LOVE CONQUERS COMMON SENSE

My takeaway about Oscar Wilde in David Hare’s intellectually stimulating but overly static play of ideas, The Judas Kiss, now at Boston Court, is this: The literary genius, raconteur and bon vivant was not the wisest of men, making him largely liable for his own downfall. It may have been that Wilde, a married man with children, was blinded by his desire for men, causing a profound lack of judgment. Or maybe the Pecksniffian mores of Victorian England had him so riled that he was out of touch with any instinct. During his ignominious trial for “gross indecency” as a homosexual, Wilde fairly did himself in, believing his wit, style and morals would make any argument for “pure love” melt a barrister’s heart (he even invoked Plato!). Instead, he was sentenced for two years of “hard labor” in prison, which set in motion his early demise. This 1998 two-act drama covers a few hours before and after he has served his jail term: Act I is at a London Hotel; Act II takes place in a Naples Villa. In both acts, the main character — other than Wilde — is Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, his lover. In trying to answer the mystery of why Wilde didn’t am-scray to France after his final trial, Hare delves into Wilde’s character and motives; the first third of the play is crammed with dramatics, but sadly it all goes downbeat from there. And besides Wilde, the characters are not well-drawn, particularly the despicable Bosie.

My takeaway about Oscar Wilde in David Hare’s intellectually stimulating but overly static play of ideas, The Judas Kiss, now at Boston Court, is this: The literary genius, raconteur and bon vivant was not the wisest of men, making him largely liable for his own downfall. It may have been that Wilde, a married man with children, was blinded by his desire for men, causing a profound lack of judgment. Or maybe the Pecksniffian mores of Victorian England had him so riled that he was out of touch with any instinct. During his ignominious trial for “gross indecency” as a homosexual, Wilde fairly did himself in, believing his wit, style and morals would make any argument for “pure love” melt a barrister’s heart (he even invoked Plato!). Instead, he was sentenced for two years of “hard labor” in prison, which set in motion his early demise. This 1998 two-act drama covers a few hours before and after he has served his jail term: Act I is at a London Hotel; Act II takes place in a Naples Villa. In both acts, the main character — other than Wilde — is Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, his lover. In trying to answer the mystery of why Wilde didn’t am-scray to France after his final trial, Hare delves into Wilde’s character and motives; the first third of the play is crammed with dramatics, but sadly it all goes downbeat from there. And besides Wilde, the characters are not well-drawn, particularly the despicable Bosie.

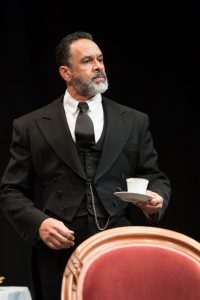

While there’s enough chewy, intelligent dialogue to earn our attention, the one thing truly bold about Michael Michetti’s bland and bemusing direction is the casting of Rob Nagle as Wilde considering Nagle was not born to play Wilde. Comedy was his forte many years ago, but recent turns with drama (and boy oh boy is Wilde ever dramatic in this play) have shown that Nagle is consistently growing. This is his magnum opus. More than ever, Nagle is performing de profundis, offering breathtaking emotionality. This is even more extraordinary given that Wilde, famous for his magnetic individuality long before his professional success, had adopted the pose of an effete young man (“Effeminate, but [with the] vitality of twenty men,” Max Beerbohm wrote), yet the only true affectation by Nagle is an Oxford accent. We don’t even get an inner wag.

Anyway, we’re not watching Oscar of reality, really (indeed, the playwright suggests that he’s “not at all the languid pansy of legend”). While Nagle meets Wilde’s height of 6’3″, he is hardly as some noted “fat and greasy” or “particularly revolting” (Bosie wrote, “There is no charm in his elephantine body”). This Oscar looks quite fit. Which makes it strange that Nagle as Wilde looks almost exactly the same after  prison as he did before (another directing befuddlement — no fat suit in the first act?). Mr. Hare has Wilde so determinedly indecisive, inactive and indulging in self-pity (all of which were said to be true), that I found myself missing other sides of him.

prison as he did before (another directing befuddlement — no fat suit in the first act?). Mr. Hare has Wilde so determinedly indecisive, inactive and indulging in self-pity (all of which were said to be true), that I found myself missing other sides of him.

