DESIGNING THE FUTURE

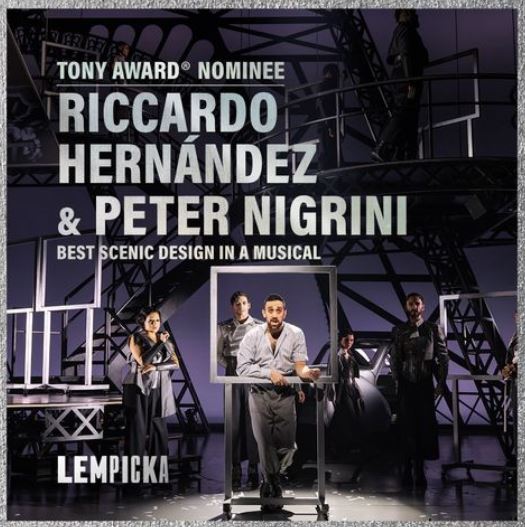

Tony-nominated set designer for this season’s Lempicka, Riccardo Hernández also designed Suffs. Other Broadway productions have included The Thanksgiving Play, Jagged Little Pill, Indecent, Porgy and Bess, Caroline, or Change, Bring in ’˜da Noise/Bring in ’˜da Funk, and the original Parade. An international designer of operas, plays, and musicals, he’s also the co-chair of the department and head of set design (hand-picked by former head Ming Cho Lee) at the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale. Stage and Cinema’s Gregory Fletcher recently spoke with Mr. Hernández about his busy life and bustling career.

GREGORY FLETCHER: Congratulations on your Tony nomination for your wonderful set design for Lempicka. You’d worked with director Rachel Chavkin before on The Thanksgiving Play by Larissa FastHorse. You’ve collaborated a few times, yes? When was the first?

RICCARDO HERNÃNDEZ: At the New York Theater Workshop on the Caryl Churchill play Light Shining in Buckinghamshire.

Light Shining in Buckinghamshire at NYTW; scenic design by Riccardo Hernández (Joan Marcus)

FLETCHER: Is that the primary way you get hired? By repeat business of former directors you’ve worked with?

HERNÃNDEZ: That and word of mouth. Only because I’ve been going at this since 1992. I started with Suzan-Lori Parks when I was a grad student at Yale. In my third year, I designed her play The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World, and from then on, people just started calling. I had a long-standing collaboration with George C. Wolfe, and to this day I have a relationship with the Public Theater. I just think it’s a question of sensibility and people gravitating to the kind of work I do.

Suzan-Lori Parks and Riccardo Hernández on the set of Sally & Tom

FLETCHER: Is there an order to hiring designers? Meaning, does the set designer get a say on who the other designers are?

HERNÃNDEZ: It all depends on the director. When I work with Rachel, she knows who she wants. Sometimes, we talk about who might be an interesting young costume designer or recent graduate in lighting, especially for working Off-Broadway, but for the most part, the directors know who they want. If that designer isn’t available, then they may ask me for a recommendation.

The Cast of Lempicka (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

FLETCHER: Were any of your collaborations with Lempicka first-timers or had you worked with all the designers before?

HERNÃNDEZ: With Lempicka, we had done it a few times before. When we did it at Williamstown, it was the first time that I had worked with Bradley King’”a fantastic lighting designer. And when we did it here on Broadway, it was my first time with Paloma Young [on costumes]. When you have new people in the team, you take the time (along with the director) to show where you are in your designs, what the ideas are that are being discovered so that they can weigh in on the collaboration.

Scale Model for Lempicka (courtesy Riccardo Hernández)

FLETCHER: Working on Lempicka must’ve been a very special design, mainly because she too was an artist, and there must have been an interesting discovery for you on how much or how little of her own art to show. How did you discover that fine line?

HERNÃNDEZ: Because we had the opportunity to work on Lempicka multiple times, the first time we did it was a bit inspired by Lars von Trier’s film Dogville. It was like this cinematic studio with very harsh silhouettes and old fashion TV rolling lights onstage, almost like a performance’”very, very Brechtian. Then when we got into the La Jolla [Playhouse] designs, which ultimately got cancelled due to the pandemic, we started getting very granular with the environment’”the physical visual environment that we needed to tell the story that time around.

