THE UNDOCUMENTED

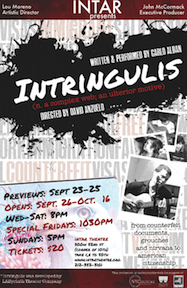

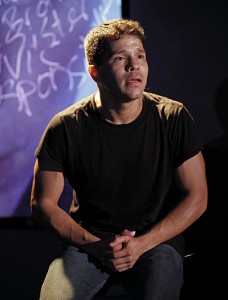

Intringulis, an autobiographical play written and performed by Carlo Alban, is now in production at Off Broadway’s INTAR. Stage and Cinema caught up with Carlo recently to discuss the evolution of the project and the plight of undocumented workers in the United States.

* * * * * * * * * *

Your play Intringulis, about the life of an undocumented immigrant, is relevant, timely, and eye opening. Many stereotypes were shattered; for example, how expensive it can be. I appreciated how you listed the expenses it cost your family. Not to mention the taxes taken out of your paychecks that will never come back to you. I was always under the impression that undocumented immigrants worked for money paid under the table.

Of course some do, but most often documents are required in order to obtain a job. And when taxes are taken out of paychecks, it’s not like tax benefits can ever be claimed. Most companies make a certain about of money, and they pay a certain number of employees, and they have to tell the government where their money is going. They can’t just pay people under the table. Like restaurants and other companies that depend on the cheap labor from undocumented workers, they have to prove to the government that they’re paying somebody; otherwise red flags pop up.

Of course some do, but most often documents are required in order to obtain a job. And when taxes are taken out of paychecks, it’s not like tax benefits can ever be claimed. Most companies make a certain about of money, and they pay a certain number of employees, and they have to tell the government where their money is going. They can’t just pay people under the table. Like restaurants and other companies that depend on the cheap labor from undocumented workers, they have to prove to the government that they’re paying somebody; otherwise red flags pop up.

But not because the documents are fake or forged?

The government knows. It’s an understanding. But they can’t go after everybody. The system would collapse.

Just yesterday, a nineteen-year-old girl and her mother were to be deported to Bangladesh, even though her father had a green card and she had lived here since she was two years old. Will the Dream Act eliminate such suffering?

The Dream Act has been on the board for a long time, and I’m not sure what its chances are of passing. Certainly, I hope it does pass, but we seem to be so split down the middle that it’s really hard to get anything done. And regardless, the Dream Act is still only amnesty. There has been a long history of amnesty; for example, when agricultural workers were needed, they created an amnesty for such workers and gave them a green card. But the Dream Act is not going to fix the system. It will help a few people who absolutely deserve it–hard working people with a lot of potential. All children have potential and of course they should be supported so they can become invaluable citizens and human beings, active and engaged, living out their potential. But the difficult issues for most undocumented immigrants will continue because this country is better off than most, and therefore people want to come here, provide for their family, and be a part of this culture that is exported all over the world.

As you say in your play, Mickey Mouse on a tee shirt with USA written underneath is a brand name most people want.

Yes, the way America exports their culture with such branding; it’s all very appealing. Most people are drawn here for a better life. So amnesty is great, especially the Dream Act, but it’s a band-aid cure for the larger issues that ultimately cause a lot of suffering. But at least for the children, it will provide them with a better life.

What did you miss out on as an undocumented child?

For example, my brother and I went to college. Not because we had documents but because we paid for it. In our college application, we checked the box that stated we were US citizens, and then they took our money and gave us an education. However, we were not eligible for student aid, grants, scholarships, or even student loans.

Your play also tells the heart-breaking story of your eldest brother who was left behind in Ecuador. Later, he was educated as a lawyer, then came here for a law internship. When he stayed longer than his visa permitted, he too became undocumented and went to work as a dishwasher.

There are plenty of professionals who leave their country and come here for better opportunities, but the reality of being able to work without the proper papers is very difficult and costly. I was incredibly lucky when I worked as a child actor on the TV series Sesame Street.

It sounds like the happiest of childhoods, and yet, as you say in your play, you lived in fear.

Of course, I was living the life my parents had hoped to give me, but we knew it could be taken away at any moment. When my father turned in a fake document to “Sesame Street” that had a different birthday than was just celebrated, I was so afraid that somebody would notice the mistake. And I waited. And waited. It’s hard to flourish as a professional without legal documents. You’re always waiting and wondering how much longer you can get away with it. There was an editorial in the Times a few months ago by a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, who admitted that he was living in hiding as an undocumented immigrant. And, like me, he was brought here as a child. Unlike me, however, he didn’t know he was undocumented until his teenage years. That must’ve been a shock. Even so, we are the lucky few. Most do not get to move forward in their profession; they are forced to accept low paying jobs.