When you know the details of such a juicy story, it’s a wonder that we don’t get a more rounded depiction of Wilde by Hare. Wilde was a torn man: perversely paradoxical, sardonically aesthetic, and (necessarily) obsessed with concealment. In his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, first published in 1890 — ten years before the author’s death in exile — Wilde would both embrace and attack decadence and depravity. Up until the melodramatic ending, he was enthralled with his title character: a perfect pretty boy who radiates youthful innocence, despite a career of callous crimes. We all know what happens: 20-year-old Dorian never ages while his portrait turns toxic.

How prescient was the Irish-born scribe. One year later in 1891, Wilde would meet and fall in love/lust with Bosie. 16 years his junior, this Adonis-like 22-year-old Oxford undergrad and talented poet would come to be the author’s own Dorian Gray — his literary muse, his evil genius, his restless lover. It was during the course of their affair that Wilde wrote Salomé and the four great plays which have cemented his legacy. But it was his near obsessive/compulsive love for Bosie that would be his  undoing. To say that their affair was tempestuous is an understatement, but Wilde was addicted. This play skirts around their squabbles, which must have been Albee-esque in nature. And the trial, which ended shortly before Act I, is fought about between Bosie and Robbie Ross, Wilde’s ardent friend, first male lover and future literary executor — not between Wilde and Bosie.

undoing. To say that their affair was tempestuous is an understatement, but Wilde was addicted. This play skirts around their squabbles, which must have been Albee-esque in nature. And the trial, which ended shortly before Act I, is fought about between Bosie and Robbie Ross, Wilde’s ardent friend, first male lover and future literary executor — not between Wilde and Bosie.

Ah, yes, the trial. In 1895, at the height of his literary success, with The Importance of Being Earnest playing to acclaim, Wilde had Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, prosecuted for libel (the Marquess left a calling card for all to see calling Wilde a “somdomite” [sic]). But the evidence unearthed during the trial led to Wilde’s own arrest on charges of “gross indecency” with members of the same sex. Two more trials followed, after which he was convicted. (Using quotes from the trial and other sources, Moisés Kaufman created the fascinating 1997 play, Gross Indecency.)

In 1897, following his served sentence, Wilde moved to Naples, Italy, where Bosie had arranged a Villa. After three months and much local scandal, Bosie returned to family (and the money that the entails entailed); Wilde left Naples in February 1898 and went to Paris, where he died destitute at 47 in 1900.

In 1897, following his served sentence, Wilde moved to Naples, Italy, where Bosie had arranged a Villa. After three months and much local scandal, Bosie returned to family (and the money that the entails entailed); Wilde left Naples in February 1898 and went to Paris, where he died destitute at 47 in 1900.

Given that intrigue, it’s sad that Hare was only interested in what could possibly have motivated Wilde to be the architect of his own undoing during the trial — and why he took an afternoon repast instead of getting the hell out of Dodge. It seems Wilde has simply given up a fight, which doesn’t create an opportunity for heartbreak and makes the play too passive. Judas Kiss has rarely been produced since it was first seen 20 years ago, and since the L.A. premiere didn’t happen at the Taper, Geffen, SCR or the like, you can be assured it’s a problematic play. While creating some moments of terrific intimacy, Mr. Michetti fails to make the play less stagnant than written; indeed, the blocking overall is rather flat, the urgency tacit, with Wilde seated for almost the entire second act.

And then there’s the casting issues:

While Ross was openly gay, it’s strangely not part of his character here, which is written as rather somber. In Act I, he evenhandedly urges Oscar to leave the country at once before the police arrive to arrest him. In Act II, he evenhandedly urges Oscar to leave both Naples and Bosie. Why does Darius De La Cruz act one-note and diplomatic, almost like a secretary? Why is he so damned calm as everyone ignores his advice?

And why would so gargantuan a life-force as Wilde spend two minutes with Colin Bates’s Bosie, an arrogant, loud and whiny social climber who makes Wilde’s irrational affection seem simply silly. Bates matches the physicality perfectly (he is unclothed in Act II), but missing is his appeal and sexual self-assurance. As such, I never felt the connection between the poets.