Poster of The Man with a Movie Camera by The Stenberg Brothers, 1929

When I started looking at the world in which art was changing at that time, I was looking at the Bolshevik Revolution Art 1917. In the early days, they had incredible propaganda posters by the Stenberg brothers, [Vladimir and Georgii]. And then, there were the beginnings of constructivism with Meyerhold and the artist Popova and the early work of Sergei Eisenstein’s films. I was also deeply inspired by the work of Moholy-Nagi and the sculptures of Naum Gabo. In fact, we used Moholy-Nagy’s short film “Shadow Play” in our projections. The deeper I got into that, I was looking at the work of Marinetti, who wrote The Futurist Manifesto, which then led to researching Cubism and all that was happening in Paris at the same time of the post-Soviet Revolution. Which then of course led me to Fascism because of what was happening in Italy and Germany, and how that propaganda worked. How did that relate to what the Bolsheviks were doing? It’s very interesting that they are similar because of the scale, the way they depict the human bodies.

George Abud and the Cast of Lempicka (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

And then we have Lempicka who is thriving in the middle of all this, but also in completely difficult political times. There’s a sense that her Art Deco figures seem to be stretching and exploding off the canvases. I think it was in the zeitgeist of what was going on at the time. It all influencedo everything that we did. So, to answer your question, we made the decision not to show her work until the very end. We wanted to create more than an installation that had the inspiration and vibrancy of all the things I just discussed, with levels of Meyerhold, supported by large architectural truss angles rising up into the flies. Nothing is straight because Matt [Gould’s] music is very operatic and kinetic and within that, we have projections showing snippets of her paintings. But we didn’t show actual finished paintings until the very end of the piece. And so that’s how we dealt with her artwork itself. Because of the pandemic, we literally had time to consider and reconsider, think and rediscover what we wanted to create.

The Cast of Lempicka (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

FLETCHER: Something good to come out of the pandemic. Lucky you.

HERNÃNDEZ: Absolutely. Nothing is really ever finished. Obviously, you have to make choices, but up to the point of making specific choices, as I learned from Ming Cho Lee, “There is always room for better design or rediscovery.”

FLETCHER: But is there a point you can stop? Stop seeing details to improve and just letting it be? Is it when everything is built onstage?

HERNÃNDEZ: Hopefully before that. Eventually, you’re gonna have to show the work to the producers or the artistic directors prior to making the final decisions. And leading up to that point is when we keep playing. Right before the designs were due for Lempicka, I was working with Rachel on another production at the Vineyard Theater [Scene Partners]. We spent much of our tech time doing at least seven or eight different variations of what ended up onstage. At one point, I had four or five different levels. There was one version that felt like you were inside the Eiffel Tower. The producers thought it was all very exciting, but ultimately chose another. So, yes, there always comes a point in time when choices are made, and we march on.

Natalie Joy Jonson and the Cast of Lempicka (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

FLETCHER: How much time is that before you’re onstage?

HERNÃNDEZ: It depends when the theaters are available for Broadway shows. When I did Jagged Little Pill at ART [in Boston], that was a very big show. After the run, there weren’t any Broadway theaters open that were big enough to fit our design. We had to wait one season before getting The Broadhurst Theater. It depends on theater availability. The producers and the director tell you, “We’re coming to Broadway,” but they can’t always tell you when. At the Metropolitan Opera, for example, I designed Florencia en el Amazonas last year. Sometimes, you have up to two years to work on a project or three, because opera works much differently than commercial theater. At a regional theater, you usually have a year in advance or a little bit less. For Off-Broadway, sometimes they’re waiting for a star to sign on before they say yes to the project. Which means, you might have very little time once everything is set in motion, so it all varies. Ideally, you want as much time as you can have to get with the director and the rest of the design team. On Broadway, Lempicka was fast. I would say we were seriously delving into it in November and during the summer I had only done my first sketches and talking about ideas, working on the model. I had the architectural model of the Longacre Theater by August and final drawings by December.

Florencia en el Amazonas at the Met (Ken Howard)

FLETCHER: How much time is needed at a shop to build it?

HERNÃNDEZ: The drawings were finished right before Christmas, and then Neil Mazzella at Hudson Scenic started drafting to build the show because much of it was extremely difficult. I don’t know if you recall that we had very little support beams in many of the structures, so the engineering took a lot of time. They began working right away and started the build by the beginning of the year.

FLETCHER: When did it show up onstage?

Eden Espinosa in Lempicka (Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

HERNÃNDEZ: Loading in in February and by the top of March we were on stage. [First preview was March 19.] In the middle of that, I had Suffs. I was going back and forth between The Longacre Theater and The Music Box. Thank God the Lempicka producers agreed to let Hudson Scenic build the sets because I could just go to one shop and see both shows in progress as opposed to running around to multiple locations.