Of course, I was living the life my parents had hoped to give me, but we knew it could be taken away at any moment. When my father turned in a fake document to “Sesame Street” that had a different birthday than was just celebrated, I was so afraid that somebody would notice the mistake. And I waited. And waited. It’s hard to flourish as a professional without legal documents. You’re always waiting and wondering how much longer you can get away with it. There was an editorial in the Times a few months ago by a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, who admitted that he was living in hiding as an undocumented immigrant. And, like me, he was brought here as a child. Unlike me, however, he didn’t know he was undocumented until his teenage years. That must’ve been a shock. Even so, we are the lucky few. Most do not get to move forward in their profession; they are forced to accept low paying jobs.

I was shocked to hear how many people took money from your family in the guise of helping you to become US citizens. And even more so that it took 12 year altogether.

There are a lot of lawyers and con men who prey on undocumented immigrants, and they’ll take your money, give you a false sense of hope, and then do nothing to help you. Maybe some of them mean well, but they make promises they can’t keep. You often hear the stereotype that undocumented immigrants cost the government a lot of money and they’re a drain on the system. This has not been my experience. Undocumented immigrants come here to work for a better life, and they work hard. They are hard working people who do it for their children. To me, it’s heroic. And it’s shameful to see how they’re treated and perceived.

How can this perception be changed?

The public view has changed throughout history depending on the needs of the land, the needs of businesses, the needs of government, and the needs of people. But the fact is, let’s not lose our cultural memory. We are a country of immigrants. Most Americans have immigrants somewhere in their past. And yet, it’s all too easy to forget, isn’t it? We need to remember our past, and we need to honor it.

And certainly, your play does just that. You have had the luxury of developing your play four different times: first presented at Labyrinth Theatre Company’s 2005 Summer Intensive, followed by a Barn Series reading at the Public Theater later that year, then followed at the Public Theater in 2007 and Redhouse Arts Center in 2009. The world premiere of Intringulis was a co-production between LAByrinth Theatre Company and Elephant Theater Company in LA in the fall of 2010, which was followed by a co-production with Southern Rep in New Orleans in the spring of 2011. How fortunate you’ve been to have all this time and attention to create this piece.

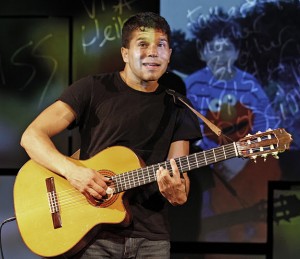

And thank God, because it’s not like I was a writer prior to this experience. I was primarily an actor, but as a company member at Labyrinth Theatre company, they are very encouraging in pushing you into other areas and trying new things.

At this point, is the script still evolving and developing?

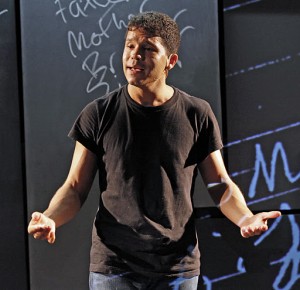

Yes, it continues to evolve. There are still things that I am learning. The process of development has not only been a process of clarifying the writing for the audience but also for myself. I am learning about myself through writing and performing this play. And every time I get in front of an audience, I often learn something new, and I try to incorporate it. Just yesterday, I improvised a moment; it was immediate, and the audience sensed it. I could feel everyone getting excited as if they knew this was happening for the very first time.

Though maybe the stage manager had a look of panic on her face. How has the play changed the most over the different stages of its development?

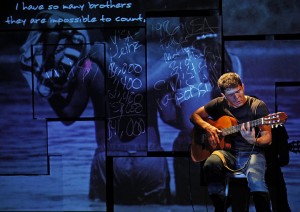

At the first public presentation, I still wasn’t a citizen, nor had I gone back to Ecuador. So the play ended in a very different place. Plus, there were different characters. I had a character that was a vigilante, who took it upon himself to police the Texas/Mexican border for undocumented immigrants. Later, my brother, Pacelli came into the story, at first in a small way, but now much larger. With this production at INTAR, I have a set that’s given me all these new elements to use and incorporate. Prior to this production, I was always on someone else’s set or just in an empty black box theater with only minor elements. We always had projections translating the lyrics, but not like this. It’s never looked this good before.

