A LACK OF PHILOSOPHY

Elina de Santos’ production of David Ives’ 2008 New Jerusalem, The Interrogation of Baruch De Spinoza at Talmud Torah Congregation: Amsterdam, July 27, 1656 is the play’s west coast premiere, although L.A. Theatre Works presented the show last year.* This incarnation, however, is almost certainly the first to contain no moments designed to express the playwright’s intentions. Instead it offers long, featureless scenes clearly of De Santos’s creation, since the writing includes many opportunities for drama and humor that the director avoids with seemingly deliberate purpose.

The able West Coast Jewish Theatre cast does what it can to fulfill the promise of the material, but the evening lacks the spark of life. Stifled by their director’s mishandling of the script, the actors follow prescribed patterns of behavior and blocking, trying to break out of stagebound necrosis. The play’s mix of comedy and intellectual gamesmanship could be mounted successfully in either of two ways: as a drama with occasional humor, or, by a careful and attentive director, as a tennis match of wit and danger, a la early Tom Stoppard. But while the actors clearly see the jokes and drama in this script, De Santos ignores them, and much else that she should have noticed.

The able West Coast Jewish Theatre cast does what it can to fulfill the promise of the material, but the evening lacks the spark of life. Stifled by their director’s mishandling of the script, the actors follow prescribed patterns of behavior and blocking, trying to break out of stagebound necrosis. The play’s mix of comedy and intellectual gamesmanship could be mounted successfully in either of two ways: as a drama with occasional humor, or, by a careful and attentive director, as a tennis match of wit and danger, a la early Tom Stoppard. But while the actors clearly see the jokes and drama in this script, De Santos ignores them, and much else that she should have noticed.

The playwright bears responsibility for some of the difficulties here. A snapshot of one bad day in the life of the great Portuguese-Dutch philosopher Spinoza (Marco Naggar) – a merchant who faces ejection from the Jewish community for his inflammatory, revolutionary new ideas – the play mostly consists of unrefined, undisguised, didactic debate. This deliberation on the nature of God works much of the time, but Ives’ construction and character development is dubious.

The playwright bears responsibility for some of the difficulties here. A snapshot of one bad day in the life of the great Portuguese-Dutch philosopher Spinoza (Marco Naggar) – a merchant who faces ejection from the Jewish community for his inflammatory, revolutionary new ideas – the play mostly consists of unrefined, undisguised, didactic debate. This deliberation on the nature of God works much of the time, but Ives’ construction and character development is dubious.

An early scene at a tavern has the famously persuasive genius unable to convince Clara, a girl already in love with him (a miscast Kate Huffman), to stop arguing about religion. This absurdity, intended to set up a later development, would better serve its dramatic purpose of foiled expectations if it developed along exactly opposite lines.

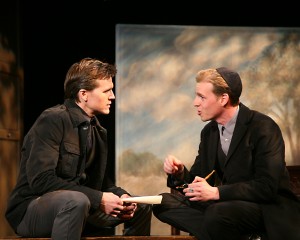

After becoming antagonistic at the excommunication trial, Spinoza’s friend, the painter Simon de Vries (Todd Cattell), suddenly defends the philosopher, with no warning or justification for his about-face. De Santos abets the playwright’s folly by making this one more opportunity to muffle any potential surprise, leaving Cattell to spout rhetoric while upstaged by several actors better positioned to draw focus.

After becoming antagonistic at the excommunication trial, Spinoza’s friend, the painter Simon de Vries (Todd Cattell), suddenly defends the philosopher, with no warning or justification for his about-face. De Santos abets the playwright’s folly by making this one more opportunity to muffle any potential surprise, leaving Cattell to spout rhetoric while upstaged by several actors better positioned to draw focus.

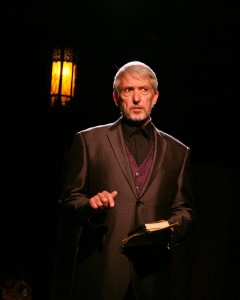

Similarly, at the moment the city’s chief rabbi Mortera (Richard Fancy) pronounces doom – the very climax of the show! – Spinoza’s de facto judge is directed to remain in the same posture he’s held for the past ten minutes. This might arguably be acceptable if it were an interesting stage picture, or if the director added some theatrical gesture; a peal of thunder would be too much, but how about a change of lighting? Someone falling to his knees? Sitting down? Let these instances of directorial inaction not be confused with understatement: this is no statement, no choice, apparently no notice of the basic necessities dictated by the writing.