FLETCHER: On one hand, working on two shows sounds heavenly. But on the other, it sounds exhausting. But it must be a good exhaustion, no?

HERNÃNDEZ: I was also working on a Carmen at the Glyndebourne Festival in the UK [directed by Diane Paulus].

Carmen at Glyndebourne Festival Opera (Richard Hubert Smith)

FLETCHER: Do you ever say, “No. Not now.”

HERNÃNDEZ: You want to be able to work on a variety of things like Carmen, The Screens in Paris, and two Broadway musicals. It’s very exciting.

FLETCHER: I’m sure that kind of variety must fuel you with flowing creative juices. Which do you prefer between operas, plays, and musicals?

HERNÃNDEZ: I love theater, but where I come from is opera. My father was an opera singer. From my earliest memories in Cuba, he was already bombarding me with opera and classical music. And then when we moved to Argentina (around six years old), he then took me to the Teatro Colón Opera House literally every night. In fact, the very first opera I saw (I still have the program) was Lucia di Lammermoor, designed by Ming Cho Lee. Later, when I realized he taught at Yale, I knew if I wanted to become a set designer, I had to study with Ming. In my interview with him, I told him that I saw the production in 1972. He smiled and said, “Oh, my God, it was not good!” But I was a child; what did I know? I told Ming it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

FLETCHER: What year was it when you moved to Argentina?

HERNÃNDEZ: I would say’¦1971. Then we left right before the Falklands War with England. It was pretty chaotic in Buenos Aires because of the military coup, the civil war, and the disappearances. Because of our Cuban background, my father and mother felt that we should get out. And we came to the States in 1980. Miami, Florida, because there was a large Cuban community there.

FLETCHER: Thank God you were able to get out. Did you know how bad it was getting as a teenager?

HERNÃNDEZ: I remember tanks rolling down the streets of Buenos Aires the day of the coup in 1976, which is a city like Paris. Machine guns blasting in the middle of the night. Bombs exploding. It was surreal.

Soldiers in front of the presidential palace in Buenos Aires at the beginning of the 1976 military coup (AFP/Getty Images)

FLETCHER: But what an amazing cultural upbringing you had there. And what a remarkable dad you had! Lucky you. Do you have many memories from Cuba?

HERNÃNDEZ: We left when I was five. I remember the music my father would play. But the memories I have of Havana are very foggy. There were these very depressing black-and-white Russian cartoons’”all political’”the feeling was very severe, not funny. Indoctrinating the young with all the propaganda. The anti-Yankee things. This is a 5-year-old remembering, mind you. It was extremely political, and my father’s father, my grandfather, had fought alongside Fidel. My mother was Argentinian and believed in communism, and my father hated it. I grew up with that juxtaposition between communism or Utopia, and then the reality of what it is to be in the arts. My father always believed in the arts and soon enough, when he could talk to me, he said that in a country like Cuba or the Soviet Union, you cannot express yourself fully because everything is controlled. In a very unconscious way, it was a complex time, I’m sure, with buried PTSD. There are things I don’t remember that I know were very difficult, but by the time we got to Argentina, the world had changed. I was going to the opera with my father, who also loved literature. He introduced me to so many books, all very influential for my life in the arts. I love reading, so he gave me (when I was eight) all of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories and essays, (translated by Julio Cortázar into Spanish; I still have those books), which led to Julio Cortázar’s short stories and a lot of reading of South American literature: Jorge Luis Borges, Horacio Quiroga’s short jungle stories, and my discovery of Charles Baudelaire’s Flower of Evil. That changed something in me; how could it not? So much of my creativity was mysterious, loopy, very dreamy, nothing very realistic or naturalistic, which has influenced the way I see theater and embody my kind of sensibility.

Scale Model for Lempicka (courtesy Riccardo Hernández)

FLETCHER: When did plays come into your life?

HERNÃNDEZ: In Argentina. The first one my father took me to was Oedipus. Another production, I remember seeing a man dressed in black, sitting in a chair, smoking opium. It was a play about Poe called Israfel. That would have been like an Off-Off-Broadway production in New York.

FLETCHER: When did musicals come into your life?

HERNÃNDEZ: Not until we moved to Miami. I was not well versed at all.

FLETCHER: What was your first Broadway musical?

