CUT THE PRE-CURTAIN SPEECH!

If any evidence is needed to prove that Los Angeles is – as a theater town – still somewhat provincial, I present, for your delectation, the pre-curtain speech.

- At the Odyssey production of Adding Machine: A Musical, Ron Sossi encouraged the audience to tell their friends about it…whether they liked it or not.

- At the Blank Theatre’s The Cradle Will Rock, Daniel Henning hawked the cast album of the 1994 production and assured us that this new edition was filled with the most talented company of actors he has ever worked with.

- Michael Michetti pointed out at the opening of Camino Real that if the script had come to them without a title and without Tennessee Williams’s name on it, it was still Boston Court’s kind of play and they would have felt compelled to do it under any circumstances.

- The woman introducing Women in Shorts literally gushed with excitement about the fabulous time we were going to have and apparently nobody told her that such praise was as close to a kiss of death as you can get, unless, of course, the evening did turn out to be, indeed, fabulous.

If I had not seen the Next Theatre rendering of Adding Machine in a production which brought to stunning life, under David Cromer’s pitch-perfect direction, every possible value of the work of its creators – composer Joshua Schmidt and his co-librettist Jason Loewith as well as Elmer Rice, whose brilliant expressionist play was the source – I would not know what to make of this chamber musical. Ron Sossi is to be admired for appreciating good work, but it is time to point out that, in the theater, a show is made memorable by its execution and presentation and not just by its intrinsic worth. If the greatness of a play is enough, then every production of a great play would automatically make it worth your while; but, as everyone knows, there are productions of Hamlet or Death Of A Salesman or [ you fill in the space with your favorite classic] that are execrable.

If I had not seen the Next Theatre rendering of Adding Machine in a production which brought to stunning life, under David Cromer’s pitch-perfect direction, every possible value of the work of its creators – composer Joshua Schmidt and his co-librettist Jason Loewith as well as Elmer Rice, whose brilliant expressionist play was the source – I would not know what to make of this chamber musical. Ron Sossi is to be admired for appreciating good work, but it is time to point out that, in the theater, a show is made memorable by its execution and presentation and not just by its intrinsic worth. If the greatness of a play is enough, then every production of a great play would automatically make it worth your while; but, as everyone knows, there are productions of Hamlet or Death Of A Salesman or [ you fill in the space with your favorite classic] that are execrable.  What we have here is a failure of both nerve and imagination on Sossi’s part. He seems to have looked upon the whole thing as if it were some recently discovered and decidedly second-rate musical by Bertolt Brecht. He has even encouraged the sort of mannered performance by Clifford Morts in the central role that would be right in a revival of The Threepenny Opera, but is hopelessly overwrought and misguided here. The invention and the range of the score has been given a numbingly monotonous reading under

What we have here is a failure of both nerve and imagination on Sossi’s part. He seems to have looked upon the whole thing as if it were some recently discovered and decidedly second-rate musical by Bertolt Brecht. He has even encouraged the sort of mannered performance by Clifford Morts in the central role that would be right in a revival of The Threepenny Opera, but is hopelessly overwrought and misguided here. The invention and the range of the score has been given a numbingly monotonous reading under  Alan Patrick Kenny’s musical direction, excepting, of course, the beautiful rendition of “I’d Rather Watch You” by the remarkable Christine Horn. The world of the piece is severely short-changed, particularly in the uninspired set design of Charles Erven, and most of all in his flavorless view of heaven’s Elysian Fields, pictured here as a set of billowing sheets that suggests nothing but, well, a set of billowing sheets. All that survives is Rice’s play, a still timely tragedy about a man who, after twenty-five years of service, expects a promotion, but who is instead fired and replaced by a machine and who kills his employer and finds moral redemption only after his death by execution. They should have done the play. The musical version is still awaiting production in Los Angeles.

Alan Patrick Kenny’s musical direction, excepting, of course, the beautiful rendition of “I’d Rather Watch You” by the remarkable Christine Horn. The world of the piece is severely short-changed, particularly in the uninspired set design of Charles Erven, and most of all in his flavorless view of heaven’s Elysian Fields, pictured here as a set of billowing sheets that suggests nothing but, well, a set of billowing sheets. All that survives is Rice’s play, a still timely tragedy about a man who, after twenty-five years of service, expects a promotion, but who is instead fired and replaced by a machine and who kills his employer and finds moral redemption only after his death by execution. They should have done the play. The musical version is still awaiting production in Los Angeles.