And why does the naked hunky Italian fisherman that Bosie just shagged in Italy look and sound more like an Asian call boy in Amsterdam’s Red Light District?

And why is it only Mr. Nagle whose every word could be understood throughout — in a 99-seat house?

The staff at the hotel is a winning combination: Will Dixon, sturdy and accommodating as the Scottish head butler, Moffatt; Mara Klein, winsome and winning as a not-so-servile cockney maid, Phoebe; and Matthew Campbell Dowling as Arthur, the valet into dalliance and delivering. Dowling exudes servitude but lacks the sexual je ne sais quoi of this insatiable lad (the hotel scene begins with valet diddling maid, both fully naked). Everybody in the room is an underground gay or bisexual (who knows about Phoebe?), but strangely that doesn’t seem to inform how they relate.

Ironically missing from the play, even with the use of Wilde’s staggeringly clever bons mots, is humor. It’s odd that with a script that parades a daunting sum of compacted ripostes and aphoristic skill, everything is so damned serious and solemn. There are plenty of amusing lines, but we have more of Wilde’s aversion to the narrow models of Victorian British upper-class behavior and less humor about it. While his situation here is far from the tenuous duplicity in The Importance of Being Earnest, Judas Kiss suffers from a shocking lack of — quoting his friend George Bernard Shaw — Wilde’s “irrepressibly witty personality.” We could have used wittier direction to balance the often-dreary situations.

Boston Court is usually known for stage design, but this is peculiar, looking like a full-on workshop production. During Act I at The Cadogan Hotel, there is a giant upstage black-curtain backdrop, and light trees clearly in view of the audience on both sides of the stage, as if they were inside the hotel room. The door to the bathroom opens to black drapes and flats. The stage is floodlit by David Hernandez for most of the act with little shading. Yet strangely the stage left doorway opens to a barely visible but exquisitely detailed hotel hallway – replete with sconces, carved wooden walls, and beautiful carpeting (which couldn’t be seen from house right). Just as plummy are Dianne K. Graebner’s gorgeous Victorian outfits, Courtney Lynne Dusenberry’s authentic props, and set designer Se Hyun Oh’s fancy furniture and Oriental rug.

In the second act at Villa Giudice in Naples, we still have trappings indicative of the period, albeit more bare-boned as Wilde is now penurious, but the backdrop is a large, rectangular, white, blank canvas. The hallway to the kitchen is now unadorned, but the hallway from the Villa’s front door is gorgeous floor-to-ceiling texture and color.

If this is to say that Wilde’s life was always on stage, away from reality, it’s a clever choice (the Irish expat says, “I am cast in a role. My story has already been written”). Unfortunately, it doesn’t gibe to have the stage exits and props highly detailed (the luxurious lobster that Wilde lunches on had me licking my lips) but not the backdrops, which makes it seem less an artistic decision and more a cost-cutting one.

If this is to say that Wilde’s life was always on stage, away from reality, it’s a clever choice (the Irish expat says, “I am cast in a role. My story has already been written”). Unfortunately, it doesn’t gibe to have the stage exits and props highly detailed (the luxurious lobster that Wilde lunches on had me licking my lips) but not the backdrops, which makes it seem less an artistic decision and more a cost-cutting one.

On October 1, 1897, Oscar Wilde wrote to his publisher,”[Bosie] understands me and my art, and loves both. I hope never to be separated from him. He is a most delicate and exquisite poet, besides — far the finest of all the young poets in England. You have got to publish his next volume; it is full of lovely lyrics, flute-music and moon-music, and sonnets in ivory and gold. He is witty, graceful, lovely to look at, lovable to be with. He has also ruined my life, so I can’t help loving him — it is the only thing to do.” Hare suggests not wrongly that beauty — as Wilde would have it — triumphs over all, but watching a remarkable mythical individual make unremarkable human choices doesn’t make for remarkable theater — at least not in this production.

photos by Jenny Graham

The Judas Kiss

Boston Court Performing Arts Center

70 N. Mentor Ave. in Pasadena

Thurs-Sat at 8; Sun at 2

ends on March 24, 209

for tickets, call 626.683.6801 or visit Boston Court

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

You are a brilliant writer. That is all.