HERNÃNDEZ: 42nd Street in the 1980s’”the original production with Robin Wagner sets, so fantastic. Then I saw a few more when I was at Yale. When I started working with Suzan-Lori Parks, George Wolfe had become the new artistic director at The Public Theater, and he came to see the play and said he wanted to produce it. That next season, he called me to design Blade to the Heat, which led to The Tempest that moved to Broadway. My first musical to design was Bring in ’˜da Noise/Bring in ’˜da Funk with George directing.

(courtesy Riccardo Hernández)

FLETCHER: Who were your mentors?

HERNÃNDEZ: At that moment in time, Robin Wagner. No one did musicals and movement like him. My next musical was Bells Are Ringing, and then Caroline, or Change. I was much more well versed by that point. And with Hal Prince when I did the original Parade right after Noise/Funk, that was a huge lesson because walking into his office, he had stacks of Plexi boxes with models from Little Night Music, Company, and many more, I was very young, not even 30. Every time I suggested an idea, he’d say, “Oh, I’ve done that, let’s think of something else.” Well, I knew I had to dig deep-deep-deep into my instincts, which, thank God, I was not afraid to do.

With so many friends, I’ve learned lots. Yeah, tons. They don’t do musicals like they used to anymore. Those big musicals with tons of movement and scenery, it’s just a different world now, right? I was lucky to see the end of that era with Robin Wagner, Doug Schmidt, Tony Walton, David Mitchell, and John Lee Beatty who taught me for one semester. Once in grad school, I was looking at a lot of theater, discovering the European side of things. I discovered Pina Bausch. She blew my mind. And to finally see onstage at BAM the work of my idol Ingmar Bergman, I realized there was another kind of theater that was different. I embodied both sides because I’m still working in Europe, and I love that kind of versatility. I am blessed that I work in Europe and create challenging work that would be very difficult to produce in the US. and seeing the work of Romeo Castellucci and Angélica Liddell at Avignon shook me to the core.

The other critical mentor I had was Robert Woodruff who taught me not to be afraid to create ugly things if the plays demanded it. He told me once, “Stop beautifying!” “There is beauty in the ugly!” He single-handedly changed the way I see things. To this day I connect with rough difficult material. I miss him very much. When I’m fortunate enough to do something on Broadway, I try to bring some of the other aesthetics that are happening in Europe. Case in point, Lempicka. I couldn’t have designed it like I did this season if it were 10 years ago. Because it doesn’t look like your typical Broadway musical. There’s a new breed’”a new generation of amazing directors like Rachel Chavkin, Diane Paulus, Arin Arbus, and what’s amazing is that they’re mostly women.

FLETCHER: As witnessed recently at The Tony Awards.

HERNÃNDEZ: That’s exactly right. And that was wonderful to see.

FLETCHER: Despite ten or so nominated female directors in the past, it wasn’t until 1998 that Julie Taymor won for directing the musical The Lion King, and Garry Hynes won for directing the play The Beauty Queen of Leenane. Both directing prizes went to women. And at last night’s Tony Awards, Julie Taymor’s niece, Danya Taymor deservedly won Best Director for the musical The Outsiders.

HERNÃNDEZ: That’s right. The Outsiders is yet a new sensibility. I think it’s striking and paving the way for a new way of seeing musicals, especially from my teaching point of view. We can train our students with traditional concepts of design, but then they can work and try daring new things. Knowing the past traditions allows you to break free and create new worlds and be bold. To use Woodruff’s phrase: “Being irreverent.”

Scale Model for Suffs (courtesy Riccardo Hernández)

FLETCHER: I saw Suffs Off-Broadway last season, and then I recently saw it again on Broadway. I couldn’t help but notice how different the two productions were. When I compared my Playbills, it looked like the entire female design team had been replaced for Broadway with men. Am I correct?

HERNÃNDEZ: It is correct. But my understanding is that it was based on scheduling conflicts. The original designers weren’t available at this specific time. When Leigh [Silverman] called and asked me to join the team, I jumped at the opportunity.

Hannah Cruz as Inez Milholland with the Suffs Company (Joan Marcus)

FLETCHER: Did she give you the freedom to make it your own or was she asking you to recreate a similar design?