Again, it’s not the actors’ fault. The elements of stagecraft have been banished from this stage, more effectively in fact than Spinoza was banished from his people. Both Ives and De Santos have assumed that the threat of excommunication held sufficient inherent drama to propel the proceedings, though neither writer nor director have offered any real reason for Spinoza to fear this fate (his half-sister Rebekah (Brenda Davidson) is a shrew; he hates business; he can’t marry the girl he loves anyway). In fact Spinoza lived quite comfortably in Holland for another twenty-odd years after his sentence, and in this production Naggar’s Spinoza exits smiling. An angry crowd for him to navigate, a thug with a knife, even a barking dog could have stood in for a potentially unhappy future. But no such threat exists. And while the bulk of the play is taken up by good actors speaking intelligent dialogue about weighty matters, this production is content to let that be that. It is as if the director said, “A good play is its own reward.” Well, it is, when you read it. When you stage it, though, you have responsibilities, such as framing the important instants that make up a story; otherwise your audience would be better served by a trip to the library than to the theater.

Again, it’s not the actors’ fault. The elements of stagecraft have been banished from this stage, more effectively in fact than Spinoza was banished from his people. Both Ives and De Santos have assumed that the threat of excommunication held sufficient inherent drama to propel the proceedings, though neither writer nor director have offered any real reason for Spinoza to fear this fate (his half-sister Rebekah (Brenda Davidson) is a shrew; he hates business; he can’t marry the girl he loves anyway). In fact Spinoza lived quite comfortably in Holland for another twenty-odd years after his sentence, and in this production Naggar’s Spinoza exits smiling. An angry crowd for him to navigate, a thug with a knife, even a barking dog could have stood in for a potentially unhappy future. But no such threat exists. And while the bulk of the play is taken up by good actors speaking intelligent dialogue about weighty matters, this production is content to let that be that. It is as if the director said, “A good play is its own reward.” Well, it is, when you read it. When you stage it, though, you have responsibilities, such as framing the important instants that make up a story; otherwise your audience would be better served by a trip to the library than to the theater.

*{Editor’s note: New Jerusalem was indeed presented by L.A. Theatre Works in 2011 at the Skirball Center with original cast member Richard Easton alongside Ed Asner. Actors were actually blocked and moved from microphone to microphone, something which is unnecessary to a radio audience. However, West Coast Jewish Theatre is the first fully-staged production sans scripts. Still, the definition of a “premiere” – according to all dictionaries – is the “first public performance or showing of a play.” Hence, when New Jerusalem was staged for radio broadcast before an audience, is it not, by definition, a West Coast Premiere? The term “Rolling World Premiere” was invented for playwrights to have their work tried-out by three different companies in the same year. If that play makes it to Broadway with alterations from the playwright, is it a Non-Rolling World Premiere? Since the word “premiere” is clearly being used as ticket-sales incentive, get ready for its ubiquitous use as a superlative for theatres (meaning something important or celebrated): “Cucamonga Premiere” or “Azusa Rep’s Premiere Since Our Last Premiere of a Rolling World Premiere” may not be far off.}

photos by Hope Burleigh

“New Jerusalem, The Interrogation of Baruch De Spinoza at Talmud Torah Congregation: Amsterdam, July 27, 1656.”

West Coast Jewish Theatre at the Pico Playhouse (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on April 1

for tickets, visit http://www.wcjt.org

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Responding to the Editor’s Note: The reading of a play does not equate to a full performance of a play. It absolutely does not.

I saw the production last night and it has restored my faith in the power of theater. After seeing a number of elaborately produced but ineffective and unaffecting highly-praised plays (Clybourne Park being the worst offender but a Shakespeare comedy set in Cuba was just as bad) this one had me engaged from the beginning. The philosophical-religious debate was fascinating (I will be reading more about Spinoza as soon as I can) and the actors made me care for them and their fate to the point of tears (I noticed others equally affected in the audience). I thought the staging was excellent – in sum, if the run weren’t ending tonight I would probably be planning to come see it again.