WHY DO WE HAVE WHY WE HAVE A BODY?

Every few years a vanity project comes along so appalling that one’s jaw hangs open for its entire running time, saliva connecting the lower lip to the floor in a single unbroken strand. The planets have to align very particularly for a travesty of this magnitude to take place:

*The show probably will be directed by its star, and that star ideally never will have directed before.

*A large amount of money has to be spent, and almost all of it has to be wasted.

*The opening date is usually pushed back at least a few weeks because of cast changes late in the rehearsal process.

*It’s not necessary, but it doesn’t hurt, if the script itself is an incoherent mess.

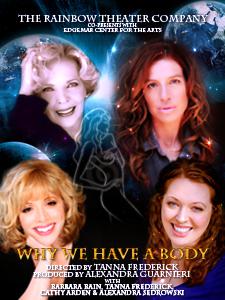

Tanna Frederick’s directorial debut and star turn in Claire Chafee’s 1993 Why We Have a Body fulfills every requisite. Do not see this play. Unless, of course, you are wont to see theater with the designation As Bad as It Gets.

What can you say about a show that repeatedly calls one of its characters a paleontologist only to have her refer to herself as a nuclear physicist? That hires a great jazz quintet and seats them onstage merely to provide sound effects? That sticks a nice old lady on a horse so high off the ground that she hurts herself upon dismount? I’ll tell you what you can say: You can say that that show is a bad, bad show.

What can you say about a show that repeatedly calls one of its characters a paleontologist only to have her refer to herself as a nuclear physicist? That hires a great jazz quintet and seats them onstage merely to provide sound effects? That sticks a nice old lady on a horse so high off the ground that she hurts herself upon dismount? I’ll tell you what you can say: You can say that that show is a bad, bad show.

How bad is this show? If this show were a dog, it would bite the neighbor’s kid in the face.

As an opening night bad-luck charm for this hapless production, quasi-celebrity Janice Dickinson swayed on her heels and inexplicably read out the cast list. The curtain had already been held for those twenty-five minutes, perhaps having waited for Ms. Dickinson, who when she did arrive charmingly introduced herself as “the girl who put the dick back in son.”

And then the show started.

I can’t say what it’s about, not for fear of giving away the plot but because there isn’t one. I can say that the play deals with the relationship of Lili, a lesbian gumshoe (Alexandra Sedrowski), and her sister Mary, a convenience store criminal (Ms. Frederick), and a not very imperative search for their absentee mother (Barbara Bain). Along the way, Lili begins a love affair with that scientist of disputed stripe, a married woman named Rene (Cathy Arden, who pronounces “genius” when she means “genus.”) To say more would be rank speculation on my part.

I can’t say what it’s about, not for fear of giving away the plot but because there isn’t one. I can say that the play deals with the relationship of Lili, a lesbian gumshoe (Alexandra Sedrowski), and her sister Mary, a convenience store criminal (Ms. Frederick), and a not very imperative search for their absentee mother (Barbara Bain). Along the way, Lili begins a love affair with that scientist of disputed stripe, a married woman named Rene (Cathy Arden, who pronounces “genius” when she means “genus.”) To say more would be rank speculation on my part.

As the missing mom, the lovable, lost-looking octogenarian Ms. Bain spouts mostly incomprehensible whimsy; she makes each appearance on a piece of set dressing: on (and painfully off) the aforementioned horse, on a bower, and once in a canoe ingeniously built onto a wheelchair. Unfortunately for Ms. Bain, the connotations of her childlike face leering from a wheelchair make that face frightening in its vacancy, especially once she starts throwing books out of the boat, books that thud on the concrete floor of the stage before the sound effect of a splash is heard; thud-splash, thud-splash; but it hardly matters. This production is uninterested in reality of any kind.

Asked “What was this show about?”, a person who has seen every rehearsal said, “That’s a difficult question.” Full of trite monologues that further no story and elucidate no theme, packed with wisdom like “a pound of butter is four sticks,” this is Womyn’s Theater run amok, the kind of play in which every man mentioned is a dud or a rapist. Ms. Chafee is the kind of playwright who relies on, instead of characters, banalities like one sister’s being a whiskey-guzzling private eye and the other an armed robber obsessed with Joan of Arc; instead of a story she leans on the cliché of the lost parent.

Asked “What was this show about?”, a person who has seen every rehearsal said, “That’s a difficult question.” Full of trite monologues that further no story and elucidate no theme, packed with wisdom like “a pound of butter is four sticks,” this is Womyn’s Theater run amok, the kind of play in which every man mentioned is a dud or a rapist. Ms. Chafee is the kind of playwright who relies on, instead of characters, banalities like one sister’s being a whiskey-guzzling private eye and the other an armed robber obsessed with Joan of Arc; instead of a story she leans on the cliché of the lost parent.

This inanity also plays on the premise (repeated in many Akiva Goldsman screenplays) that women have a magical mode of communication that defies all the established physics and logic of the rest of the story’s world; and of course this telepathy is a lazy writer’s code for talking on the telephone. And nobody would write two or three scenes in which women just sat and talked to each other on the phone, would they? Other than Claire Chafee? And if she did, nobody would read those scenes and stage them just that way? Would they? Other than Tanna Frederick?

