FANGS FOR THE MAMMARIES

Carson Kreitzer’s 2003 play Slither conforms to a certain category of American text: the women’s empowerment monologue extravaganza. Hallmarks of the genre include plotless, drama-free speeches of subjugation, delivered by female figures unfettered by character; a monologue format occasionally and inexplicably interrupted by thematically related scenes also lacking dramatic tension; and (should there be any male figures in the play’s landscape) rapacious and/or murderous and/or idealized fantasy-object male authority figures, usually fathers, husbands or priests. Kreitzer’s play features all of the above and stands as an excellent example of what this type of play may do even in the hands of a good director: bore anyone looking for stimulation or revelation about the human condition.

The play reflects blandly upon the history of men, women and serpents, sometimes going out of its way to entwine this lopsided triangle but never quite making a solid base for its pyramid. It does not help that Kreitzer has written her speakers as emblems or icons rather than real people; a little character goes a long way to involving an audience. The biblical Eve (Inger Tudor) blithely sews and smiles her way through the story of The Fall of (Wo)Man, a cataclysm one might expect to evoke more emotion from one of its primary participants; a Cretan priestess (Lina Patel) laments the coming Greek destruction of her civilization, about which she can do little but send visions forward in time to a snake-handling preacher’s wife (Teri Reeves), who interprets these dreams as a sign that her husband (Brian Slaten) may be trying to kill her with a snake. Whether he will or won’t murder her, and what she might do about it, constitutes the play’s single nod to suspenseful conflict.

Meanwhile the preacher’s wife’s inventor-grandfather (Tobie Windham) and Hootchy-Kootchy snake-dancer-grandmother (Amy Ellenberger) hand out folksy wisdom predicated on the idea that epoxy, a glue made from two separate elements bound together, will save a marriage. As yin-yang metaphors go, this one feels particularly awkward, especially since the play cannot decide whether the slithering snakes in the lives of these women are a stand-in for aspects of male personality or a separate entity altogether. It also fails to reconcile its angst about men: it can’t live with them, and it can’t cut their heads off with a shovel.

Meanwhile the preacher’s wife’s inventor-grandfather (Tobie Windham) and Hootchy-Kootchy snake-dancer-grandmother (Amy Ellenberger) hand out folksy wisdom predicated on the idea that epoxy, a glue made from two separate elements bound together, will save a marriage. As yin-yang metaphors go, this one feels particularly awkward, especially since the play cannot decide whether the slithering snakes in the lives of these women are a stand-in for aspects of male personality or a separate entity altogether. It also fails to reconcile its angst about men: it can’t live with them, and it can’t cut their heads off with a shovel.

Casey Stangl, who last year did such a good job directing a straightforward Peace in Our Time at Antaeus, shows a shaky hand staging Slither in a non-traditional manner at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery’s former Masonic Lodge. Placing the audience in straight-backed wooden chairs facing one another more than any of the action, Stangl makes playgoers crane their necks to see actors who might be anywhere in the room except those easily seen. Occasionally my head was required to twist simultaneously to the side, to the rear, and to the ceiling. I’m all for involving the audience in the action, but our action here is not that of the show; it’s our attempt to watch the show. There’s a difference. These attempts to physicalize the excitement missing from the source material might be worth it if there were anything dynamic for the paying participant to see once his face was aligned with the players, but the action remains static. That’s not quite true: after an hour and a half someone pulls a gun she doesn’t fire, at once breaking Chekhov’s rule and unintentionally subverting the anti-phallic thesis of that particular storyline. One might appreciate this accidental absurdism as one of the evening’s few opportunities to see into the intentions of the playwright, although, again, I doubt that this was what she would have liked me to notice. Alas, her intentions in this play remain as obscure as the show is dull.

Casey Stangl, who last year did such a good job directing a straightforward Peace in Our Time at Antaeus, shows a shaky hand staging Slither in a non-traditional manner at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery’s former Masonic Lodge. Placing the audience in straight-backed wooden chairs facing one another more than any of the action, Stangl makes playgoers crane their necks to see actors who might be anywhere in the room except those easily seen. Occasionally my head was required to twist simultaneously to the side, to the rear, and to the ceiling. I’m all for involving the audience in the action, but our action here is not that of the show; it’s our attempt to watch the show. There’s a difference. These attempts to physicalize the excitement missing from the source material might be worth it if there were anything dynamic for the paying participant to see once his face was aligned with the players, but the action remains static. That’s not quite true: after an hour and a half someone pulls a gun she doesn’t fire, at once breaking Chekhov’s rule and unintentionally subverting the anti-phallic thesis of that particular storyline. One might appreciate this accidental absurdism as one of the evening’s few opportunities to see into the intentions of the playwright, although, again, I doubt that this was what she would have liked me to notice. Alas, her intentions in this play remain as obscure as the show is dull.

photos by Tom Ontiveros

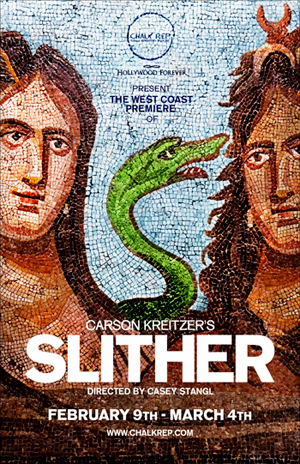

Slither

Chalk Repertory Theatre at the Masonic Lodge of the Hollywood Forever Cemetery (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on March 4

for tickets, visit http://www.ChalkRep.com