At the first public presentation, I still wasn’t a citizen, nor had I gone back to Ecuador. So the play ended in a very different place. Plus, there were different characters. I had a character that was a vigilante, who took it upon himself to police the Texas/Mexican border for undocumented immigrants. Later, my brother, Pacelli came into the story, at first in a small way, but now much larger. With this production at INTAR, I have a set that’s given me all these new elements to use and incorporate. Prior to this production, I was always on someone else’s set or just in an empty black box theater with only minor elements. We always had projections translating the lyrics, but not like this. It’s never looked this good before.

The set appears to be so simple and yet there are constant surprises with all that it does and brings to the play. And not just the set but this intimate theater space.

Yes, I feel so connected to the audience. This space is perfect for that.

It’s a very personal story, a homegrown story, an American story, built from the ground up. To experience this play in this space is a very meaningful theater experience. If I come back later in its run, will I hear more?

I don’t know. I know I have a lot to learn. I have so much to learn. About a lot of things. About everything. But I do want to keep writing, and I do want to keep trying to tell this story. So hopefully, I’ll find ways to do that.

You are very humble with such a positive outlook on life, despite all that you’ve been through and survived. Living in fear, hiding, never knowing when you might be caught could easily push others into a lot of negative aspects. Keeping that in check must have been difficult. I appreciated your acknowledging the angst in the scene with your dad when you blow up at him for getting your birthday wrong on a forged document.

The angst affected me, affected my relationship with my parents and siblings, and I knew I had to go there as much as I could. I wanted to be as honest as possible and as true as possible. I didn’t want to tell some sanitized version of my story. We’re all human, we all have faults, and we’re all struggling to make sense of all this. So the more honest I am, the more I hope people will connect. It all starts from truth and honesty, and the laughter and the sadness that follows comes from such honesty, too.

You dedicate this performance to your aunt Violeta.

Yes, back in Ecuador, she taught me to read and write. One of my earliest memories is of my aunt looking over my shoulder as I practiced writing my letters. Then we left Ecuador, and I didn’t see her for 20 years. She passed away this past September. She was 94 years old. She taught me to read and write, and now I wrote this play. That’s where it started. With her. My last memory of her is waving goodbye as my brother Angelo and I drove away in a taxicab. As she got further and further away, still waving, I thought to myself, is this the last time I’m going to see her? With immigration, an explosion happens, and we go away. We leave our families. We get separated. We disconnect. And we’re on our own. But at one time, we had these deep, strong relationships, and this love–and suddenly we’re so far apart from each other. I want to remember. I want to honor that.

Do you expect a reunion with your eldest brother, Pacelli?

I would love that. We haven’t talked in a long while. But part of it is because I’m here and he’s there. There hasn’t been a chance to reconnect. Whatever needs to happen between us, it’s not going to happen over the phone.

I would love that. We haven’t talked in a long while. But part of it is because I’m here and he’s there. There hasn’t been a chance to reconnect. Whatever needs to happen between us, it’s not going to happen over the phone.

When you were back, did you feel like a foreigner in your home country?

I didn’t feel like a foreigner, but it was clear to me that other people saw me as one. I felt at home in certain places; it felt familiar despite the fact that I was gone so long. But people smell it on you. I don’t know what it is, but they just know when you’ve been gone. You may be wearing jeans and a tee shirt, but they know you’ve been away a long time. Somehow, you carry it with you. I found being there very welcoming. It was beautiful. I loved it there. But I wouldn’t want to live there. I’m glad that I live here. The first thing my brother Angelo said to my parents when we got back was, “Thank you. Thank you for bringing us here. Thank you for giving us that.” Not because it’s a horrible place, but because we would not be who we are today without living here.

One of the scariest moments in your play involves your brother Angelo when he almost got deported because he turned 21 years old and was no longer a dependent.

It’s all so fragile. Most undocumented families are torn apart and separated from loved ones because they cannot find someone to help them or because they cannot afford the daily grind of the system. Most get lost in the system and are in hiding. Or deported. I’m not entitled to be here; I am lucky. I am so lucky. We are all so lucky to be here. We should all acknowledge that, whether we were born here or our parents or ancestors made sacrifices to come here. That’s what the last song in the play is about: being grateful for our lives.

photos by Carol Rosegg

Intringulis

written and performed by Carlo Alban

INTAR Theatre

scheduled to end on October 16, 2010

for tickets, visit http://www.intartheatre.org/