.thelatc.org

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

This reviewer is obsessed with pointing out the clichés on the surface of “Bright Light City” while trying to convince the reader it is amateurishly written because Edelman was only 24 when he wrote it. Thank you for trying to do all the thinking for me, Mr. Rohrer, but I’ll let the play speak for itself.

Edelman’s dialogue, along with the pace and energy which the actors perform it, creates a complex trio of characters. I’d add a fourth character, Sam, to this list, even though we never see or hear from him, for he is always a looming presence—an ‘Uncle Sam’ figure.

The writing is only elementary in the sense that our hero, Wally, is a naive, disillusioned–albeit sweet and well-intentioned–young man. He is the play’s simplest character but he goes through the most complex emotions and discoveries on stage.

He is at a constant struggle between what his gut instinct tells him is right, and what he is forced to do when impulse takes over. We are left at the end wondering what will become of our hero.

Our reviewer here, however, is hung up on scrutinizing the narrative conventions Edelman uses as a tool to explore the themes about the darker aspects of humanity, morality, and autonomy (or lack thereof). However, this review fails to find any of this insight past the surface story of two hit men and a “take-home-girl.â€

I have to side with the reviewer on this one. While I really enjoyed the performances I thought the script fell short. Mr Edelman delivers a very seviceable script which the actors run wild with but it lacks the acerbic repartee and the deeper character development that really make the work of McDonagh or Tarantino sing.

Jason, I’d prefer we keep this discussion about the play instead of resorting to personal attacks.