On the subject of Ms. Frederick’s direction, the lady herself has said in print, “I never wanted to direct, but I’ve done six plays with director Gary Imhoff and five films with Henry Jaglom, so that’s equal to the best university training.” Her math (5 + 6 = Ph.D.) is not supported by the work she did on this show. But that she never wanted to direct? That much is very clear.

On the subject of Ms. Frederick’s direction, the lady herself has said in print, “I never wanted to direct, but I’ve done six plays with director Gary Imhoff and five films with Henry Jaglom, so that’s equal to the best university training.” Her math (5 + 6 = Ph.D.) is not supported by the work she did on this show. But that she never wanted to direct? That much is very clear.

So she doesn’t. That she dresses Ms. Bain, and herself, in a bewildering assortment of adorable costumes; that she has every actor perform in a state of heightened, presentational mania (except Ms. Sedrowski, who plays the whole thing whether concerned, seductive, threatening, or nurturing, with the same expression of smug complacency); that she has likely spent a fortune on Joel Daavid’s fascinating set and used each of its pieces only once or twice: this much can be said for Ms. Frederick’s direction. She has done these things.

How bereft is her direction? When a character shares family photos, the pictures are projected onto a wall with holes in it. The people in the pictures therefore have missing eyes or chins or foreheads, because the pictures are projected ONTO FUCKING HOLES. Characters in this show suddenly turn from one another and address the band, which sits on a level with much of the action, and which does double duty as a fax machine and angry traffic jam and, very occasionally, a band. The interaction among actors and orchestra could work, as a playful breaking of the fourth wall, but the fourth wall is the one toward the audience. Which wall does an actor break when she talks to the band? The wall of sound? (The talented band consists of Trevor Steer on keyboards, Kyle O’Donnell on saxophone, David Abrams on guitar, Cooper Apelt on bass, Robert Humphreys on drums and percussion.)

A novice director, having hired one of the best set designers in town to build a lovely series of architectural pieces, would do well to listen to him; it’s a safe bet Mr. Daavid advised against a literal interpretation for the set, and against configuring the airplane wing that juts out directly in front of a row of airliner seats, as if the passengers on this plane sat perpendicular to the normal seating arrangements on any airplane you’ve ever been on. Perhaps, knowing they were to be directed by Tanna Frederick, these passengers arranged their seats the better to be able to jump out of the plane.

Could this play be worse? Yes, it could. It could be longer.

Thud-splash.

I would be remiss not to note that other productions of this text have fared well with its target audience of alienated women and lesbians starved for any story remotely about them; but every audience deserves better than this, the worst possible production of a terrible play.

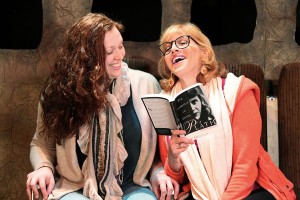

photos by Ron Vignone

Why We Have a Body

Rainbow Theater Company at Edgemar Center for the Arts in Santa Monica

scheduled to end on April 22

for tickets, visit http://www.edgemarcenter.org

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

It’s amazing that any production gets mounted in the first place, and sweet Jason has gone beyond the call of duty as a reviewer to make it clear to his followers in a subtle and delicate manner that the play was not to his liking. However, I do have to say, slashing the entire production to pieces, complain about holes in the wall as demonstrating ‘how awful the direction because of (ah-hem) FUCKING HOLES IN THE WALL’ (which was an artistic choice of Joel D.) and slamming every single actress squeezing every last ounce of insult you can get from each of them – is hitting below the belt. You are a lovely person Jason. Go try creating something. I’m sure it will be a million times grander than Why We Have A Body. And then you can sit high on your laurels as you thrash and tear apart some other artists’ hard work to the utmost detail including physical appearances of actresses who should be respected for their body of work alone and pronunciations which you are too intelligent to miss…Bravo Jason. You genius you, and genus of those who support the theatre and those who work for nothing to risk their asses every weekend. Aren’t we lucky we have you to tell us what you think.

You’re welcome. I agree that it certainly is amazing that your production got mounted.

But before you blame your shortcomings on someone else: I complained not of the holes (if you’re going to quote me, quote me correctly), but of the decision to project images onto them. Was that Mr Daavid’s idea, or yours?

Jason,

Knowing some of the performers in this piece as well as the venue, I just want to say that this is one of my favorite theatre reviews of all time! I stumbled on your “The worst review I’ve ever written” link and was glad I did. Thank you for trying to protect Ms. Bain AND the theatre-going public.

Arguing that a performer turning in a poor performance should be”respected for their body of work alone” is appropriate when that performer is your kid, playing on her grade school basketball team, or your mother on stage in a community theater performance of Gigi or some such tripe somewhere out in flyover country.

That standard, however, cannot and must not be abided by if and when one is, ostensibly, putting on a “professional” production, here in Los Angeles, and charging people money in order to be subjected to it.

Tanna’s complaint smacks just a little to much of a “why did you have to be so mean, we’re just girls” cop-out, attempting to engender sympathy and foment faux outrage among her sisterhood that a big bad man might have had the temerity to criticize their precious pet project.

Like a pet, however, it seems this production might have been best kept in the yard, and off the stage, where it might leave people cursing it after digging up the begonias, and looking for a curb to wipe their shoe off on.

A simple tilting up of the projector (which I [as set designer] did not install) would have made those holes not on people’s faces.