HERNÃNDEZ: I had not seen The Public Off-Broadway production. I saw photos, and I’m a big fan of Mimi Lien, but Leigh told me that she wanted something completely different. “Let’s rethink the whole thing; there’s going to be a new script; I want you to come to the workshop.” What impressed me right away was how fluid we could be, because a lot of the transitions are extremely fast. For example, going from the office to the big reveal of Inez on the horse, and back to the office and then to the White House. I knew that the key to the design had to be fluidity, and within that, having a conceptual idea of a massive, monumental classical architecture that dwarfs these incredibly forceful women. I first started designing the march down Pennsylvania Avenue because I knew I should capture that in a grand operatic way. Some people may call it a minimalist moment, but it’s not. It’s open space with monumental Corinthian columns moving within a Neoclassical cornice inspired by the Supreme Court facade, framing this magical group of women. And with Inez up on the horse, I knew if I could get that moment right, I could then work backwards and create the intimate scenes. It’s my homage to Giorgio Strehler’s work. I’ve never told this to anyone!

Scale Model for Suffs (courtesy Riccardo Hernández)

FLETCHER: Stage and Cinema thanks you. We’re honored. And Giorgio Strehler’s La Tempesta remains one of the most powerful productions of my life! Hearing you use “fluid movement” to describe your work with Suffs, it’s precisely the magic of that production. Smooth, easy, and grand’”Robin Wagner would be proud! I loved all the woodwork paneling you used, the white classical columns, and when you introduced color in the president’s office, I gasped at the red’”it was so beautiful. As well as the blackness and the one row of windows in the prison. I really appreciated the balance of simplicity and spectacle.

HERNÃNDEZ: I usually don’t say this, but in this case I will. I’m glad I didn’t know anything more about Suffs. I had to learn a brand new musical very fast and that’s tricky, and of course Leigh and Shaina knew it backwards and forwards. I was catching up with the changes, but beyond that, I was happy that I could create something completely different.

Tsilala Brock and Grace McLean as Dudley Malone and President Woodrow Wilson in Suffs (Joan Marcus)

FLETCHER: What’s next for you? What’s coming up?

HERNÃNDEZ: I’m doing The Merchant of Venice in Edinburgh, Scotland. Then I’m going to be working on a new production in France. I don’t know the title yet. It may be called Buchner’s Danton’s Death or a play by Yukio Mishima. I have a whole bunch of things on the table, two of which are musicals. And I’m praying that Sally and Tom by Suzan-Lori Parks moves to Broadway, even as a limited engagement.

Adjudicating the Design/Tech Awards at SETC, 2019 (Joan Marcus)

FLETCHER: Do your students at Yale ever see you in person or is it all on zoom?

HERNÃNDEZ: I’m always in New Haven. I co-teach with Michael Yeargan. And when Michael’s working, I’m there in class. And vice versa. Or I tell Diane, Rachel, or Leigh that in the mornings I’ll be teaching in New Haven, and then I’ll take the train in and stay for the 10-out-of-12, and back and forth. If something’s going wrong or I need to be here, then of course I change my schedule a little bit, but I hate not being there in person. I have done my classes by zoom, but 90% of the time I’m there in person.

Co-chair Michael Yeargan and Riccardo Hernandez with design class. Yale School of Drama 2018 (Joan Marcus)

FLETCHER: Clearly, you have a lot of energy and focus. Your students are very lucky to have your dedication. I’ve worked with celebrity “professors” who aren’t as committed and giving.

HERNÃNDEZ: Yale is a profoundly special place to me. Because Ming Cho Lee called me to teach there and to lead with Michael. Now, I’m the Co-chair of the department and head of set design. And meeting Ming Cho Lee through his design when I was 6-7 years old, that means a great deal to me too. There’s a lot of history and legacy to preserve while we move into the future.

# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #

find Gregory Fletcher at Gregory Fletcher, Facebook, Instagram,

and on TikTok @gregoryfletcherNYC.

![Post image for Interview: RICCARDO HERNÃNDEZ (Scenic Designer for Broadway’s LEMPICKA [Tony Nomination] and SUFFS)](https://stageandcinema.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Riccardo-Hernandez-7-copy-3.jpg)

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Gregory,

Thank you for an enlightening interview. Like you and Hernandez, I’m also a major fan of the late Giorgio Strehler’s work.

I was in La Scala two weeks ago to see a revival of Strehler’s 1980 Falstaff production. The stage was awash in rustic splendor, a barnyard rendered with the grandeur of an operatic canvas—-its Northern Italian farmstead basking in a honeyed, pastoral glow. Sir John Falstaff’s lodgings, a barn in all but name, exuded the same golden light, filtering dreamily through latticed panels, as if nature itself conspired in his indulgences. But it was in the midnight forest of Act III that the production truly conjured its magic—-a spectral haze curling from the stage floor, a moon suspended like an operatic illusion, its ghostly sheen casting an otherworldly spell.