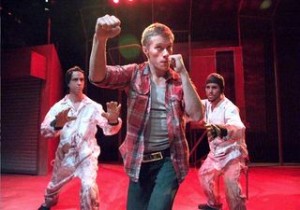

It becomes clearer, with each passing year and with each new production of The Cradle Will Rock, that the legend of the WPA project – under the direction of Orson Welles – being closed out of its Broadway opening and forced to open instead as a fiery political statement, with its actors speaking from the audience rather than on a stage, is perhaps greater than the show itself. It is hard not to feel the anger and the passion of its didacticism. And the marvelous caricatures of society types is agitprop theater at its most scabrous and potentially hilarious. Mark Blitzstein’s score, too, is quite extraordinary. But, in this hybrid production, the cradle stubbornly refuses to rock and even suggests that, though it should be as timely as today’s news, it is an artifact of the past. And, as delightful as

It becomes clearer, with each passing year and with each new production of The Cradle Will Rock, that the legend of the WPA project – under the direction of Orson Welles – being closed out of its Broadway opening and forced to open instead as a fiery political statement, with its actors speaking from the audience rather than on a stage, is perhaps greater than the show itself. It is hard not to feel the anger and the passion of its didacticism. And the marvelous caricatures of society types is agitprop theater at its most scabrous and potentially hilarious. Mark Blitzstein’s score, too, is quite extraordinary. But, in this hybrid production, the cradle stubbornly refuses to rock and even suggests that, though it should be as timely as today’s news, it is an artifact of the past. And, as delightful as  David O’s piano accompaniment is, the score cries out for richer arrangements. The satire is frenetic and blunted and in sharp contrast to the sober and controlled way Daniel Henning handles the musical’s more serious moments. The cast indulges in a mixed bag of theatrical styles. Only Jack Laufer registers with authentic credibility. And Lowe Taylor makes something vivid of Ella Hammer’s aria. Rex Smith brings a professionalism to the proceedings which one might say is almost too professional;

David O’s piano accompaniment is, the score cries out for richer arrangements. The satire is frenetic and blunted and in sharp contrast to the sober and controlled way Daniel Henning handles the musical’s more serious moments. The cast indulges in a mixed bag of theatrical styles. Only Jack Laufer registers with authentic credibility. And Lowe Taylor makes something vivid of Ella Hammer’s aria. Rex Smith brings a professionalism to the proceedings which one might say is almost too professional;  his labor organizer Larry Foreman seems to be in another show altogether and doesn’t even dress like anyone else in the cast, playing it as suavely as a Las Vegas performer might; the part requires a more aggressive raw-boned ferocity than Smith seems interested in projecting. One hopes that the 1994 production was superior. One hopes, in fact, that The Cradle Will Rock is better than its legendary status claims it is. At the moment, it remains open to argument.

his labor organizer Larry Foreman seems to be in another show altogether and doesn’t even dress like anyone else in the cast, playing it as suavely as a Las Vegas performer might; the part requires a more aggressive raw-boned ferocity than Smith seems interested in projecting. One hopes that the 1994 production was superior. One hopes, in fact, that The Cradle Will Rock is better than its legendary status claims it is. At the moment, it remains open to argument.

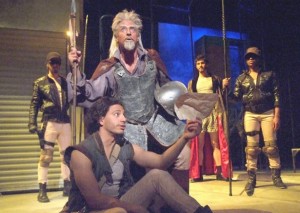

You can surely give credit to the Odyssey and the Blank and The Theatre@Boston Court for earnestly attempting difficult work, but they must be held responsible for not coming through. Boston Court, always depended on for first-rate work, has come a cropper with its tone-deaf production of Camino Real, the cry of pain from Tennessee Williams that has a notorious reputation, ever since it started out as Ten Blocks on the Camino Real, for almost never finding a director – not even the esteemed Elia Kazan could open the door to its secrets – who could get inside the soul of its author. Milton Katselas got close in a Mark Taper production a lifetime ago which had Williams himself memorably cackling throughout at his own delicious jokes.

You can surely give credit to the Odyssey and the Blank and The Theatre@Boston Court for earnestly attempting difficult work, but they must be held responsible for not coming through. Boston Court, always depended on for first-rate work, has come a cropper with its tone-deaf production of Camino Real, the cry of pain from Tennessee Williams that has a notorious reputation, ever since it started out as Ten Blocks on the Camino Real, for almost never finding a director – not even the esteemed Elia Kazan could open the door to its secrets – who could get inside the soul of its author. Milton Katselas got close in a Mark Taper production a lifetime ago which had Williams himself memorably cackling throughout at his own delicious jokes.

But this co-production with CalArts School of Theater does exactly what Michetti had suggested in his opening statement; it treats the play as if it were not the phantasmagoric and deeply personal masterpiece Williams created but rather as if it were a circus of decadence they came across in the unsolicited mail bin. If ever a play screamed out for a mature reading, with its literary allusions and its unswerving dedication to the desperation and loneliness of its motley crew of characters who have come to the end of an arduous emotional journey, it is this play. But what we get instead, in the directorial choices made by Jessica Kubzansky, is the callowness of youth plastered across the depth and complexity of Williams’s original design.

But this co-production with CalArts School of Theater does exactly what Michetti had suggested in his opening statement; it treats the play as if it were not the phantasmagoric and deeply personal masterpiece Williams created but rather as if it were a circus of decadence they came across in the unsolicited mail bin. If ever a play screamed out for a mature reading, with its literary allusions and its unswerving dedication to the desperation and loneliness of its motley crew of characters who have come to the end of an arduous emotional journey, it is this play. But what we get instead, in the directorial choices made by Jessica Kubzansky, is the callowness of youth plastered across the depth and complexity of Williams’s original design.

What makes it hard is the uncompromising poetry of the writing. Williams was a playwright and a poet; the poet in him always reached further and deeper than even his most poetic plays suggested. He may have been a better playwright than he was a poet, but poetry was in Williams like a constantly flowing stream from which sprang a fountain of pain and desire, both imagined and real. In what may be the most profoundly personal of all of the speeches ever written by Williams – Lord Byron’s despairing and oddly hopeful “Make voyages! Attempt them! There’s nothing else” – he has Byron say that “a poet’s vocation, which used to be my vocation, is to influence the heart in a gentler fashion….for what is the heart but a sort of – a sort of – instrument! – that translates noise into music, chaos into – order.” One cannot merely declaim these lines, as is so shallowly done here; one must know, in one’s own damaged heart, exactly what anguish and unspeakable joy exists within these words. We must hear the feelings, not just the poetry. But we must also hear the poetry. It is no easy task, to be sure, but it is precisely the task that insists upon being risked. You can’t fool around either with poetry or with matters of the heart.

What makes it hard is the uncompromising poetry of the writing. Williams was a playwright and a poet; the poet in him always reached further and deeper than even his most poetic plays suggested. He may have been a better playwright than he was a poet, but poetry was in Williams like a constantly flowing stream from which sprang a fountain of pain and desire, both imagined and real. In what may be the most profoundly personal of all of the speeches ever written by Williams – Lord Byron’s despairing and oddly hopeful “Make voyages! Attempt them! There’s nothing else” – he has Byron say that “a poet’s vocation, which used to be my vocation, is to influence the heart in a gentler fashion….for what is the heart but a sort of – a sort of – instrument! – that translates noise into music, chaos into – order.” One cannot merely declaim these lines, as is so shallowly done here; one must know, in one’s own damaged heart, exactly what anguish and unspeakable joy exists within these words. We must hear the feelings, not just the poetry. But we must also hear the poetry. It is no easy task, to be sure, but it is precisely the task that insists upon being risked. You can’t fool around either with poetry or with matters of the heart.

Kubzansky knows clearly who is being referenced in the characters of Marguerite Gautier (Dumas), Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (Cervantes), Esmeralda (Hugo), Baron de Charlus (Proust), Casanova, Byron and Kilroy, but she doesn’t get at all that Gutman is patterned on a character in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. And, given the description of him as a “lordly fat man,” it is also patterned on the actor – Sidney Greenstreet – who played him in the film version, so the casting of the trim and youthful Brian Tichnell in the part makes no sense at all (and neither does his pointless flash of nudity). Gutman should be a forbidding presence, not merely a presence. And when The Gypsy talks about her daughter Esmeralda, she says, “She watches television. She plays bebop. Reads “Screen Secrets.”” “Screen Secrets” is so evocative; it has been changed to “the tabloids” for no other reason than that it will be easier for a contemporary audience to understand. In a play that lives through its language, “the tabloids” is no substitute for “Screen Secrets.” In short, this Camino Real totally lacks the clarity and the depth of feeling that is a prerequisite for any production of the play.

Kubzansky knows clearly who is being referenced in the characters of Marguerite Gautier (Dumas), Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (Cervantes), Esmeralda (Hugo), Baron de Charlus (Proust), Casanova, Byron and Kilroy, but she doesn’t get at all that Gutman is patterned on a character in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. And, given the description of him as a “lordly fat man,” it is also patterned on the actor – Sidney Greenstreet – who played him in the film version, so the casting of the trim and youthful Brian Tichnell in the part makes no sense at all (and neither does his pointless flash of nudity). Gutman should be a forbidding presence, not merely a presence. And when The Gypsy talks about her daughter Esmeralda, she says, “She watches television. She plays bebop. Reads “Screen Secrets.”” “Screen Secrets” is so evocative; it has been changed to “the tabloids” for no other reason than that it will be easier for a contemporary audience to understand. In a play that lives through its language, “the tabloids” is no substitute for “Screen Secrets.” In short, this Camino Real totally lacks the clarity and the depth of feeling that is a prerequisite for any production of the play.  What it has instead is lots of senseless meandering and a total lack of focus, so that things just seem to happen haphazardly and incoherently. It does get better after the intermission, primarily because things generally quiet down, and because Marissa Chibas does manage to get beyond the surface of Marguerite Gautier and finds real meaning in her hard-earned recognition that “although we’ve wounded each other time and again – we stretch out hands to each other in the dark that we can’t escape from – we huddle together for some dim-communal comfort – and that’s what passes for love on this terminal stretch of the road that used to be royal.” And the scene between Kilroy and Esmeralda, when he attempts to lift her veil (does anybody need to be told what that is a metaphor for?), is a gem, because Matthew Goodrich and Kalean Ung play it simply, without adornment. And, finally, despite the brevity of his scenes, Lenny Van Dohlen brings genuine dignity to both his Don Quixote and his Baron de Charlus; in fact, his final moments as Quixote almost (but not quite) save this production from its worst excesses.

What it has instead is lots of senseless meandering and a total lack of focus, so that things just seem to happen haphazardly and incoherently. It does get better after the intermission, primarily because things generally quiet down, and because Marissa Chibas does manage to get beyond the surface of Marguerite Gautier and finds real meaning in her hard-earned recognition that “although we’ve wounded each other time and again – we stretch out hands to each other in the dark that we can’t escape from – we huddle together for some dim-communal comfort – and that’s what passes for love on this terminal stretch of the road that used to be royal.” And the scene between Kilroy and Esmeralda, when he attempts to lift her veil (does anybody need to be told what that is a metaphor for?), is a gem, because Matthew Goodrich and Kalean Ung play it simply, without adornment. And, finally, despite the brevity of his scenes, Lenny Van Dohlen brings genuine dignity to both his Don Quixote and his Baron de Charlus; in fact, his final moments as Quixote almost (but not quite) save this production from its worst excesses.

Women in Shorts is not, as promised, “fabulous.” These are six short plays by six different writers, directed by six different directors, with two actors, each playing six different characters, all on one set – two benches in a park. A more generic evening could not be imagined. The voices of the writers are not made distinct and not one of the directors seemed capable of getting one actor, Louise Davis, to do anything but make each and every character exactly and annoyingly alike. The other actor, Joanna Miles, was a bit nervous at the opening, but she was, at least, trying desperately to convey the sense of six different women. Unfortunately, she has nobody to play against for most of the evening. In the final play, Miles becomes, for a few brief shining moments, quite luminous, but it is a case of too-little-too-late. A fabulous time was not had by all.

Women in Shorts is not, as promised, “fabulous.” These are six short plays by six different writers, directed by six different directors, with two actors, each playing six different characters, all on one set – two benches in a park. A more generic evening could not be imagined. The voices of the writers are not made distinct and not one of the directors seemed capable of getting one actor, Louise Davis, to do anything but make each and every character exactly and annoyingly alike. The other actor, Joanna Miles, was a bit nervous at the opening, but she was, at least, trying desperately to convey the sense of six different women. Unfortunately, she has nobody to play against for most of the evening. In the final play, Miles becomes, for a few brief shining moments, quite luminous, but it is a case of too-little-too-late. A fabulous time was not had by all.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

Adding Machine: A Musical

photos by Enci and Ron Sossi

scheduled to close March 19 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.odysseytheatre.com/

The Cradle Will Rock

photos by Rick Baumgartner

scheduled to close March 20 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.theblank.com/

Camino Real

photos by Ed Krieger

scheduled to close March 13 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.bostoncourt.com/events/83/camino-real-by-tennessee-williams

Women in Shorts

photos by Ed Krieger

scheduled to close March 20 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/143986